Cindy Sherman, ex. cat. (Brisbane: Queensland Art Gallery, 2016).

For me, Cindy Sherman’s work has always been there. I first encountered it as an impressionable undergrad at the University of Auckland in the early 1980s. Back then, feminism was changing the shape of my art-history courses. The department had just introduced a women-in-art paper, and revisionist lectures on women artists and on the depiction of women in art were being introduced into other papers. Images by women were celebrated; images of women were critiqued. Sherman’s work belonged to that Zeitgeist, plus it was a game changer.

Here, in New Zealand, Sherman’s work was a breath of fresh air. It was an antidote to all the women’s-art-movement art that was countering ‘dominant’ images of women with equally prescriptive images of goddesses and matriarchs, tides and lunar cycles, shells and spirals.1 Sherman’s work made that neo-pagan work look like a fanciful retreat from reality—and rather essentialist. Her reference points, back then, were more immediate, more contemporary, more real world—pop culture, the movies.

Feminist critics celebrated Sherman’s early work—the Untitled Film Stills (1977–80), Rear-Screen Projections (1980), and Centerfolds (1980-1)—as female ‘masquerade’. That idea had been in the ether since 1929, when the British psychoanalyst Joan Riviere published ‘Womanliness as a Masquerade’.2 Her paper prompted us to understand that women play at being women, that femininity is a mask, a projection, a put-on. Women are, of necessity, actors—female impersonators, role-players. For better or worse, gender is performance. Sherman’s champions argued that she confounded prescribed femininities not by offering alternatives, but by foregrounding the artifice, emphasising the charade. The argument turned on the assumption that Sherman had agency, which meant she was not simply exemplifying a female condition, but, in the process, somehow undoing it, through self-consciousness, reflexivity. Masquerade had become the solution as well as the problem.

As a young man with feminist pretensions, I gravitated towards Sherman’s early work. I could recite the arguments for it, chapter and verse. But, at the same time, I did enjoy seeing Sherman play ‘The Girl’, as Arthur Danto put it.3 I loved her in her would-be starlet, ingenue, heroine and damsel-in-distress roles. She was sexy and her role-play felt coy. Female masquerade granted her a licence to confound the male gaze, but also an excuse to court it. And it was a get-out-of-jail-free card for the viewer, too. It let me take my voyeuristic pleasure with a righteous alibi. I could compartmentalise, revelling by turns in the work’s critique and in its complicity. I doubt I was alone in my bad faith.4

In retrospect, it is hard to know why the idea of female-masquerade-as-critique had such traction or seemed to be such a revelation. After all, female movie stars can play a range of characters without rocking the boat. We appreciate their compelling performances without losing sight of the fact that it’s them performing—it’s called acting. So, why should acting be uncritical in the movies (generating problematic stereotypes), but suddenly insightful when transposed into photography, into art (now supposedly undermining the exact same stereotypes)? And why was female thespianism necessarily feminist? Surely, it could have equally been framed by the old misogynistic idea of the femme fatale—the woman as alluring and calculating, duplicitous and deadly.

Not everyone read Sherman’s works as feminist, least of all the artist.5 She distanced herself from big-picture feminist positioning, preferring to discuss her work anecdotally, in terms of her processes and the characters she created, describing them as, say, ‘sexy earth mama’ or ‘retired realtor’.6 Magazine profiles explained that Sherman had played dress-ups obsessively since childhood, suggesting she had essentially transposed her compulsion into her art.

So did Sherman’s work critique the female condition or simply exemplify it? Was the critique coming from the work or being projected onto it? It was difficult to tell. But, it was this very ambiguity that proved so engaging. Sherman’s work always was a line call.

In the mid 1980s, Sherman shifted gear. She backed away from appealing media stereotypes. She went darker. Her characters started to look more like frumps, weirdos, bag ladies, vampires, and trolls. Grotesque, they did not embody any agreeable feminine ideal, but the opposite. They evoked women’s inability or refusal to live up to the ideal—to ‘pass’ as women. If Sherman was masquerading still, it was as characters who had trouble masquerading as women. The idea of female masquerade had to stretch. On the occasion of her 1989 show at Wellington’s Shed 11, critic Lita Barrie explained: ‘Sherman’s work covers all the permutations of the fictions man has created around women’s identity, from his most desirable turn-on to his most undesirable turn-off.’7

Where once she had appealed, Sherman increasingly sought to alienate her fans. In a 2012 interview, she admitted as much: ‘That’s what inspired the pictures with vomit and all that. Because I thought to myself, “Well, they think it’s all cute with the costumes and makeup, let’s see if they put this above their couch.” And it worked, they didn’t. It took a long time for that stuff to be accepted, much less sought after.’8

In the 1990s, Sherman’s work took a series of nasty and X-rated turns. For a while, she even jettisoned her signature idea, exiling herself from her pictures in favour of mannequins and prostheses. The dreamy Sherman of the late 1970s and early 1980s was gone.

