Unpublished.

.

I first met Ann Shelton at Wellington City Art Gallery in 1992. I was there with artist Giovanni Intra, installing his Blood Mobile in the new-artists show Shadow of Style.1 They were chums. Shelton was a press photographer. She was working at the Dominion Post to pay the bills and documenting the lives and times of local glue sniffers in serious black-and-white in her spare time—working towards a show.2 But Auckland and art school were calling.

In 1993, she quit her day job, moved to the big smoke, and embarked on a BFA at Elam. In Auckland, Shelton and Intra became an item. They lived in a flat in Grafton, where he wrote his MFA dissertation, ‘Subculture: Bataille, Big Toe, Dead Doll’. But, Karangahape Road would become the centre of their universe. K Road was the old red-light district—a magnet for drag queens, loafers, and party animals, as well as people with real problems. Shelton wined and dined at Verona, partied at the Staircase, and hung out at Teststrip, the artist-run space operated by Intra and Co., which relocated to K Road.3 Shelton herself soon moved into a flat above a K Road butcher’s shop, where she lived with her girlfriend, photographer Fiona Amundsen.

Via stints recording the gay/queer scene and surveying public-toilet graffiti, Shelton’s focus shifted from documenting Others (those Wellington ‘street adults’) to documenting her self, her friends, and their hectic party life. In 1995, she embarked on the work that would become her 1997 photobook Redeye. This ‘diary’, as she called it, features a selection of sixty-four photographs in which she immortalises her fellow artists and flatmates, friends and lovers; her home, haunts, and hobbies.4 A time capsule, it now seems to sum up the K Road ethos, standing in for that milieu and moment.

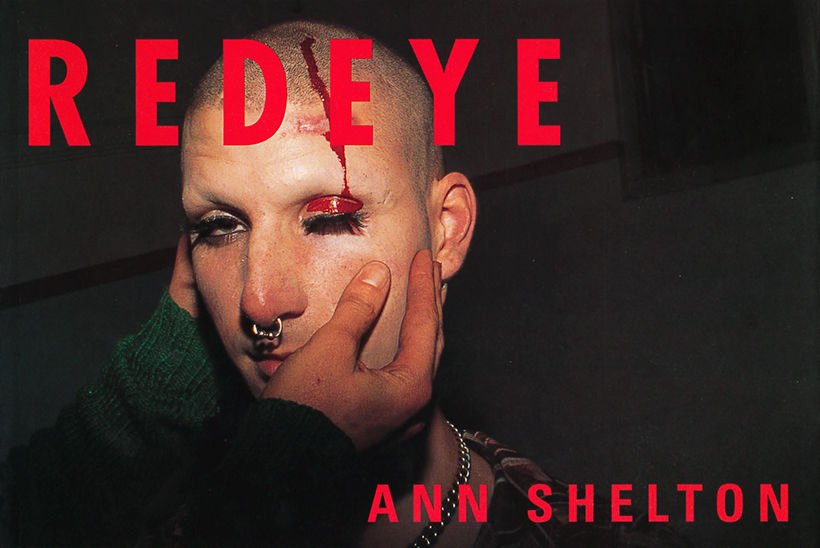

The Redeye photos are snapshots—intimate, tightly cropped, in your face. They were made on slide film using a plastic Olympus camera. Shelton favoured the flash, guaranteeing a flat, gaudy, saturated-colour look. The book’s title refers, in part, to the red, strung-out, alien-eyes effect produced by such cheap cameras, where the flash is located too close to the lens. The book offers numerous examples.5 Flicking through it feels like ploughing through a shoebox of disordered snaps, where characters turn up repeatedly in different hairdos and outfits. It would feel rather different if it was published now, in our age of selfies and Instagram, when we are used to people making their private snaps available to the world.

Shelton’s crew fancied themselves Warholesque superstars and flaming creatures, walking on the wild side. In the book, punk collagist Ava Seymour appears often, looking absolutely fabulous. With big hair and eyelashes, in a boa or body-hugging leopard skin (or with an inflatable sex doll), she’s Tura Satana, Vampira, and Poison Ivy, Peg Bundy and Divine, rolled into one. She dresses like a man in drag, exaggerating her femaleness, as though her gender did not go without saying. By contrast, her gender-bending partner, Kim Elizabeth ‘Swampy’ Swanson—singer in garage-punk band Bandy Candy and the Cocksuckers—passes as a he. In one image, dressed as a bloke, she lights a fag and manspreads, resting a brown beer bottle between her legs. In another, she wears a t-shirt explaining ‘penis’, while sculling a Heineken. Ironic feminism!

