Sister Corita’s Summer of Love, ex. cat. (Wellington and New Plymouth: City Gallery Wellington and Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, 2016).

.

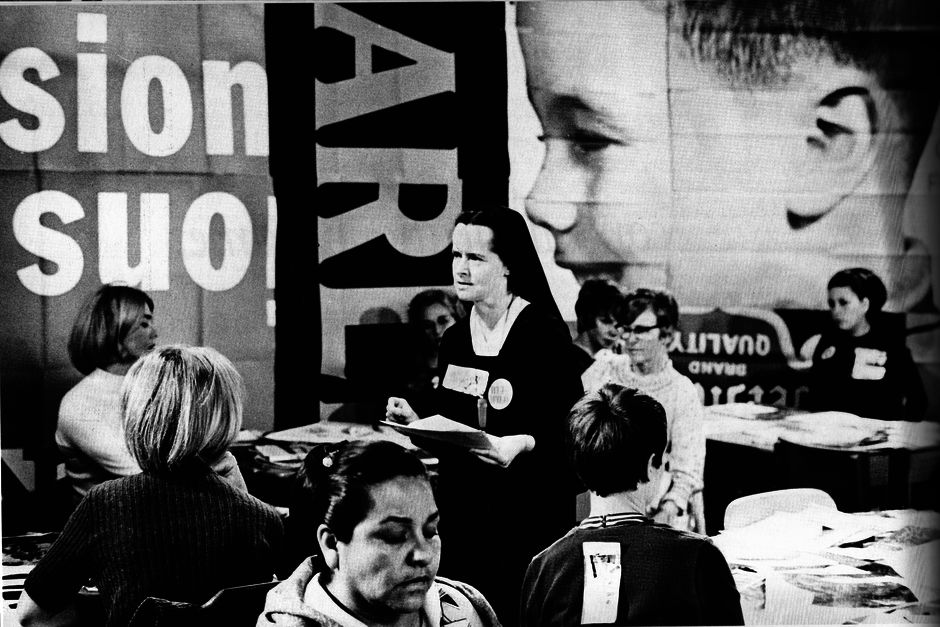

In the 1960s, nuns were out and about, playing guitars and singing songs, riding motorbikes and attending to the flock. The Encyclopedia of Bad Taste devotes a two-page entry to the ‘perky nun’.1 It opens with a Belgian Dominican, Sister Luc-Gabrielle, who became world famous with her 1963 hit song ‘Dominique’, spawning numerous imitators (including the Singing Nuns of Jesus and Mary). Debbie Reynolds played a role based on her in the 1966 movie, The Singing Nun. The Encyclopedia’s authors go on to explore the ubiquity of playful, modern nuns in other 1960s American movies, citing Lilies of the Field (1963), The Trouble with Angels (1966), and Change of Habit (1969), in which Mary Tyler Moore plays sexy Sister Michelle, whose vows are tested by a dashing Dr. Elvis. Of course, wholesome Sally Field, fresh from Gidget, would become the ultimate perky nun, as Sister Bertrille in the television series, The Flying Nun (1967–70).

Underpinning the perky-nun phenomena was something less laughable—massive reform in the Roman Catholic Church. In the late 1950s, the new Pope, John XXIII, saw that his Church was out of touch with its communities. It was time for the Church to open its windows and let in some fresh air, as he put it. From 1962 to 1965, the Roman Catholic Church convened the Second Vatican Council (a.k.a. Vatican II), seeking to become more relevant, to renew and renovate itself. As a result, mass came to be performed in the vernacular, rather than in Latin, with priests facing the congregation. Elaborate regalia was downplayed, Catholics were permitted to pray with non-Catholic Christians, and friendship with non-Christian believers was encouraged. Plus, priests and nuns were prompted to venture out, to engage with their communities.

