Unseen City: Gary Baigent, Rodney Charters, and Robert Ellis in Sixties Auckland, ex. cat. (Auckland and Wellington: Te Uru and City Gallery Wellington, 2015).

Auckland is a city of contrasts: a city of change: a city of people. Victorian wooden buildings jostle modern glass and concrete against a background of wharf derricks, silvered oil storage tanks, and the masts of pleasure yachts: a giant motorway sweeps across manicured front gardens and forgotten backyards: mini-skirts walk with lavalavas on pavements cluttered with telegraph poles, potted trees, and parking meters: front doors open onto hustling streets, back doors onto quiet bush.

—The Unseen City, 19671

.

This exhibition grew out of my longstanding affection for two works from the 1960s by then-young artists—the short film Film Exercise (1966) by Rodney Charters and the photobook The Unseen City: 123 Photographs of Auckland (1967) by Gary Baigent. Both works record a lost Auckland, its geography and culture. They capture a city in transition, contrasting a conservative, older generation with the beautiful people—it was the dawn of the counterculture. Both works cast roads, cars, and motorbikes in leading roles. Intentionally or not, Charters and Baigent left us time capsules.

Originally, my plan for the show was to juxtapose the film and the photos. Robert Ellis came in later, when the discovery of some 1960s drawings revealed how much his enjoyment of Auckland’s new motorways had informed his famous Motorway paintings.2

The works in the show are little known. For me, they have personal resonance. I was born in Auckland in 1963, so most of them were made when I was a small child. Although they tally with my earliest memories, they concern a place I never really knew. I suspect, for others—and in different ways—this show may also be something of a nostalgia trip.

.

Auckland has long been our largest city, the big smoke, our closest thing to a metropolis. In the 1950s, its population was increasing fast (in the 1960s, it would pass half a million).3 In response, motorways were built through the 1950s and 1960s, and the Auckland Harbour Bridge was opened in 1959. Motorways enabled suburban sprawl and turned Auckland into a car city. Today, as the population approaches 1.5 million, these monumental structures are associated with congestion and epic commutes, but, back then, they represented speed and access, innovation and growth—urban hygiene.

In 1957, Robert Ellis—a graduate of London’s Royal College—arrived in Auckland. He came to teach at Elam art school. The Motorway paintings he began making in the mid-1960s were informed by two distinct experiences of the city. In the first, the city was remote: in the late 1940s, during his national service in the RAF, Ellis had processed aerial photographs surveying German cities, where the war’s devastation was abstracted into patterns. In the second, the city was immediate: in 1958, he had bought a Ford Prefect and had learned to drive on Auckland’s new motorways. ‘That car altered my ideas about space, movement and time … very exhilarating’, he wrote.4

The Motorway paintings look improvised, like abstract expressionism, as if their subject matter might be an alibi for the artist’s painterly adventures. As they were not intended to be representations of any particular city, Ellis had huge freedom with the compositions—he could make his marks anywhere. The Motorway paintings are also ambiguous. For instance, they can be, and were, read both as exuberant celebrations of postwar expansion and as prophecies of congestion, ruin, and apocalypse.5 Similarly, the macrocosm of the city suggested the microcosm of the body—forms may be rivers, motorways, or roads, but, equally, could be sinews; arteries, veins, and capillaries; nerves and synapses. Ellis thus conflated the concrete infrastructure with the fleshy beings that inhabit it—and with himself.

Despite their urban subjects, Ellis’s Motorway paintings fitted the dominant paradigm of New Zealand painting, which Wystan Curnow has identified as ‘expressive realism’. Typified by Colin McCahon, expressive realism is a contradiction in terms, conflating the idea that the artist represents the world beyond himself (realism) with the idea that he represents the world within (expressionism). The expressive realist finds the truth of himself in his subject and the truth of his subject in himself; inside and out become as one. Ellis’s Motorway paintings are textbook examples. They offer a God’s-eye perspective on the city, as if it was observed from thousands of feet up, but they are also textured, drawing our attention to the expressive brushwork, to the canvas as coalface, equating the painter’s business with urban bustle itself. Ellis’s city’s structures and flows are his painterly gestures. This identification of the immediate self and the remote city is explicit in Ellis’s painting Self Portrait as a City (1965–6), where the city doubles as the artist’s head—as if the city was happening inside his head.