Girls will be boys and boys will be girls, and everything in between. The drag queen Booby Tuesday also appears repeatedly. In one shot, he’s getting ready, half dressed, wigless, falsies hanging out. In another, transformation complete, he proffers his mini-skirted arse in front of a sign that explains ‘After Hours Enquiries’ and lists a phone number. Artist Joyce Campbell is also shown in an unladylike pose, albeit in flattering black Lycra, in the ring, flipping fellow girl-wrestler La Rissa, in red Lycra—very Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! Meanwhile, artist David Scott effects a limp wrist.

It was a queer old world. Artist David Townsend appears excessively attired, in white face paint with bright red lips, like a geisha. He looks like a younger incarnation of the Mystery Man from David Lynch’s Lost Highway, which hadn’t come out yet. In another shot, he is filthy, making a devil-horns gesture, smeared in his own blood, having earlier taken to his shaven head with a staple gun as part of a look-at-me masochistic performance at the Ambassador Theatre, Point Chev.—artist Peter Roche’s place. Remembered for his self-harm performances in the 1970s, Roche is the subject of another image, trashing an armful of live fluoro tubes during a performance at Teststrip.

Not everyone was an extremist. Actually, an odd cast was caught in Shelton’s net. There’s Amundsen (now famed for her conceptual photography). The shot of her with her pants around her ankles, perhaps passed out, seems improbable—she always seemed too demure, too serious. And there’s video artist Lisa Reihana (whose work Native Portraits would become a Te Papa favourite) and photographer Haru Sameshima (as Rim Books, Redeye’s publisher), both made up for a Monica magazine photo shoot.6

There are shots of art works that don’t look like art works, because only bits are shown or we can’t see the context. The glowing circuit boards are part of a Roche sculpture. The shiny panels are not disco or hairdresser decor but a Denise Kum installation at Auckland Art Gallery’s New Gallery. The ‘Super Stormy’ sign is a work by Michael Stevenson at Teststrip and the missing louver windows are part of a work by then-emerging Dion Workman at 23a Gallery. Also, peppered amongst the racy and risqué images are banal, obscure ones: an anonymous glazed K Road office building, a nondescript corridor, red PO boxes, and a random detail from a mural. Not to mention ‘crime-scene’ images: marker-pen graffiti on a car, vomit in a urinal, and sauna showers. We can only suspect that—to those in the know—these images are radioactive with happy memories. Meaningful, if you were there; meaningless, if you weren’t. Or, perhaps the point is: you weren’t there.

Designwise, Redeye stood out. Designer Bepen Bhana opted for glossy stock and a distinctive A5 landscape format; any portrait-format shots were simply run sideways. Shelton’s lurid images were bled—no aesthetic white space—and text pages were printed on green! There was no explanatory essay. The captions were consolidated on a single page at the back, like an index, making it a chore to consult them, especially as only some pages were numbered. They were little help. As Shelton admitted, they ‘don’t really tell you very much’.7 There was no real order to the images, but there were telling juxtapositions: a Seymour sculpture (a plucked, headless chook, wearing a pearl necklace, with a red apple stuffed up its bum) faced off against Seymour herself (dressed in red).

Redeye was indulgent. As much as Shelton embraced a transitory, ‘live fast, die young’ lifestyle, she also believed it should be preserved for posterity. She thought Intra’s cocaine ring, Amundsen’s sneakers, and her own new tattoo were too good to not share with the world. Her subjects agreed. With Redeye, they invest—and ask us to invest—in their mythologisation. It’s this insistent narcissism that makes Redeye work.

Redeye didn’t come out of the blue. In the 1990s, queer and raunch culture were becoming mainstream. By 1992, Madonna had already published her photobook Sex. Redeye also grew out of a tradition of gay-scene photography identified with photographers like Robert Mapplethorpe and Peter Hujar. And it was indebted to notorious photobooks where participant photographers could be as badly behaved as their subjects: Larry Clark’s Tulsa (1971), Nobuyoshi Araki’s Tokyo Lucky Hole (1985), and Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1986).8 Indeed, Shelton was routinely cast as New Zealand’s Goldin, albeit a decade or so after the fact.