Surprisingly, the Encyclopedia fails to mention the most famous nun artist, Sister Corita Kent. It could have—she was certainly a celebrity. Based in a progressive, liberal order, the Immaculate Heart of Mary, in Los Angeles, Kent was a poster girl for Vatican II. During the 1960s, she became renowned for her dynamic, brightly-coloured, text-based screenprints, whose forms, colours, and words expressed themes of hope and kindness, peace and love, and social justice. She also wrote and designed books, art-directed festivities, and produced a mural for the Vatican pavilion at the 1964 New York World’s Fair. (The Fair’s theme was ‘Peace through Understanding’, and the Vatican pavilion’s theme was ‘The Church Is Christ Living in the World’.2) In 1966, the LA Times chose Kent as one of their ‘Women of the Year’, and, in 1967, Harper’s Bazaar included her in their ‘100 American Women of Accomplishment’. She also appeared on the cover of the 25 December 1967 issue of Newsweek under the banner ‘The Nun: Going Modern’.3 Several films were made about her.

For her works, Kent drew inspiring words from scripture, from writers and thinkers, from poems and pop-song lyrics, and especially from road signs, commercial packaging, and advertising. She piggybacked on the visual immediacy and urgency of commercial messages, often ventriloquising her right-on thinking through appropriated advertising copy—those madman inventions designed to worm their way into our heads ‘like liquid gets into this chalk’.4 For Kent, Pepsi’s tag line ‘Come Alive!’ suggested the Resurrection and a prompt to get a life. Wonder Bread stood in for the Host. The line, ‘A Man You Can Lean On’, came from a Klopman fabrics ad, and ‘See the Man Who Can Save You the Most’ from Chevrolet. Kent also used road signs as metaphors for spiritual guidance—‘Turn’ and ‘One Way’, of course. Exemplifying Vatican II’s imperative to speak in the common language of the people, Kent’s work presented a world of profound religious significance lurking beneath the fleeting secular surfaces of the everyday.

In the past, there have been many attempts to update Christianity, to make it relevant, to express its sentiments in a more familiar, contemporary idiom, to make what was historical seem timeless. In the renaissance, painters rendered Christian stories as if they were happening in the here and now. In the 1920s, English painter Stanley Spencer imagined the Resurrection occurring in his local village of Cookham, and, in the 1940s, Colin McCahon relocated the Christian story to New Zealand’s back blocks, adding speech bubbles from a Rinso packet. In the 1960s, Kent found God in the supermarket and on the interchange.

With her feel-good thoughts, Kent embodied her times, furnishing bumper-sticker homilies for the Age of Aquarius. Her work promoted the civil-rights movement, protested American involvement in the wars in South-East Asia, and lamented the assassination of prominent American political figures, including Martin Luther King and, those Catholic martyrs, the Kennedys. Her project was timely. It coevolved with American pop art and the counterculture, and anticipated the Jesus Movement—a brand of evangelical hippie Christianity whose preachers wore blue jeans and spoke street.

Kent’s prints operated in a space between the hygienic authority of hard-edged corporate branding and the funky organicism of late 1960s, West Coast, art-nouveau-inspired counterculture posters. Although her graphic treatments recalled advertisements, their hand-drawn, distorted, distressed, fractured letter forms looked less Swiss-corporate, more ‘personal’. Kent played up their less-than-perfect, handmade quality, flaunting drips and smears, inconsistencies and registration slips. Her faux-informal, ‘higglety-pigglety’5 typography was often based on her photos of bent and crumpled signs and on her found-text collages. Her prints also featured her spiky handwriting, with its quirky capitalisation, suggesting intimate communication (letters and commonplace books).

Kent didn’t operate in an art vacuum. She was a magpie and networker. While her work often feigned a direct, naive, childlike quality, it was steeped in art and graphic-arts history—she had an MA in art history. In her work, we can see the influence of Matisse’s cutouts, abstract expressionism, Saul Bass’s graphics, Charles and Ray Eames’s folksy modernism, and Andy Warhol—she caught and was inspired by his breakthrough Campbell’s Soup can show at LA’s Ferus Gallery in 1962. Her art classes at Immaculate Heart College became a mecca for the avantgarde, with eminent visitors like film director Alfred Hitchcock, composer John Cage, and geodesic-dome prophet Buckminster Fuller.

