(with John McCormack) Art Asia Pacific, no. 2 (1993).

For at least the last fifty years, Pakeha have been voraciously appropriating Maori forms to express a distinct national identity. Our Sellotape is called Tiki Tape, our All Blacks do the haka, and our national airline has a koru as its trademark.

Recently, there has been much debate over the appropriation of Maori forms in the work of Pakeha artists.1 The debate has split into prosecution and defence. The prosecution has challenged Pakeha for their disrespect and ignorance of Maori culture, casting appropriation as sacrilege. The defence has justified appropriation under the first amendment, asserting an artist’s right to free speech, to challenge and contest cultural values. The two parties have simply talked past each other, and the question of cross-cultural borrowing has not been addressed as part of a cross-cultural debate in which the very terms of right and wrong might be recognised as culturally relative.

In 1992, the Auckland painter Dick Frizzell entered the debate head on with his Tiki exhibition at the Gow Langsford Gallery in Auckland. The irreverent works in this show re-presented Maori motifs through a variety of styles, derived from both modern art and low art. Frizzell depicted tiki and manaia motifs through the languages of cubism (Tiki with Chair Caning, Leger’s Lizard, and Architiki), vorticism (Vorticist Tiki), moderne (Giant Double Moderne Manaia), and art deco (Art Deco Tiki); and with reference to comics (Wacky Tiki Goes Monumental, Goofy Tiki, and The Spirit Moves Among Us) and advertising (Grocer with Moko and Double Feature).

During debates around the exhibition Magiciens de la Terre, art critic Thomas McEvilley wrote: ‘A sensitive exhibition defines a certain moment, embodying attitudes and, often, changes of attitude that reveal, if only by the anxieties they create, the direction in which culture is moving.’2 This may be equally true of the insensitive exhibition. Certainly, Frizzell’s Tiki show was a knowing intervention into contested territory. It came with its defence already prepared in the form of a catalogue with essays by both Pakeha and Maori writers.

The show was bound to draw flak. Frizzell was questioned on television; Stamp magazine ran an interview with Maori writer Ngahuia te Awekotuku and an essay by Maori filmmaker Merata Mita, both critical of the exhibition. Te Awekotuku insisted: ‘Frizzell must either be exceptionally naive and blissfully unconscious or else bloody cheeky and insolent to have done what he has done. You know, the more I look at the work and the more I think of the man the more inclined I am to consider the latter, because all of that work is hacked-out from the suppurating wounds of our pain as a people, and we don’t need that now; we don’t need shit like this now. No, we do not.’3

These words echo Te Awekotuku’s 1986 dismissal of Gordon Walters. When shown a photograph of Walters’s 1968 abstract koru painting Mahuika, she said: ‘I can only respond, at this point anyway, as an individual and as a Maori, as a Maori woman. I think it’s damn cheeky! The insolence of the man is extraordinary! The gall! The sheer gall! Mahuika is … a lady of fire, of strength … and there she is, all black and blue! Frost in the night. Weird.’4

Te Awekotuku reads Frizzell’s and Walters’s works in a similar fashion, without acknowledging that their historical contexts—and the artists’ motives—were very different. Frizzell paints tiki knowing that they are contentious; he paints them in order to enter the debate. His works are about appropriation in a way Walters’s works never were. Walters would never have claimed that he was happy to ‘move things along a bit and stir up what is such a moribund debate’.5 Walters never sought nor anticipated the controversy his work would later receive. His work was not made with those issues in mind, since those issues were not clearly apparent at the time he made his koru paintings. In this, and many other ways, Frizzell’s art is different from Walters’s.

So what were Frizzell’s intentions? He has said: ‘I made a visit to the East Coast at the beginning of 1992 looking for shonky Maori art, but couldn’t find it. It seemed to have disappeared as part of a cleansing, leaving only high art and no lows. I thought I’d paint a whole lot of shonky art to bring back the stuff that was missing. Wacky and Goofy Tiki were attempts to push the low art thing as far as possible.’6

Frizzell has always defined himself in opposition to the high brow. His slick paintings have spoken eloquently on behalf of the unsophisticated, the wooden, and the marginal. In the early 1980s, he drew on the art of comics and ‘bad’ painting; more recently, he has ministered to the neglected regional landscape tradition. Frizzell’s tiki continue his project of celebrating low art. If we take him at his word, the low art being celebrated is a ‘shonky Maori art’ he thinks he remembers but can no longer find.