.

One of the most influential artists of her generation, Sherman’s work has been catnip for theorists and a hit with audiences. It has prompted sustained academic inquiry and entered the popular imagination. It has inspired legions of followers and dredged up endless precedents, reshaping art history, forward and back.9

Sherman has participated in and survived numerous art world paradigm shifts. In the beginning, she was a key figure in the ‘Pictures’ generation of American postmodernists and instrumental in art photography’s ‘directorial’ turn. Her example inspired a phalanx of women art students, making coquettish critiques of the male gaze a staple of art school exhibitions. Later, her Disasters series (1986–9) resonated with the works of philosopher Julia Kristeva and librarian-surrealist pornographer Georges Bataille and participated in the rise of abject art. Then, her Sex Pictures (1992) invaded the uncanny valley and surfed the creepy mannequin-art wave. Although her work was promoted as a critique of mainstream codes, she directed a feature film, featuring Molly Ringwald, and got even deeper into bed with the fashion industry.10 Paradoxically, her work would provide a blueprint for identity art; Sherman’s masquerade inspiring artists who wanted to assert their identity (revelling in their otherness), as well as those who wanted to sidestep it. The biennales are now awash with the work of gay and queer Shermanettes, postcolonial Shermanettes and outsider-art Shermanettes. Sherman has always been everything and its opposite.

Sherman changed the landscape, but kept sexist stereotypes in play. Her ironic appropriation was ambivalent. As a form of criticism, it placed problematic images at arm’s length; as a mode of affection, it kept them within arm’s reach. And her timing was impeccable. A decade before Madonna’s clip for ‘Vogue’ (1990) and her book Sex (1992), Sherman had already opened up space for an alternative response to prescriptive images, allowing women to robustly engage with stereotypes and other received wisdoms. Her role-play anticipated and legitimised Madonna’s (they both made themselves over as Marilyn Monroe). Guilty pleasures! Sexy feminism! Girl power! Madonna can’t have missed this. She sponsored Sherman’s 1997 Museum of Modern Art show, The Complete Untitled Film Stills. Perfect brand alignment.

Since then, feminism and sexism have become even more hopelessly entangled. Empowered, autonomous females have become idealised male sex objects—Tomb Raider’s Lara Croft is the boy gamer’s wet dream. Meanwhile, the Fifty Shades of Grey books have sold over 125 million copies in 50-plus languages—women the world over romancing their chains. Feminism’s moral compass is spinning and feminist art has become Janus-faced, embracing radically conflicting and conflicted approaches. Feminist art can now be confessional and true, or coy and duplicitous. It can deny gender as a social construct or assert it as fundamental. It can embrace femininity or repudiate it. It can align women with nature or reject the idea as sexist. It can rail against pornography and prostitution or endorse them. It can attack middle-class values as patriarchal (preferring the transgressive) or celebrate decorum (as if genteel middle-class refinement was always already feminist).

As one woman’s feminism is now always another’s anti-feminism, is it meaningful to even argue whether Sherman’s work is feminist or not? Perhaps, feminism in art today is less about the side you take and more about what you take sides over—a set of common questions rather than common answers. This would make the ambivalent Sherman the exemplary meta-feminist.

.

There have been other big Sherman survey exhibitions recently, but this show is different. It only presents work made since 2000, after Sherman returned to photographing herself. While it leaves out much that her reputation is founded on, it prompts us to consider how Sherman’s work and the world around it have changed, and how her recent images build on or transcend the readings established for her work last century. Two things strike me: Sherman’s work now belongs less to feminism and more to caricature, and her relationship to ‘the background’—and, with it, the world—is a new focus.

.

Our attitudes to gender have changed. On the one hand, with the rise of genetics, we are less likely to insist that gender is simply a cultural construct—the bedrock of much 1980s feminism. On the other, we have thoroughly absorbed the female masquerade argument that greased the reception of Sherman’s early work. Thanks to her, it has become a truism, not an argument anyone now needs to make.

Sherman’s relationship to the idea of female masquerade has also changed. In her Clowns series (2003–4), she poses before lurid colour swirls and smears, and amid psychedelic atmospheres and vortexes. She presents herself as a shudder of clowns, part fun, part demented.11 These works play on a common fear of clowns (coulrophobia). With their exaggerated facial features, monstrous body parts and sadistic tendencies, clowns are creepy—not sexy.12 They are outsiders, psycho-lepers, with no social buy-in. Because of this, they are also threatening. Sherman’s clowns could be masochistic victims or sadistic villains, or each masquerading as the other.