Kent’s art may have been easy on the eye and gentle on my mind, but it was smart graphically. Take her multi-panel work, Circus Alphabet (1968). With a panel for each letter of the alphabet, each panel does something different, riffing on a basic idea, building novelty. Kent contrasts and scrambles graphic and typographic techniques past and present, mixing found imagery (derived from antique sources) and text (in different typefaces alluding to different printing technologies), translating them all into the pop-graphic economy of colour-separated screenprinting. Circus Alphabet was both timely and retro. Its appropriation of vintage circus imagery was keyed to then-current counterculture nostalgia. It was made the year after the Beatles released Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band—which famously included the song ‘Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite’, which was based on a Victorian-period circus poster—and its eye-popping, fluoro colour scheme was similarly psychedelic.

Some consider Kent an unsung heroine of pop art. Currently, there’s a campaign to squeeze her into the pop-art pantheon. This has been the agenda of several recent shows, notably 2015’s Corita Kent and the Language of Pop.6 However, for all this, Kent represents something of a dilemma. At first glance, her work looks like pop art—and the documentation of the Mary’s Day festivities she art directed may remind us of happenings (hippie be-ins, more like)—but, in her time, she was remote from the pop-art discussion, being understood and distributed more as a graphic designer. At the time, she was not included in books on pop art, although she certainly is now. Corita Kent pop artist belongs to a new idea of pop. She is a product of revisionism.

Actually, at the time, Kent’s work ran against the grain of pop. It was an anomaly. Pop art started out as aggressively secular, a response to abstract expressionism’s quasi-religious and humanist pretensions. Pop artists embraced commercial imagery to escape abstract expressionism’s gravity and mystique—it was lite, but with a purpose. In the 1950s, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns had satirised and evacuated the expressionist brushstroke, putting it in inverted commas, mocking its claims to immediacy. But, it has been argued that pop art only really began when Warhol finally ‘dropped the drip’ around 1962.7 Yet, even after he did—and while clearly under his influence—Kent kept leaning back, the other way. Her hand-cut and hand-painted letters asserted a personal, informal, warm-fuzzy humanism—an expressive ‘brushstroke’ logic.

Even after Roy Lichtenstein gutted the brushstroke in his Brushstrokes works of 1965–6, Kent continued to reiterate brushstroke logic as shorthand for unmediated creativity, spontaneity, and freedom, personal expression and love. In the 1970s, after leaving the order, the brushstrokes became explicit. In 1971, she created Rainbow Swash, a public work on a giant gas tank in Boston. Seemingly blind to her support’s toxic, industrial function, she decorated it with a rainbow of colour brushstrokes. No irony.8

Irony was irrelevant to Kent, but crucial for pop. The 1960s was a time of both excitement and paranoia about advertising and consumerism. This ambivalence found its ultimate expression in James Rosenquist’s massive wrap-around painting F-111 (1964–5), in which ad images were set into an image of the F-111, the US’s new tactical fighter and bomber plane destined for Vietnam, partly camouflaging it.9 Textbook irony. The 1960s were complicated. While anxiety about consumerism underpinned the counterculture (drop out), it was itself a product of middle-class affluence (only some could afford to drop out)—and Madison Avenue moved quickly to understand and exploit the hippies as a market. But Kent was not so interested in complexity. She suppressed the contradiction between secular advertising and her religious message, even though this was and remains the source of her work’s frisson for audiences.

Kent was agreeable. She is seen as an activist, but her politics were limited: war is bad, love one another, be nice, ‘today is the first day of the rest of your life’. Beyond rubber-stamping causes, her work offered little analysis or argument. While making Catholicism palatable, she steered away from thorny matters, like birth control and abortion, gay rights, or what to do about capitalism.10 Perhaps her work anticipated slacktivism, our current habit of branding ourselves with righteous issues rather than actually doing anything about them: buy the button badge or poster, like it on Facebook.

