Midwest, no. 10, 1996.

I stumbled upon the work of Edgar Roy ‘Chook’ Brewster on an unscheduled visit to Taranaki Aviation Transport and Technology Museum, in New Plymouth. There, I found the remains of an aeroplane’s wing and a chunk of its tail, tables, chairs, bits of a house, boxes, strange publications, models, beehives, knick-knacks. These odd things had one thing in common—all were constructed upon hexagonal principles. Handwritten labels framed up the remnants as part of an imaginative experiment in engineering and design, promoting their creator as a visionary, the pioneer of Norian philosophy and Norian construction methods.

.

For thirty years my life has been that of a commercial beekeeper … Beekeepers usually suffer many stings in the course of a day’s work and it is likely that my share has been at least one quarter of a million. Each bee sting is a severe shock. The result of thousands of stings and the pain thereby suffered cause a thoroughly shocked condition and a tremendous intensity in which one vibrates at a higher rate than normal. The mind grows very alert, but the speech often becomes poor. Beestings sharpen the wits at the expense of the speech … The result of such stimulation is that one becomes impelled to attempt the most difficult tasks, with inspiration always close at hand. Another is that one acts like a bee, thinks like a bee and becomes hexagon minded, thus the right angle is no longer acceptable.1

.

In 1927, aged 21, Brewster embarked on a life-long career as a beekeeper. He could hardly have known how decisive this would prove. Tending his hives, Brewster became obsessed with the hexagonal logic of the honeycomb, reconciling, as it did, the polygon with the circle, the straight line with the curve. Communing with the bees, it came to him that the right angle is against the will of god. ‘Where in nature’, he asked, ‘does one find right angles?’ Not simply a matter of convenience, a principle for bees alone, Brewster saw in the honeycomb a message from God, instructing men how to live. The bees were setting a good example. This revelation would be the seed of Brewster’s Norian (short for NO RIght ANgles) philosophy. The hexagon became an imperative: both practical and pious.

.

The world is round. Why, then, does man try to do everything in it square? By no example does Nature show man how to use the right angle and its product the square. So that man has no authority from Nature for his perpetual use of the harsh square with its ugly right angles and aggressive sides set rigidly opposed to each other at the cruellest angle. The right angle, then, is the evidence of man’s self-determination and the product of the exercise of his free will with not a thought of anything but himself. Thereby he proves his immaturity. Look around at the loveliness of Nature and see how every prospect pleases, and only man is square … Surely man is but a square peg in a round world. Surely square-minded man is the worst of all possible misfits in this circular world of ours.2

.

Brewster had all sorts of theories. An amateur aviator, he thought he could build a revolutionary aeroplane which would achieve its lift using power rather than speed, ‘like a quail’. From around 1937 to 1940, he tested his idea using models. He proceeded to obtain a US patent for his ‘airfoil lift co-efficient varying means’. Though he was convinced of the merit of his ‘theory of flight’—which he elaborated in a text he said took two days to read—others weren’t so sure. Brewster had no special training in this field and, to those in the know, his ideas appeared to be a mixture of the self-evident and the far-fetched. Brewster tried to enlist support from various sectors—government departments, corporations, private individuals—with little success. The authorities saw nothing new or valuable in his ideas. Not defeated, Brewster began the construction of a full-size prototype. In building the plane’s wing, he drew inspiration from his beloved bees, developing a method of honeycomb bracing. Sadly, the aeroplane project was brought to a halt in 1941, when Brewster’s wife died, leaving him with six children to raise. Brewster was forced to break away from his labours of love and to redirect his energies for a while.

.

To progress spiritually, man must know and glorify God. In his construction man can glorify God only in the ways shown to us in Nature, and those are entirely circular ways. God is not anything that is contradictory. God does everything with circles and has nothing to do with squares … That is why man has lost contact with God and increasingly so since the advent of the machine age over the last century, resulting in a very square age.3

.