Ellis’s Motorway paintings may not specify Auckland as their location, but his inventive drawings in this show make the city’s influence explicit.6 In some, the city is named (Auckland Motorways, 1963, and Auckland City, 1964). Some feature recognisable sites, including Auckland Harbour Bridge (Pylon with Auckland Harbour Bridge, 1966) and the Dominion Road Interchange (City Suburban Motorways, 1964, and Homage to Pylons, 1968). Part observation, part fantasy, there’s a comic aspect to the drawings—spaghetti motorways veer off at roller-coaster angles. The drawing Motorways Heading North (1962) seems to have begun within a designated frame, but spilled out into the margins, colonising unused space, as motorways do. While the Motorway paintings present exclusively God’s-eye views, the drawings mix it up, offering a range of viewpoints and varieties of information. For instance, Pylon with Auckland Harbour Bridge conflates high and low viewpoints: the Bridge (viewed from on high) and a pylon (viewed from below) share a common blank background. The collision of terrestrial and celestial views—explicit here, but only implicit in the Motorway paintings—is reinforced by two microscopic inscriptions: one addresses the everyday reality of pylons and motorways, the other is the Lord’s Prayer.

Motorways not only enabled cities to expand, they also provided access to the hinterland, changing the relation between town and country. Two Ellis drawings in the show refer not to Auckland but to rural Te Rawhiti, up north, in the Bay of Islands, the ancestral lands of Ellis’s wife-to-be, Elizabeth Mountain. Te Rawhiti Marae with Motorway (1963) depicts Te Rawhiti marae from behind, with a motorway on the horizon. Motor Vehicle Bypassing Te Rawhiti (1964) goes the other way, with a car in the foreground and the marae, small, in the distance. Both imply that modernity threatens to destroy this close-knit rural community’s way of life—and this at a time when Maori were leaving their traditional lands for employment in the cities. And yet, the drawings are also fantasies. At the time, there was barely a dirt road at Te Rawhiti. When the metal road finally came, it would prove to be a mixed blessing. Rates increases forced locals off their lands, and, when it rained, mud and clay run-off from the road flooded properties and killed shellfish beds.7 In the 1970s, Te Rawhiti and Maori social, political, and economic issues would become central to Ellis’s work.

.

Motorways and roads traverse the city, linking different aspects of life—work and play, culture and nature, public and private. Rodney Charters made Film Exercise (1966) as a second-year Elam student. It’s a road movie—it’s structured around a journey. This eleven-minute, 16mm, black-and-white short film tells a simple story: a gorgeous girl (played by Shelly Gane, in real life an Architecture student) meets an enigmatic boy (Ted Spring, an Elam student) on a windswept West Coast Auckland beach. She strokes his motorbike suggestively, he draws on his roll-your-own cigarette nonchalantly. Following this brief courtship ritual, they drive off together, across the beach, through the Waitakeres, down the motorway, into the city. As night falls, they pass through Queen Street (the main drag). Finally, they head to a party in a run-down villa (in reality, an art-school share house in Mount Eden). There, boy unceremoniously dumps girl, preferring to hang out with his mates. Despite the promising set up, there is no boy/girl consummation. Disappointed, she exits, returning to the parked bike—perhaps the true love object for both.

What is remarkable about Film Exercise is not the story (there barely is one), but the way it is filmed. It is literally a ‘film exercise’. Sequences are shot in distinct styles. The opening beach scene looks like advertising. (At the time, Charters was paying his way through art school by taking photographs for ad agencies and magazines.) A sequence with snaking, strobing road markings, filmed from the bike riders’ point of view, recalls Len Lye’s abstract films (although Charters wouldn’t have known them, back then). The main-drag sequence is a montage, where images pile up so fast that, at points, it looks like the film has been double-exposed. The final sequence, in which the abandoned girl pathetically eyes herself in the mirror, is expressionist, like some Maya Deren psychodrama.

Film Exercise is not only Charters’s first film, it’s probably the first film ever made at Elam. It’s remarkably accomplished and precocious, especially considering there barely was a film industry in New Zealand at the time. After it was shown at the Sydney Film Festival in 1967, it earned Charters a place in the new film school at London’s Royal College, from which he went on to become a Hollywood cinematographer and director.

In Film Exercise, Charters’s technology was basic—he borrowed his dad’s Bolex—but he was inventive. He used a huge variety of shot types, as if exploring every possible approach. In one sequence, for low-angle tracking shots, he took the door off the Fiat 500 he borrowed from his ad-agency boss Bob Harvey, and, for high angles, he opened its roof. At one point, he even turned the camera upside down, to follow the couple on the bike under a bridge. Much of Film Exercise was shot at night, using fast film and available light.