These images recall others where Sherman portrayed excessively made-up and/or inanely dressed women, women who do not convincingly convey a ‘natural’ femininity. Clown women! Indeed, Sherman’s clowns look more-or-less like men. It is as though Joan Riviere’s feminine mask has fallen away and this is what is left behind—women as men, but not even proper men, clowns. Sherman’s clown-women may be isolated through their inability to make the grade, but perhaps this also relieves them of having to buy into dominant norms. Are her clowns emblems of pathetic marginality or of sociopathic empowerment—like the vengeful carnival performers in Tod Browning’s 1932 film Freaks, who mutilate the beautiful, but despicable, trapeze artist Cleopatra?

It is telling to compare Sherman’s ‘clowns’ with her later series Society Portraits (2008). Sherman demonstrates her powers of observation in these detailed studies of older, high-maintenance trophy wives and trophy widows, who are Botoxed, nip-tucked and attired to the max. These ‘ladies who lunch’ might even be art collectors—Sherman’s target market or not. Their regal ilk will be familiar to anyone who views the fashion blog Advanced Style with smug amusement, with deep admiration, or for its gerontophile appeal.13

Preoccupied with their status and sophistication, these ‘women of a certain age’ are at war with the clock. Ranging from elegant to freaky, these staged portraits appear to have been taken by a specialist professional photographer versed in the photographic art of flattery, with a bag of tricks derived from old-school portrait painting, as well as from photography. But the cracks show through. Is this social critique or misogynistic, menopausal humour? If clowns are excluded, aren’t these privileged insiders equally excluded—disqualified by age? Are they analogous to clowns—funny because they are failures? The designer of the Museum of Modern Art’s 2012 Cindy Sherman catalogue may have thought so; on the back cover, the faces of a Sherman clown and a Sherman socialite are spliced together.

Sherman’s typology of botched and unruly females is inclusive, running the class gamut from Walmart weirdos to socialites. No sector seems spared. Isolated from the arguments that orbited her early work (which now go without saying), twenty-first-century Sherman belongs less to feminism and more to caricature. She is part of a tradition stretching from Leonardo da Vinci and Albrecht Dürer through William Hogarth, James Gillray, Honoré Daumier, and Pablo Picasso to her contemporaries Robert Crumb, George Condo, and John Currin. With their love of exaggeration and deformity, caricaturists have endlessly poked fun at baseness and social pretensions, lack of style and fickle fashions, laughing at those both less fortunate and more fortunate than themselves (or ourselves). Their work typically implies another image, a normative or ideal image, to be mocked and overturned.

At its most misanthropic, caricature finds us all vain and venal, fatuous and wanting, but, at its most humanistic, it prompts us to try to understand and accept our foibles and those of others. But, where does Sherman’s work sit in this continuum? Is she cruel or kind? Or is she being cruel to be kind? Blending schadenfreude and sympathy, Sherman makes that a tough question to answer.

.

In this new century, digital photography has transformed the way Sherman makes her images and our expectations of them. Photoshop allows her to tweak her facial features, like digital putty. Sherman previously shot images of herself in sets constructed in the studio—actress and scenario were all of a piece, so to speak. Now, she captures herself against a green screen, then composites herself into backgrounds. Using her computer, Sherman can, at her leisure, try on different backgrounds for size, like clothes or accessories, looking for the perfect match, or mismatch. This also means her backgrounds can be more elaborate—landscapes, even. In recent work, there is a new exploration of her relationship to the background, to the world—the not-me.

This becomes explicit in the Murals (2010–ongoing), which emphasise the compositing process. These works feature black-and-white landscapes, which Sherman shot in New York’s Central Park. The scenes do not fill the frame. They are symmetrical and mirrored like Rorschach-test blots, as if the artist were double daring us to project our own emotions onto them. Sherman treated them to suggest old engravings. They also recall painted backdrops from Victorian photography studios.

A cast of Shermans poses before them. Larger than life and in colour, they don’t appear to occupy the landscapes, but look arbitrarily and crudely imposed upon them. Many of their costumes appear to hail from the circus or from an amateur theatre company’s props box. Here, Sherman’s performances are hardly dramatic—rather, they are affectless. One of her characters, wearing an ill-fitting female nude-suit and brandishing a theatre sword, seems a bit bored. The onesie, which Sherman also wore in one of the ‘clowns’ works, signifies sex, but is hardly sexy—more tragic.14 Female masquerade, indeed. The Murals feel unconvincing, their arrangements provisional. There is no synergy between the characters, or between them and the scenery. The figures appear alienated from one another and cut adrift from the world and from us—they are ‘out of context’. The Murals are Sherman’s least affective, most deconstructed works—it is difficult to figure out what was intended. This is their virtue.