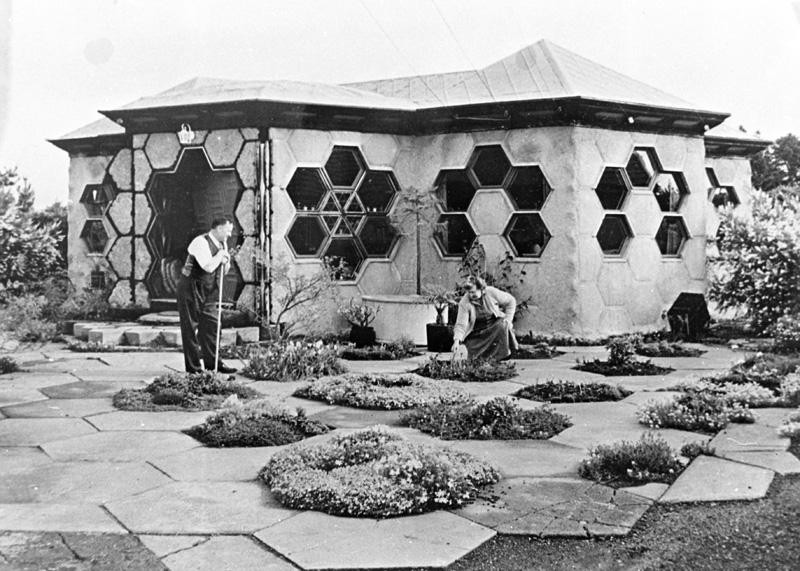

Apparently, it was in constructing the wing for his experimental plane that it first dawned upon Brewster that a hexagonal system might be the best way to build a house. In 1947, he remarried, and, by 1949, it was possible for him to again devote time to experiments. He started working on a model home, hexagonal in design and supposedly free of right angles—a prototype for general manufacture. It would have a hexagonal floor plan—six hexagonal rooms off a hexagonal central room. It would come prefabricated in standard units: hexagonal parquet wall panels, hexagonal floor panels, hexagonal windows. Ceilings would be triangulated, as would sub-floor and sub-wall framings. In 1953, Brewster assembled the house in just ten weeks at 36B Sanders Avenue, New Plymouth. Finishing touches included hexagonal paving stones and a hexagonal letterbox. ‘This house is being built to develop and perfect geometric methods of construction, of prefabricating housing upon a triangular basis of construction which appears to be more suitable for that purpose than present square methods’, Brewster explained. But was it so suitable? Insisting on hexagons may have necessitated a novel and magnificent building, but it meant there were all sorts of extra problems to solve. While the hinged modular doorways were ingenious, they were also impractical and fussy.

The Hexagon House immediately attracted attention from the local community, then throughout the country, and soon even as far away as the US and Britain. On fine days, the doors were left open and people were free to wander though. Brewster and his second wife Nettie entertained visitors, performing songs they composed jointly. Their repertoire included ‘Lovely Egmont’ and ‘The Beekeeper’s Song’. Mr Brewster loved talking to visitors, preaching and perfecting his philosophy of avoiding right angles. There was no charge, but visitors were encouraged to buy the Brewsters’s honey and their sheet music. ‘All we ask is that you come with an open mind ready to receive such measure of Truth as it has become our lot to offer’, he explained.

.

All the soft loving thoughts of the world are expressed in circular ways. The 120-degree angle of the hexagon is the soft answer to any problem. All the hard, unkind thoughts of the world are expressed on the square. The right angle is the hard answer that incurreth wrath. Jesus Christ taught us to love one another, even to love our enemies. Love is commonly symbolised as a halo. The rejection of love was the Cross with twelve right angles. The Nazis, too, symbolised their ideas of might and power, truly Godless thinking, by their Swastika, which has twenty right angles. Always the right angle will stand for Godlessness and the circle for God-consciousness.4

.

Brewster may have rejected the twenty right angles of the swastika but, for all the talk of love, he was something of a totalitarian himself. He wanted every little thing to conform. The house was a total concept. There was hexagonal furniture: tables and chairs. There were hexagonal carpets and a hexagonal patchwork quilt for the bed. Correcting Leonardo da Vinci, Brewster trimmed the corners off a print of the Mona Lisa and hung it in a hexagonal frame. In 1957, the house was celebrated in a self-published ‘souvenir’ booklet, with hexagonal pages, whose numbered text blocks had to be read clockwise. The cover even featured a hexagonal typeface. Everything Brewster did was hexagonal. He put his honey in tins with hexagonal patterns on the labels, and packed the tins in hexagonal boxes for good measure. He wrote hexagonal letters and put them in hexagonal envelopes. For Brewster, one shape fitted all; there was one solution to all problems. The hexagon was a divine template. So simple—God’s will and practical too.

.

Quite adequately one can express love as a circular theme. One realises that no matter how big it is, a curve must eventually result in a complete circle. God is complete. The idea of a straight line or two parallel straight lines stretching on to utter infinity is not acceptable to a world of love and completeness. Attraction (Love) must be a curve or circular theme. Rejection (Hate) can be expressed and understood as a straight line or as a right angle.5

.

The Hexagon House featured in newsreels. Articles appeared in Popular Mechanics and elsewhere. There were postcards. But despite the house’s popularity, it was accepted more as a curiosity than as a new university. Norian philosophy never captured the popular imagination. And yet, while Brewster was a crank, an eccentric, he was a valued one. He wasn’t off the map, simply a side-show. The 250,000 people who reputedly visited between 1953 and 1974 included Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

.