Synchronised sound was too complicated, so dialogue was out (although Charters did make occasional use of scene-setting diegetic ‘sound effects’ that didn’t require fine synching—waves, revving engine, a traffic-lights buzzer, party hubbub, etc). Instead, the film was cut rhythmically to a tailor-made soundtrack provided by West Auckland’s top rock band, the La De Da’s. Heavy on the guitar and organ, it was all instrumentals, except for one song at the end, ‘Don’t You Stand in My Way’, whose lyrics seem to taunt the abandoned girl, adding insult to injury. Film Exercise feels like an extended music clip. Here, Charters acknowledges two key influences. First, Richard Lester’s Beatles film A Hard Day’s Night (1964), which combined a black-and-white cinema verite look with music sequences. Second, the documentary short Snow (1963), by director Geoffrey Jones, with cinematographer Wolfgang Suschitzky, which his Elam photography lecturer Tom Hutchins had shown him. Made for British Transport Films, it showed trains ploughing through snow, edited to the accelerating tempo of a cover version of Sandy Nelson’s 1959 hit rock instrumental ‘Teen Beat’.

Today, half a century on, Film Exercise has social-history appeal. It offers a picaresque cross-section of the city, passing from nature to culture, and from the public space of Queen Street to a private home. The main-drag sequence is remarkable for its kaleidoscopic presentation of pedestrian crossings, shops, and burger bars, neons and flashing lights, with Charters contrasting oldies (an office worker and a prune-faced pensioner) with the young ones (groovers in long hair and striped suits, chicks in miniskirts and berets). And, in the final sequence, it’s fascinating to see how art students partied, swigging beer from big brown bottles, in front of unframed expressionist paintings. The way we were.

•

At the end of 1962, after graduating from art school in Christchurch, Gary Baigent drove his motorbike to Auckland. There, he worked part time as a labourer and wharfie to make ends meet and took photographs. He was a ‘street photographer’, carrying a 35mm camera with him and shooting scenes he encountered, documenting close friends and total strangers. He later described his 1960s Auckland as ‘a large number of houses spread about Grafton, Parnell, Mount Eden and Ponsonby, all filled with students, artists, pseudo-intellectuals, layabouts and bums, both bohemian and hobohemian’.8

Taken over a three-year period, The Unseen City’s images capture Aucklanders at work and at play. Baigent avoided the beautiful and picturesque, preferring to dwell on bleak, neglected aspects of the city.9 He used fast film and pushed it, and printed on hard photographic papers, achieving a contrasty, grainy look. The book includes many ‘bad’ photographs: double-exposed, underexposed, or shot facing the sun. Images of ruin and decay seem to echo Baigent’s attitude to technique. A shot of the head of a bum, passed out, is so illegible that the photographer might himself have been drunk. (I had to go to the illustration list to identify the subject.) Like Charters, Baigent contrasts straights and hipsters, speaking to the emerging generation gap. One image is of a (presumably bewildered) old man looking at some risqué Pat Hanly Figures in Light paintings in Auckland City Art Gallery. Its tongue-in-cheek title—Hanly Admirer. Other images feature youthful revellers and thoughtful beatniks.

Bernard Hill described the Auckland of The Unseen City as ‘an unusual, unexpectedly exotic metropolis’, noting that Baigent’s photos ‘create beauty and design or high drama out of the city’s marked ugliness’.10 The book is bewilderingly random—a mix of the poetic and the banal, the artsy and the casual. There is no narrative, no logic to the sequence. Images move from style to style, site to site, and subject to subject without rhyme or reason, perhaps evoking the way one loses oneself in a city, experiencing fragmentary ‘chance’ encounters. Subsequent commentators have observed echoes of other photographers, like Walker Evans, Robert Frank, Bruce Davidson, and William Klein, but Baigent hardly knew their works then, except for a few shots of Frank’s and Davidson’s in Esquire magazines. It would be years before he would see Frank’s 1958 book The Americans. Filmmakers were more influential, particularly the gritty hand-held and night photography of John Cassavetes’s Shadows (1959).