Speaking of contemporary Maori art, Frizzell has argued: ‘The idea that you can keep a culture alive by choking it to death is ridiculous … sometimes you have to turn it upside down and shake it around a bit.’7 Such a diagnosis seems crass and presumptuous, particularly coming from a Pakeha, but it tallies with concerns being voiced within the contemporary Maori art scene. For instance, George Hubbard, one of the writers in the Tiki catalogue, has been anxious to debunk an essentialism that would deny Maori identity in works that do not follow a narrow prescription. Concerned that a major dimension of Maori experience is being shut out, Hubbard has been active in promoting what many would see as bad or inauthentic Maori art. He has worked with Maori graffiti artists and managed Maori rap bands. He has also recently curated several exhibitions which ‘question the binary opposition of Maori/Pakeha’.8

This said, we must admit that Frizzell’s works have less to do with addressing the dynamics of contemporary Maori art than with a Pakeha tradition of appropriation. Indeed, his works are about the very problems his critics would have him merely exemplify. In Grocer with Moko, Frizzell makes over a classic trademark, the Four Square grocer, as Maori. The moko, a sign of high rank in Maori society, is applied here to the gnomish caricature of the servile shop-keeper.

There is something familiar but painful about this and other Frizzell tiki. They embody disturbing contradictions. They remind us of a recent past in which we were blissfully insensitive to the politics of cultural interaction and could play at being white Polynesians. His tiki are bitter-sweet. They are at once nostalgic for those days and make light of them.

Many of Frizzell’s modern-art tiki suggest not ‘shonky Maori art’ but shonky Pakeha art. They suggest the modern-art styles that were becoming current in New Zealand art in the 1950s.9 Isolated from the main arenas of modern art, New Zealand artists came up with their own mixed-up version of modern art, using modern styles with little understanding of the contexts from which they derived. Just as ‘primitive’ art played a key role in the work of modernists like Picasso and Klee, some New Zealand artists looked to the indigenous art at their own back door. We remember the fine examples of Walters and Theo Schoon, but there were also the more lumpen appropriations of A.R.D. Fairburn, Dennis Knight Turner, Eric Lee-Johnson, E. Mervyn Taylor, Avis Higgs, and Co. In Europe, ‘primitive’ art was assimilated into a local idiom—that of modernism. The New Zealand situation was very different. Our artists typically misunderstood not only the local ‘primitive’ art they were appropriating but also a modernism that must have seemed equally distant. It is this state of compounded confusion that Frizzell recalls in his tiki.

An old press photograph shows the New Zealand painter Sam Cairncross with a 1948 self-portrait, rendered in the manner of Van Gogh. He even signs the work ‘Sam’, after ‘Vincent’. To his left, floating, isolated in space, is a generic tiki. The tiki appears to grin, taunting the earnest painter. What kind of a self does this work represent? Is the tiki to be read as a personal talisman or as a symbol of radical difference? Cairncross brings together two motifs of distinct origin—which to him would each have symbolised some kind of authentic identity—in lieu of an authentic self of his own. And just in case the viewer might doubt the authenticity of the work, Cairncross pretentiously titles it in French, Portrait de l’Artiste avec Tiki.10 Frizzell’s tiki, like the Cairncross self portrait, seem clumsy and hybrid. One difference is that Cairncross’s self portrait was done in all seriousness, forty-four years earlier.

Frizzell’s tiki comment on works, like Cairncross’s self portrait, that mix ‘primitivism’ and modernism and that express the dilemma of Pakeha identity—an identity implied in the gap between a local that is foreign and a ‘home’ that is distant. It is said that lack of authenticity makes art appear bad. Paradoxically, it is just such a lack which is at the heart of this authentically Pakeha work.

With his tiki, Frizzell is not trying to co-opt Maori authenticity. Rather he explores and celebrates the play of (in)authenticities that define Pakeha identity. Frizzell’s tiki assert Pakeha ‘primitivism’ not as something serious, powerful and oppressive, but rather as something wacky, goofy, and deeply mistaken. So although Frizzell may perversely relish an aspect of the ‘dominant culture’, he is certainly not asserting it as dominant.

Frizzell grants us an opportunity to consider the quaintness of Pakeha culture. He may know next to nothing about Maori culture, but Frizzell sure knows a lot about being a Pakeha.

.