There were also precedents in New Zealand photography. Shelton looked back to Fiona Clark’s 1970s tranny-scene documentary work. With her raunchy subject matter, she also was an heir to the risqué late 1980s/early 1990s work of Fiona Pardington and Christine Webster. But, though they messed with sex-and-gender codes, Pardington and Webster dispensed with the documentary assumptions of Clark’s straight photography (they wanted their photography to be as ‘bent’ as their sex). In this context, Redeye was not forward looking, but rather retro, bucking the trend for constructed photography, reasserting photography’s documentary authenticity.9

When Redeye came out, it confused me. It made me feel like an insider and an outsider. True, it starred people I knew and worked with, but they were not really my people. They were younger than me and too cool for school—they treated me like ‘the establishment’.10 And, though we launched Redeye at Artspace (also on K Road) when I was boss (showing the work for a mere three days!), and though I figure as a pointless blob in the back of one shot (with blue-chip abstractionist Stephen Bambury, of all people), whenever I look at the book, I’m reminded that I was never in the club. The craziness only happened after I left the room; I heard about it the next day. My sense of exclusion was only made more acute by being so close to Redeye’s generational envelope and psychogeography.

Shelton says Abigail Solomon-Godeau’s essay ‘Inside/Out’ was a big influence on Redeye.11 The essay contrasts Goldin’s and Diane Arbus’s approaches. Both photographers document marginals, but Arbus’s treats hers as strangers, as others, while Goldin’s are her and her friends. Arbus is voyeuristic and brutal (an outsider approach) while Goldin is empathetic and implicated (an insider one). While Arbus photographed queers disdainfully, Goldin captured them touchingly. But, as Solomon-Godeau also observes, inside and out are never so clear and distinct. Certainly, Shelton did not simply view her cohort from within, but was already imagining them and herself viewed from outside, by others. And that’s how they all saw themselves. They wanted to be freaks. They were the camera-ready underground.

This inside-and-out ethos informed the art of the two Teststrip principals that feature most prominently in the book, artists Daniel Malone and Giovanni Intra. At the height of post-colonialism, Malone mimicked Others. For a while, this merry prankster sported an Afro and a Fu Manchu moustache. He claimed Cherokee whakapapa, and slummed it as a tagger and as a rapper (with the plaintive battle cry ‘Me Tu’).12 In Redeye, he is drunkenly boxing himself around the head in a Teststrip performance (he could have been a contender!), clamping his tongue between chopsticks, and answering the phone in an Asian t-shirt, a butcher’s apron, and a hard hat—ever performing, ready for his close-up.

Born in 1968, Intra missed out on the Paris riots and punk. He explored subculture, but belatedly, at a distance. This can be felt in the Redeye preview he wrote for Pavement in 1996. It sums up the book by what it says and by how it says it, switching from complicit boosterism to critical disdain without slowing to change gear. While issuing his racy, conflicted verdict, Intra fails to disclose his insider status—that he was one of the book’s key subjects and had been Shelton’s lover.

He writes: ‘Shelton’s new book is part fashion, part accident and part sheer embarrassment. Her idiosyncratic version of the photographic portrait hones in on the people of a nonsensical culture of “experimentalism”, an excessive yet mannered avant-garde of gender-bending, faux glam and self-mutilation which chokes on foundation whilst desperately trying to swallow art theory … What Shelton modestly terms a “social diary” is really a charismatic expose of the hideous truths and self-conscious mythologies of unemployed psychopaths who frequent Verona cafe and actually believe in drag.’13

Intra’s text highlights the key question: who is Redeye addressed to—insiders or outsiders, sympathetic participants or judgemental voyeurs? Or, does it speak to both, but differently?14

Times change. Redeye was twenty years ago. Intra said its images ‘envision a population we know is condemned to obscurity, not to mention old age, premature death and a whole host of attendant mediocrities’. Where are they now? Intra headed to LA, became an influential art critic and gallerist, but crashed and burned—dead at 34, an overdose in 2002. Malone is living in Poland, where he’s the consummate insider-outsider. As a proofreader, he helps the Polish art world with its English. Seymour abandoned the punk edge of her collage work, for a more genteel formalism. Townsend is in London, working for the upmarket interior decorators Atelier, who cater for the elite with their ‘precision designed and expertly crafted residences’. Etcetera. But at least one Redeye superstar is still hanging out on K Road, living the dream. Swampy’s current band is the Blue Bloods. They just made a clip for their song ‘Slut on Junk’.

Sadly, it’s hard to sustain rebel status—unless you die. After Redeye, Shelton’s work shifted. She walked away from documenting subcultural pranks and took a cooler, conceptual approach, accompanied by a production upgrade. Her new direction would find itself perfectly tuned to emerging university-research agendas. Now she’s Associate Professor Shelton, living, with her graphic-designer husband Duncan Munro, in a vintage architect-designed modernist house in Wellington’s Wilton—a world away from K Road.