The tendency to frame Kent as a political activist leans on the hostility she endured from LA’s super-conservative Archbishop, Cardinal James Francis McIntyre. A Vatican II resister and stick-in-the-mud, he wouldn’t get with Catholicism’s new-and-improved programme. He was no fan of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in general or of Kent in particular. Indeed, he castigated the good sister for daring to compare the Virgin to a ripe tomato in her famous print, The Juiciest Tomato of All (1964), and resented her visibility and popularity. Cardinal McIntyre suppressed the Immaculate Heart order. In 1967, after they began promoting liberalism and abandoned the habit and compulsory daily prayer, he barred them from teaching. He is blamed for Kent’s leaving the order in 1968. Because of him, she occupies an ambiguous position. We’re able to cast her as epitomising a sea change in the Catholic Church and as a radical within it—whichever we prefer.

Kent’s works may be upbeat and friendly, but they’re also righteous—full of moral imperatives. Her bright colours and simple forms speak to the child in us, instructing us in charity and hope, peace and love, keeping us on the straight and narrow. Not everyone took kindly to her Sunday-school rainbows. For some of the artists who followed, her work was pure—pure cheese. One LA artist certainly thought so. Mike Kelley had been raised a Catholic in a working-class Detroit family, and Kent’s images were among the first things he had seen and thought of as art. In 1987, the year after Kent died, he made a series of handmade felt banners that included various Kent pastiches: Trash Picker (a vibrant, happy-clappy patchwork, bearing the pathetic legend, ‘I Am Useless to the Culture but God Loves Me’), The Escaped Bird (a childish, abject School-of-Paris bird accompanied by the word ‘Joy’), and Let’s Talk (a cookies jar, with the injunction ‘Let’s Talk About Disobeying’). Ever the contrarian, Kelley cast Kent’s messages as saccharine, asinine, and a tad sinister.11

Kelley and Kent were oil and water. Kent doesn’t relate to the suspicious, conflicted, cynical, agonistic (aka ‘critical’) attitude we typically associate with contemporary art. And she doesn’t easily fit into pop, so much as sit alongside it. Now, forcibly inserting her into the pop-art canon makes pop art itself seem different. Her work offers an oblique vantage point for considering pop art and its legacy. For instance, it draws attention to religious subtexts in the work of canonical, supposedly secular pop artists—her contemporaries. Take Warhol, a Ruthenian Catholic, a committed church goer. Kent reminds us of the icon-like quality of his Marilyns; of his religious preoccupation with sanctity, death, and disaster; and of his late The Last Supper works (1986–7). In The Last Suppers, Warhol collages a Dove soap logo (suggesting the Holy Spirit) and a body-building ad slogan, ‘Be a SOMEBODY with a BODY’ (suggesting the Incarnation), into Leonardo’s masterpiece—a classic Kent move. Similarly, with lapsed-Catholic Ed Ruscha, also from the City of Angels, Kent’s proximity alerts us to his preference for visions of miraculous light and for painting loaded religious words (including ‘Gospel’, ‘Faith’, ‘Mercy’, ‘Purity’, ‘Sin’, and ‘The End’). Etcetera.

In the beginning, pop art and abstract expressionism were polar opposites. However, as we increasingly engage with pop art independently of its formative issues with abstract expressionism, this oppositional characterisation loses its grip. These days, we increasingly enjoy pop art’s belied quasi-religious edge, as artists conjure with the auratic power of mass-media images and the magical animism of commodity fetishism. Suddenly, pop and religion don’t seem necessarily antithetical. Kent’s pre-critical, affirmative approach also resonates with Jeff Koons’s neo-pop, post-critical, people-pleasing work. Koons compared his topiary Puppy (1992) to ‘the Sacred Heart of Jesus’.12

In New Zealand, we see such magical thinking at loose in the work of artists negotiating pop’s legacy. For instance, Michael Parekowhai’s early word sculpture, ‘Everyone Will Live Quietly’ Micah 4:4 (1990), discovers the sacred in the profane. The then-young Maori artist spells out the name of the Old Testament prophet Micah four times in block letters, like a trademark, and titles it with an optimistic quote from Micah’s brief book. (Chapter 4, verse 4—get it?) The letters are laminated with a common Formica that resembles sacred pounamu. Like many of Parekowhai’s early works, this piece suggests the way post-contact Maori read their own thinking into the products of a dominant culture, particularly the Bible, making them their own. The parallel with Kent is clear, but reversed. She imposes enduring Christian import on the secular world, whereas Maori projected their urgent needs onto the Bible.