I suspect that the year 2000 will see laws in existence against the right angle, making it an offence, a very serious offence against the public health, with considerable penalties against its use.6

.

Brewster seems to have had something in common with Buckminster Fuller, the American engineer-architect-visionary who gave us the geodesic dome. (Back in the late 1920s, Fuller had already developed a super-light ‘dymaxion’ hexagonal house, with its roof and floor suspended from a central mast.) Both men combined a utopian vision of the future with a desire for practicality and a faith in their own brands of geometric idealism. Both were interested in prefabrication and abhorred traditional building logics. Both cultivated maverick status. Interestingly, there is no evidence that Brewster knew of Fuller’s work—he seems to have developed his plans in the splendid isolation of Taranaki. Certainly, Fuller’s thinking was more thorough from an engineering point of view. While Brewster argued that his house didn’t contain any right angles, clearly it did. Floors and walls may have been made of hexagon and part hexagon sections, but the walls were perpendicular to the floor and all the materials he used were derived from rectangular blocks and sheets. Brewster’s construction methods were less radical than he argued and far less practical than he claimed. The hexagons were really more a decorative motif than a new structural principle. However, in other ways Brewster was far more radical than Fuller. As we will see, he was on the verge of understanding the hexagon as a key to absolutely everything.

.

Everything that the bees do is perfect. Their methods of flight, their social habits, their food gathered from flowers, their construction of honeycomb and their methods of defence. Now, is the perfection of the bees the result of being nurtured in hexagonal cells, or is the perfection of honeycomb the result of the perfection of the bees? Whichever way it is, it is obvious that to achieve perfection in other ways, man must first perfect his surroundings.7

.

Brewster thought big. He wanted to re-engineer society according to the principles of the honeycomb. Proceeding from a geometric figure meant his plans could be infinitely up-sized or down-scaled, and extended in any direction. After building his house, Brewster began planing ‘ideal buildings for the future’, hexagonal skyscrapers: hives for people. Several models remain

.

Certainly it seems to help many to personify God but we must realise that much of the guidance that seems to come to us from without really comes to us from within by the ability of the subconscious mind to recognise Truth much more surely than the conscious mind. The subconscious mind knows and is Absolute Truth which is God.8

.

Brewster was an embattled correspondent. In reading his letters, one senses his impatience at the stupidity and blindness of others, their failure to recognise a simple, self-evident truth. They were the dogmatic ones. Driven by faith, Brewster was resolute. The idea that the hexagonal bracing might make his aeroplane wing weaker and heavier because of its complexity, its number of joints, didn’t cross his mind for a second. According to one of his sons, himself an apiarist, even the bees didn’t like the hexagonal hive-boxes Brewster built them. They made more honey when offered evil right-angled boxes to nest in.

.

The greatest change in thought in the history of the human race was brought about by the birth and teachings of Jesus Christ. A very great change in thought was also brought about when Columbus discovered America in 1492. Until then it was accepted that the world was flat … Instead of changing to round principles, man has gone merrily on his way, still acting as though it was a flat, square world, planning his cities on the square, and generally acting on quite the wrong principles altogether. Our present square age should really belong to the pre-Columbus days when men thought that the world was flat so that it is an anachronism that is nearly 500 years out of its time.9

.

Brewster claimed his philosophy was not only true, but Truth with a capital T. Lack of doubt made him utterly creative. He never wasted time questioning the rightness of the hexagon, he simply proceeded to apply its principle to more and more things. He was as busy as a bee. As he developed more applications for his Norian thoughts, his world changed. What might initially have seemed like a nifty idea with some practical application became thoroughly mystical—an obsession. As time passed, Brewster’s quantitatively excessive production of thoughts and things made for a qualitative change in his world. The logic of his interpretations and arguments became increasingly intricate, convoluted, energised almost by their own density. Of course, he loved circular arguments. Norian thought became progressively self-referential and implausible, dogmatic and mannered, immune to attack.

.

Now we have it put into verse

The secret of the universe

Inter-invigoration and inter-control

And inter-dependency within the whole

Of forms, of Truth and Love and Light,

All to Masterpoint then held tight.

So that is what makes all things go,

That’s God’s eternal dynamo.

It is the interplay that counts,

Generating current that mounts

By alternation, to the sense of fun

On which our bodies thus are run.10

.

As the years passed, Norian philosophy became hermetic, ‘scholastic’, ingrown, a world unto itself. In 1973, John Hales published a series of three articles on Brewster in New Zealand Rolling Stone magazine. He hailed Brewster as prophet greater than Te Whiti, another Taranaki notable. The articles were illustrated with a selection of diagrams in which Brewster elaborated a Norian cosmology. This ‘theory of everything’ reconciled male and female principles; light, love, and truth; beauty and strength; clouded light, relative truth, and imperfect love. Norian thought provided all the answers, even the meaning of sex.