Tom Hutchins criticised The Unseen City for ‘mistaking a highly restricted fringe world of decay, social isolation and a kind of scruffy freedom as the only arena of urban life’.11 Certainly, the book was addressed to those sympathetic with Baigent’s down-at-heel, warts-and-all view of the city. It was quickly identified as an antidote to classy ‘beautiful New Zealand’ coffee-table books, with their quality reproductions and texts by eminent novelists and poets. These were exemplified by painter Peter McIntyre’s 1964 book Peter McIntyre’s New Zealand (whose first edition sold out in six days and which remained in print for twenty years), and by the new photobooks, particularly Kenneth and Jean Bigwood’s New Zealand in Colour (1961), with its text by poet James K. Baxter (over 120,000 copies sold), and Brian Brake’s New Zealand: Gift of the Sea (1963), with words by novelist Maurice Shadbolt.12 While the Bigwoods and Brake books argued the artsy status of photography, Baigent rejected eye candy and supplementary prose (although, early on, Brian Roche had been lined up to write).

The Unseen City was criticised for its careless photography and sloppy production. It was printed on cheap, uncoated paper, which flattened contrast and suppressed detail (many images were already blown-up details, not full frames). Betraying their conservatism, other photographers proved to be Baigent’s harshest critics. In the Auckland Star, Hutchins despaired, ‘Mr Baigent could be too important a photographer not to learn photography.’13 In New Zealand Camera, Frank Hofmann also decried Baigent’s lack of craft.14 In Craccum, Max Oettli wrote: ‘… Mr Baigent worked at a double disadvantage. Firstly he lacked the technical competence to produce good photographs consistently, and secondly his publishers appear to have failed to find a printer who could make adequate reproductions of the pictures.’15 But, even Baigent’s critics recognised his audacity.

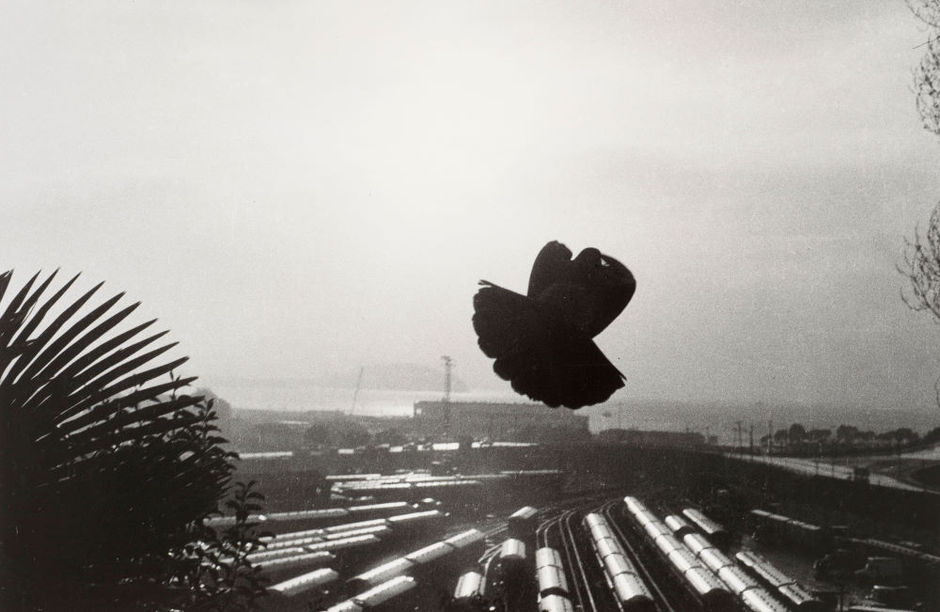

Today, everything about The Unseen City seems classic. The bad printing and paper seem perfect for Baigent’s aesthetic and subject matter. It’s hard to imagine the book being different. But it could have been. Originally, Baigent planned to call it ‘Eyes in a City’ and he wanted the cover image to be a shot he had made through a car’s dirty windscreen. The publishers had other ideas. As a title, they preferred ‘The Unseen City’, and, for the cover, they picked a quintessential ‘bad’ photograph—a pigeon, reduced to an incoherent silhouette, flying over railway yards, against a grey sky. Countering the pop-romanticism of Don Binney’s harsh-lit bird paintings, Pigeon, Parnell became iconic, coming to stand for Baigent’s whole project, while the dirty-windscreen shot was dropped from the project entirely.

Now, The Unseen City looks conventional. This is, arguably, a mark of its influence. At the time, it was new. Its publication coincided with the New Zealand release of Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1966 film Blow-Up, which helped make street photography cool. In the 1970s, street photography would become a dominant idiom in New Zealand art photography. But Baigent got there first.

.