In the mid-1990s, Jim Speers similarly celebrated poetic-religious-transcendent possibilities persisting in corporate liveries and advertising lightboxes. His lightbox installation, Honeywell (1998), resembles a disassembled computer-company shop sign. Speers turns a found company trademark—to which we would normally not give a second glance—into a utopian haiku. Split into three units, regularly spaced across the floor, Honeywell combines 1960s secular pop (appropriated trademarks) and 1960s secular minimalism (equally spaced, industrially fabricated boxes) to create a quasi-religious beacon—a lighthouse.

But, the antipodean artist who best exemplifies the conflation of religion and pop is an Australian. Scott Redford was born on the Gold Coast, a famously trashy, culture-free zone—a shameless mash-up of LA, Vegas, and Miami aesthetics and lifestyles. Since the turn of the millennium, Redford has embraced the Coast’s slick aesthetic, imagining the residents of Surfers Paradise to be already living in the promised land, albeit oblivious of the fact. He’s made surfboard crosses and has emblazoned surfboards with impossibly futuristic, portentous dates; he’s made paintings using surfboard-making materials and techniques, where commercial logos become mystic talismans; and he’s made photographs of surfers carrying a surfboard cross and pointing to heaven in the manner of Leonardo da Vinci’s John the Baptist (1513–6). For Redford, the local surfers have replaced Galilee fishermen. Maybe it’s a joke, maybe not. For a moment, Redford asks us to consider his birthplace as a singularity—the marriage, conflation, or collapse of spirituality and capitalism, post-modernism and eschatology. Redemption.

God is everywhere: Kent finds him in the supermarket, Redford at the beach. And he is inescapable. It seems, the closer you get to the secular, the more you eliminate religion, the more religion raises its head.

Kent’s legacy also operates outside of art, in those contemporary forms of American Christian propaganda that have learnt from advertising and pop culture in order to compete with it, to turn us on to God instead of godless materialism. This is particularly visible in the use of computer-generated animated type in Christian evangelical videos, to make religious messages dramatic and infectious; to criticise us, to motivate us. These videos promote all manner of messages across the denominational and political spectrums. The church has become a ‘video ministry’—a videodrome.

Some of the videos are sophisticated, some mawkish. One King Productions’ hectoring Fan or Follower (c. 2011) is based on a stirring sermon from Pastor Darrell Schaeffer of Ohio’s One Way Church.13 It has the urgency and cadence of a disaster-movie trailer. As we hear the pastor and Co. inciting us to be not simply Christ’s fan but his follower, we also read the words—seeing reinforces hearing. Presented in a straight-up serif typeface, white on black, the words quiver, as though we are watching them in a state of rapture. As the diatribe builds to a crescendo, the tremulous words expand and explode in light as if in some cosmic cataclysm, leaving just one word on screen, the self-evident conclusion—‘Follower’.

Equally orgasmic is Revolution (2014).14 Director James Grochowalski, a motion-graphics designer for Central Christian Church in Las Vegas, calls his music clip an ‘inspirational mini-movie’. Based on the book of Romans, it asks ‘how we can be the hands and feet of Jesus in this hurting world’, and argues that ‘we shouldn’t just stand by and wait for change, we should be the change’. It features computer-generated block letters combined with geometric and flaming graphics, edited to generic electronic dance music. It is catalogued at Sermoncentral.com: ‘Tags: Change, Evangelize, Changed Life, Revolution, Be the Church; Audience: Teens, Adults; Genre: Emotional, Powerful, Reflective; Style: Progressive.’ Grochowalski says his videos are mostly played either at the beginning of services, to kick off the worship, or to set the stage immediately before the pastor speaks. Stirring stuff.