.

So in married life the man tends to throw off his excess strength and pass it to the woman. She turns the strength into magnetism. And by the interplay of bones and flesh between them, between hard and soft, the man getting harder and the woman getting softer, soft controlling hard, he, iron, responding to her magnetism with energy, passes more light and iron into her and receives back from her some of her magnetism. This magnetism energises the remaining iron in his body and both bodies are much invigorated electrically by perfect love, and each should feel on top of the world.11

.

In Brewster’s thought, there was continual equivocation between the empirical and the abstract, the concrete and the spiritual, nature and culture, God and the submerged shapes of mind. As we know from the history of the discourses around abstract art, an idealist geometric formalism such as Brewster’s can pass itself off as, at once, practical and spiritual, rational and mystical, modest and grand, discrete yet infinite, nothing yet everything. Such an approach provides a grab bag of exchangeable, even diametrically opposed cover stories, while claiming an essential coherency. Brewster’s discourse was similarly all-embracing, permitting him to equivocate between different notions and species of Truth. In conversation Brewster could easily side-step critique by simply sliding the problematic metaphor or motif into a different branch of his thinking, where the contradiction miraculously disappeared leaving the congregation wowed or exasperated.

.

The Spirit now with flag unfurled

Is setting out to rule the world,

New ways of life men have to live:

Not just to get, but seek to give.

Fresh impulse now receives its birth,

All promise kept right here on earth,

Then will be formed the world right through

‘Twixt Holy Cities, old and new,

An axis firm on which to turn

That Spirit may the brighter burn

To light the way of Truth and Life:

Ready is the Lamb to take His wife.12

.

Increasingly Brewster came to understand the invention of Norian ‘beewise’ construction methods as the dawn of a new epoch of consciousness for mankind. In 1973, after Nettie’s protracted illness and death, he wrote an elaborate account, titled ‘The Harmony between the Norian Story and Chapter 11 of the Book of Revelation’. In it, he understood their lives as fulfilling biblical prophesy. He and Nettie were identified as the two witnesses. ‘And I will grant my two witnesses authority to prophesy for one thousand two hundred sixty days, wearing sackcloth.’ In Brewster’s dense manuscript, and in the fifty verses of Norian thoughts he soon published, Brewster explained that God had commanded him to create a hexagonal Holy City at the foot of Mount Egmont, there to await Christ’s return. And so, in 1974, acting under the influence of higher powers, Brewster dismantled the Hexagon House and started work on his New Jerusalem. Subdivision would be triangular with hexagonal community areas. The Norian Builders Limited project was to be ‘a remarriage of spiritual and practical truth with reality’. Brewster died in 1978. The Holy City never got off the ground.

.

Roundways and by the use of them

The Holy City—New Jerusalem,

The Bride of Christ—it must arise

Pure and perfect before our eyes.

And then it will be heard by some

The Spirit and the Bride Say Come.13

.

All of Brewster’s thinking, building, writing, and preaching were part of a bigger, integrated project. This project involved making over reality in accord with ‘the subconscious’, which he understood to be, not subjective and gnarly, but objective and pure. The subconscious, or rather his subconscious, was Absolute Truth—God. To say Brewster had delusions of grandeur is an understatement. He, quite simply, conflated himself with The Almighty. Thus, isolated geographically and psychologically, he became lost in his dream.

The relics of the Norian grail-quest bear testament to a remarkable New Zealander. In fusing aspects of arcane thought, utopian modernist imperatives, evangelical Christianity, and Kiwi do-it-yourself, Brewster created something unique. And yet the Norian Story is also terribly sad, an Icarian tragedy: the plane that didn’t fly, the congregation that did not believe, the Saviour that did not return, a world that remains right-angled.

.

All quotes are from Edgar Roy Brewster.

- Hexagon House Souvenir (1957), sections 1–2.

- Ibid, 12–3.

- Ibid, 15–6.

- Ibid, 35.

- Ibid, 26.

- Letter to the Postmaster-General, 7 September 1960.

- Hexagon House Souvenir, 41–2.

- Quoted in John Hales, ‘Second Coming: Part 3’, Rolling Stone (New Zealand), 7 June 1973: 38.

- Hexagon House Souvenir, 40.

- Norian Thoughts (Stratford: Conical Hill, c. 1973), verses 21–2.

- Quoted in John Hales, ‘Second Coming: Part 2’, Rolling Stone (New Zealand), 24 May 1973: 37.

- Norian Thoughts, verses 46–7.

- Ibid, verse 50.