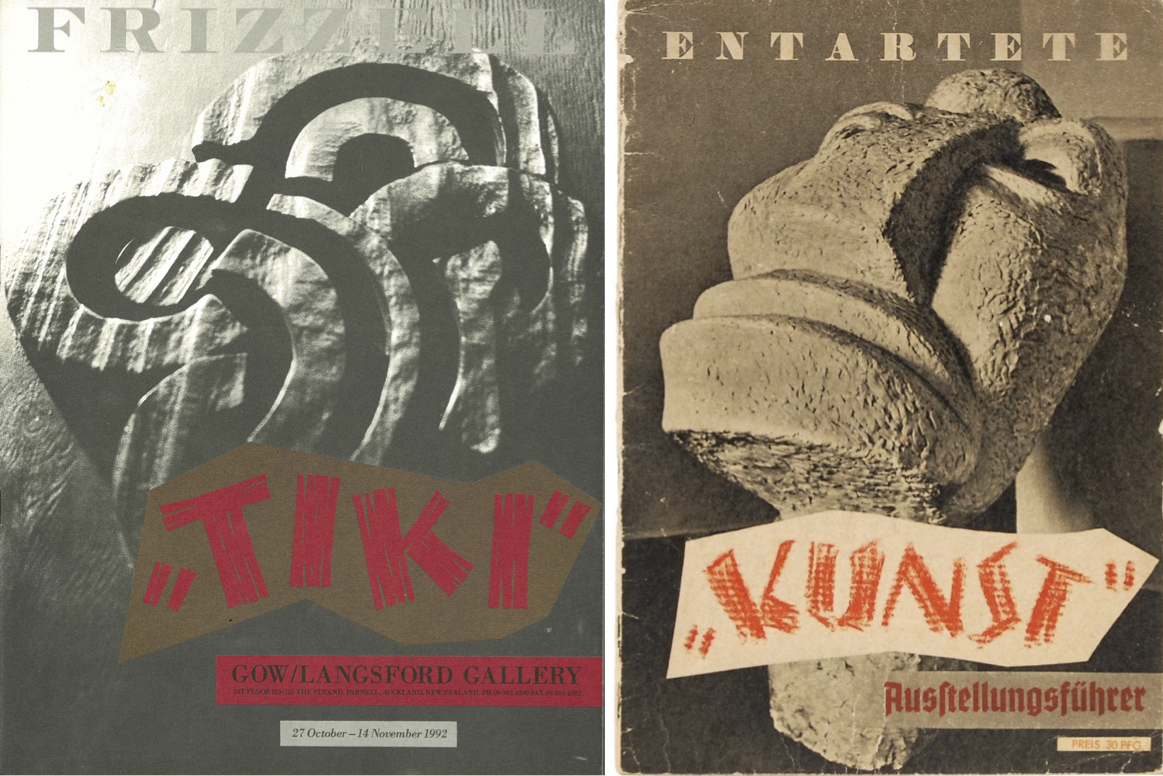

[IMAGE: The catalogue covers for Dick Frizzell: Tiki (1992) and Entartete Kunst (1937)]

- Published writing in this area constitutes only a fraction of the actual debate. Key texts include: ‘Ngahuia te Awekotuku in Conversation . . .’, Antic, no. 1, 1986: 44–55; Leonard Bell, ‘Walters and Maori Art: The Nature of the Relationship’, in Gordon Walters: Order and Intuition (Auckland: Walters Publication, 1989), 12–23; Rangihiroa Panoho, ‘Another View of the Photographs of Laurence Aberhart’, Antic, no. 8, 1990: 22–7; Ian Wedde, ‘Talking to the “Wounded Chief”: Augustus Earle and Gordon Walters’, in Now See Hear!: Art, Language and Translation (Wellington: Victoria University Press, 1990), 39–42; Rangihiroa Panoho, ‘Maori, at the Centre, on the Margins’, in Headlands: Thinking through New Zealand Art (Sydney: Museum of Contemporary Art, 1992): 122–34; Stuart McKenzie, ‘Ticky-Tacky’, in Dick Frizzell: Tiki (Auckland: Gow Langsford Gallery, 1992).

- ‘Marginalia: Thomas McEvilley on the Global Issue’, Artforum, March 1990: 20.

- Dick Frizzell, ‘Tiki’d Out’, Stamp, December 1992–January 1993.

- ‘Ngahuia te Awekotuku in Conversation . . . ‘: 50.

- Dick Frizzell, ‘Tiki’d Out’.

- In conversation with John McCormack, January 1993.

- ‘Tiki’d Out’.

- George Hubbard curated Choice! (1990) and Cross Pollination (1991), for Artspace, Auckland. These exhibitions were accompanied by broadsheets, which Hubbard wrote with Pakeha panbiogeographer Robin Craw. The Choice! text was later published in Antic, no. 8, 1990: 28.

- The 1950s is a key area of concern for much recent New Zealand art. See Robert Leonard, ‘Mod Cons’, Headlands: Thinking through New Zealand Art, 161–72.

- Perhaps we do Cairncross a disservice. Portrait de l’Artiste avec Tiki may have been painted in France. Cairncross had a year’s study there, returning late 1948. The photograph was reproduced in the Evening Post, 21 November 1948, illustrating the article ‘Much Benefit from Trip Abroad: New Subtlety in Cairncross’s Art’.