Back in the day, Auckland was still small and intimate. People knew one another. At Elam, Charters was taught by Ellis, and he went on to study at the Royal College, where Ellis had trained. In his 1987 Metro article on The Unseen City, Baigent name checks Charters and Ellis, among others.16 Doubtless, all three crossed paths in the Kiwi Tavern, but none of them were close. While this show might seem to describe a particular milieu, in fact the artists approached their city from very different directions. Born in 1929, Ellis was already an establishment figure—a key New Zealand painter. Born in 1941 and 1945 respectively, Baigent and Charters were outside the art world proper—photography and film were not yet part of that discussion (Alternative Cinema wouldn’t be formed until 1972 and PhotoForum until 1973). Charters was on a trajectory to be part of the film industry, while Baigent was living a hand-to-mouth existence. Their works reflect that difference. It is telling to view Film Exercise alongside The Unseen City. Despite the clear parallels in imagery and treatment, they are radically different in feel. Film Exercise is jaunty—it looks like advertising or a music clip. The Unseen City is disorienting, melancholy, and politically conscious—embracing aspects of working-class life and protest culture.

This exhibition sets out to recover the conjunction and the disjunction of these three artists’ attitudes, and to consider how they triangulate the now-lost city of Auckland.

.

[IMAGE: Gary Baigent Pigeon, Parnell 1965]

_

- From the dust-jacket blurb. Gary Baigent, The Unseen City: 123 Photographs of Auckland (Auckland and San Francisco: Blackwood and Janet Paul and Tri-Ocean Books, 1967).

- Some of these drawings were first shown in Ellis’s 2014 Auckland Art Gallery retrospective, Turangawaewae: A Place to Stand; others are shown here for the first time. Ellis’s Motorway paintings develop out of his City paintings, which were partly inspired by a visit to Spain. In practice, it is often hard to distinguish City and Motorway works.

- Auckland celebrated passing the half-million population mark with a street parade on 10 July 1964.

- Robert Ellis (Auckland: Ron Sang Publications, 2014), 285.

- In the catalogue that accompanied Ellis’s 1965 show at Auckland’s Barry Lett Galleries, Hamish Keith took a negative view: ‘… the city in which we live, as young and small as it is, already demonstrates the seeds of its eventual corruption. A hardening, as it were, of the urban arteries.’ More recently, he wrote: ‘The Auckland to which Robert returned was being gutted. The city had caught the car-borne disease of endless sprawl. Some nine hundred houses had been ripped out of the inner suburbs of Newton, Grafton, and Arch Hill. One of those houses was the crumbling cottage I shared with Barry Brickell and, a little later, Graham Percy, one of Robert’s brighter students. To us the character of Auckland was being destroyed—Robert took a more positive view. He had learnt to drive. He had a small car. To him the burgeoning motorway was a new and stimulating mobility.’ Hamish Keith, ‘The Ambassadors’, in Robert Ellis (Auckland: Ron Sang Publications, 2014), 18.

- Even those occasional koru forms in the Motorway paintings could be topographical features from elsewhere on the planet. In the 1970s, Ellis incorporated motorway imagery into more geographically specific paintings, such as his Te Rawhiti series (1974–5) and his Auckland International Airport mural, North Auckland Itinerary (1977–8).

- In the early 1970s, Gary Baigent went off the grid for a spell , living in Te Rawhiti. He would write, ‘Formerly the rates had been too high for many of the local people, but after the road reached Hauai, and with evidence that it would soon reach Kaimaramara, the rates had all increased along with the land values. Although some were happy to sell for a good profit, others who didn’t were forced to anyway because they couldn’t afford the new rates. It was something of a Catch-22 situation.’ Gary Baigent, ‘Rawhiti: Before the Road’, Metro, September 1987: 153.

- Gary Baigent, ‘Hobohemia: Making The Unseen City’, Metro, December 1987: 236.

- For a view of Auckland as modern and progressive, see the short documentary, This Auckland (dir. Hugh Macdonald, 1967). www.nzonscreen.com/title/this-auckland-1967.

- Bernard Hill, ‘Eve’s Special Book Review: The Unseen City’, Eve, November 1967: 55.

- Robert (Tom) Hutchins, ‘Struggle of Issues in 40 Photographs of the City’, Auckland Star, 13 October 1967.

- Baigent did like some New Zealand photobooks, including Jane and Bernie Hill’s Hey Boy! (1962) and Les Cleveland’s The Silent Land (1966).

- Robert (Tom) Hutchins, ‘Struggle of Issues in 40 Photographs of the City’.

- Frank Hofmann, ‘The Unseen City’, New Zealand Camera, June 1968: 23.

- Craccum, 29 April 1968.

- Gary Baigent, ‘Hobohemia: Making The Unseen City’: 239, 241.