The house has just been the focus of a cover story in Home magazine, and Shelton’s A Spoonful of Sugar (2015)—another Rim book—spruiks it. Location, location. Everything changes, but some things never do. In Spoonful, as in Redeye, Shelton crossbrands. She entwines her pedigree with other people’s. The book associates her, as the proud new home owner, with the house’s emigre Jewish architect Fredrick Ost (who escaped the Nazis) and his client, spinster Nancy Martin (‘purportedly the first single woman in Wellington to receive a mortgage to build her own home, a trail-blazing woman … responsible for bringing … the recorder to New Zealand’). The recorder … bless! What happened to the glue sniffers and queers?

Shelton explains: ‘Dipping into and out of these narratives, this project seeks to invoke the ghosts of change and of futures—of feminism, of modernism, of a haunted house, a musical house, a diasporic house, a Jewish house, and a house from Aotearoa, thereby making visible and audible links between banking history, gender politics, agency and the role of a woman in architecture in Aotearoa.’15

Shelton has moved up in the world, and Spoonful can be read as an update and antidote to Redeye. And yet, flicking through its impeccably exposed lifestyle interiors, we find—in the salon hang, on those original orange-pegboard walls—works from Shelton’s old Redeye friends Intra and Seymour. These souvenirs of another life linger like pinned butterflies, wormholes to another space and time, misty watercolour memories of the way we were.16

- I curated Shadow of Style with Greg Burke. It was a joint project between Wellington City Art Gallery and the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth, where I was curator.

- This work was presented in her 1993 show Don’t Push Me/Kaua au e Puhingia [Puhinga]: Photographs of Street Adults at Lower Hutt’s Dowse Art Museum.

- Teststrip is sometimes considered New Zealand’s first artist-run space. It was certainly the first space of its kind. Founded by artists—including Merylyn Tweedie, Giovanni Intra, Daniel Malone, and Denise Kum—it opened in Vulcan Lane, Auckland, in 1992 and moved to K Road in 1994, where it ran until it ran out of steam in 1997. Shelton documented its demise, photographing a black shroud covering the Teststrip sign, so it read RIP.

- All but six were shot in Auckland. Three were shot in Wellington, and one each in Mangawhai Heads, Timaru, and Tokyo.

- The cover image—of David Townsend bleeding from his forehead into his eye—frames Shelton’s title as an affront to vision, like the eye-slicing shot in Un Chien Andalou (1929). Here’s blood in your eye.

- ‘Shooting Gallery’, Monica, Summer 1997: 47–50. Styled by Kirsty Cameron and shot by David Scott at Artspace. Among others, it featured artists David Townsend, Lisa Reihana, Ann Shelton, and Haru Sameshima.

- Lava, no. 24, 13–24 August 1997: 16.

- Shelton interviewed Larry Clark for Pavement after he released his film Kids. ‘Teenage Lust’, Pavement, February–March 1996: 66–70. Intra provided the intro.

- Clark and Pardington both featured in One Hundred and Fifty Ways of Loving, the pornography-statement show Shelton co-curated with Paul Booth and Kirsty Cameron for Auckland’s Artspace in 1994.

- Admittedly, I was living in Dunedin for most of the Redeye period. Then again, so was Danny Butt, who, in his Teststrip eulogy, writes: ‘The minutes of [Teststrip board] meetings from this time make hilarious reading—strategies included “Send invites to the powers that be to let them know that they are not invited—Leuthart, Burke, Leonard, Killeen (because he always comes)”.’ ‘TeststRIP’, Log Illustrated, no. 4, Winter 1998: 6.

- Inside/Out’, in Public Information: Desire, Disaster, Document (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1994), 49–61.

- See Giovanni Intra, ‘Daniel Malone: Triple Negative’, Art and Text, no. 70, 2000: 42–3.

- ‘Drive-By Shootings’, Pavement, no. 10, 1996: 10.

- Interestingly, Redeye did enjoy some cachet offshore. Heroic enlargements of Redeye images were installed in the Glasgow nightclub, the Arches, for Fotofeis, in 1997, and a second edition of the book was published by Dewi Lewis, in Stockport, enabling international distribution. The online Photo-Eye Bookstore still mistakenly lists the book as ‘a riveting portrait of British punky pop culture’. www.photoeye.com/bookstore/citation.cfm?catalog=PK471&i=&i2=.

- www.rimbooks.com/wordpress/a-spoonful-of-sugar.

- On 5 and 6 December 2015, Shelton staged House Work, an ‘open home’ for Enjoy’s project Enjoy Feminisms. She displayed her new house stripped bare, but for her art collection. Visitors heard a Pip Adam story narrated from a hidden speaker. ‘Abigail was out walking because she was fat …’ An earlier Shelton project, Abigail’s Party (1999), was a set of brag pictures of her cool K Road apartment. That project took its name from the 1977 Mike Leigh stage-and-television play.