Like Kent’s prints, video sermons seek to make Christianity contemporary, vital, and viral. They use the latest techniques of persuasion to tell us what we need to know—and why wouldn’t they? I must say, I am split. I am not a Christian, but I see no good reason for Christianity not to advertise itself like any and every other belief system or product, to plead its case in the free market of ideas. But, I don’t buy it. I also know that Christianity, like all the great religions, is a man-made thing. It originates long, long ago, in a place far, far away, when the issues were different—a time before the enlightenment, before science, before feminism, before Wonder Bread, before pop, before the pill, before we put someone on the Moon—and it speaks to the needs of those times, not to now. In the rush to update it, to make it contemporary, to make the mummies dance, that is lost—history collapses.

On the other hand, the Christian arts of Kent in her day and the video ministers of today are also a reminder that we can never escape history, that the church art of the Western tradition was always already advertising before advertising, and that, even in the most cynical work of the most sceptical pop and post-pop artists, religiosity lingers, like background microwave radiation from the Big Bang. Kent’s work reminds me of all this because it does and doesn’t fit into art history. Kent may not have made pop art at the time, but her legacy is remaking pop art now.

- (New York: Harper Collins, 1990), 243–4.

- The World’s Fair was not completely tolerant and inclusive. Andy Warhol’s mural on the exterior of the New York state pavilion, The Thirteen Most Wanted Men, was painted over.

- Susan Dackerman, ‘Corita Kent and the Language of Pop’, in Corita Kent and the Language of Pop (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Art Museums, 2015), 16.

- For non-antipodeans, I should explain. This was Mrs. Marsh’s inevitable refrain on Australian ads for Colgate toothpaste in the 1970s and 1980s. Colgate toothpaste gets into your teeth ‘like liquid gets into this chalk’.

- Karen Carson in Someday Is Now: The Art of Corita Kent, ed. Michael Duncan and Ian Berry (New York: Prestel, 2013), 126.

- Corita Kent and the Language of Pop (2015), Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA, and San Antonio Museum of Art.

- There’s a great story. Early on, Warhol did two paintings of a Coke bottle, one in a flat commercial-art style, the other a more painterly treatment, a nod to abstract expressionism. He asked filmmaker Emile De Antonio which was best. De Antonio went for the first. He said, ‘I think that helped Andy make up his mind … that was almost the birth of Pop.’ Warhol dropped the drip, negating both the hand of the artist and the transcendental status of art, consigning ‘handpainted pop’ to the past. See Benjamin Buchloch, ‘Andy Warhol’s One-Dimensional Art: 1956–1966’, in Annette Michelson ed., October Files 2: Andy Warhol (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2001): 39, fn22.

- The brushstroke has become a graphic-design cliché, regularly reiterated in arts-organisation and arts-festival logos as shorthand for childish creativity, expression, freedom, and happiness, at a time when contemporary art has largely lost faith in these values.

- The F-111 was then new. It would not enter service until 1967.

- By contrast, in 1967, prompted by the Church’s failure to fully implement the spirit of Vatican II, Luc-Gabrielle, who had already left the convent, released, under her new stage name Luc Dominique, her song ‘Glory Be to God for the Golden Pill’, defending contraception.

- See Cary Levine, Pay for Your Pleasures: Mike Kelley, Paul McCarthy, Raymond Pettibon (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013).

- See The Jeff Koons Handbook (London: Anthony d’Offay Gallery, 1992), 160; and Koons’s interview with Anthony Haden Guest, in Jeff Koons (Munich: Taschen, 1992), 33. See also Veit Loers, ‘Puppy, the Sacred Heart of Jesus’, Parkett, no. 50/51, 1997.

- www.youtube.com/watch?v=tiB6tCiVfu4.

- https://vimeo.com/101875301.