The Murals do something new, but they also look back to very early works. They recall Sherman’s collage series A Play of Selves (1975), where cut-out Sherman paper-doll characters are arranged into tableaux. The backgrounds are blank, as if waiting for a real background to be added or imagined. The Murals also recall the Rear-Screen Projections, where Sherman poses, like a heroine from a Hitchcock film, in front of projected backgrounds, where a dramatic change of location would only require loading the projector with a different slide.

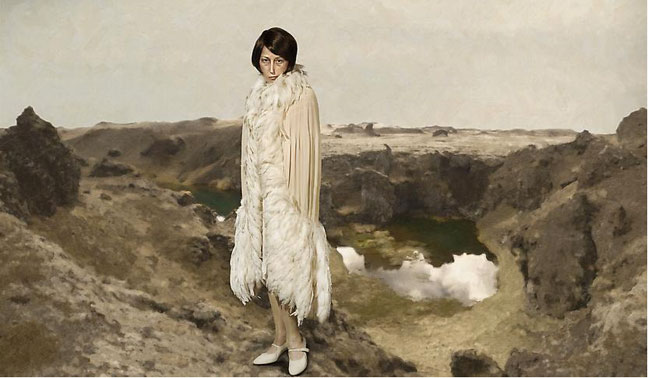

Sherman’s inquiry into the background continues in her Chanel series (2010–2). It had its origins in a 32-page ‘zine-insert’ she made for art collector and magazine editor Dasha Zhukova’s fashion magazine Pop in 2010.15 In it, Sherman modelled a range of eccentric vintage Chanel outfits. Again, she superimposed her characters over landscapes shot separately, some in Iceland during the 2010 volcanic eruption,16 some on Italy’s Isle of Capri. In the magazine, these scenes were presented as shaped backgrounds, as in Murals, emphasising the artifice of the arrangement. Although, this time, they were in colour, were not mirrored, and had roughly scissored outlines with telltale drop shadows. The project confirmed the idea that theme-dressing fashion might allow women to imaginatively transport themselves to exotic, fantasy realms. And yet these beautifully attired women hardly seemed happy.

In the Chanel series, Sherman reworked the images she shot for Pop, but changed the treatment. She kept the faux, painted backdrop look, but expanded the scenery to fill the frame. She processed the photographic backgrounds to look like paintings, with oil painting impasto (a dash of Courbet), or, in one case, dainty watercolour dappling. Evoking ‘real’ art, the effect is at once classy and cheesy. But it’s unconvincing; it looks false. The grating disjunction between the painterly backgrounds and the not-painterly figures disables our suspension of disbelief. In one image, a figure visibly fades out below the waist, making the conceit explicit. Floating like a spectre, the woman was never really there.

In this series, Sherman collages her women into mostly bleak, desolate landscapes. In their haute couture, the women are both matched and mismatched to the scenery; the colours work but the outfits are rather inappropriate for terrain and climate. The Chanel series suggests that staple of romanticism, the pathetic fallacy—arrogantly presuming that the outside world reflects one’s inner state, reducing the world to an accessory. But here that idea is played up as bogus—a trope.

In the Chanel series, Sherman is, in different ways, inside and outside the world, at one and at odds with it—framed by it yet cut adrift. The seams are showing. If Sherman’s early work rested on a nagging rupture between women real and ideal, her recent work plays more on one between figure and ground, self and world. At the heart of these works is an anxiety about being out of place.

Sherman is a cut-out living in a projection.

.

[IMAGE: Cindy Sherman Untitled 512 2010–1]

- Not that this was the only feminist art in town, but sometimes it seemed that way.

- Joan Riviere, ‘Womanliness as a Masquerade’, International Journal of Psychoanalysis, vol. 10, 1929: 303–13.

- Arthur Danto, ‘Photography and Performance: Cindy Sherman’s stills’, in Cindy Sherman: Untitled Film Stills (New York: Rizzoli, 1990): 14.

- Peter Schjeldahl admitted, ‘As a male, I also find these pictures sentimentally, charmingly and sometimes pretty fiercely erotic. I’m in love again with every look at the insecure blonde in the nighttime city. I am responding to Sherman’s knack, shared with many movie actresses, of projecting feminine vulnerability, thereby triggering (masculine) urges to ravish and/or to protect. But it is the frame, with its exciting safety, that makes my response possible’. Peter Schjeldahl, ‘The Oracle of Images’, in Cindy Sherman (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1987), 8.

- For instance, in 1981, Artforum chose not to run the Centerfolds, which Sherman had made for it, arguing that they reinforced negative stereotypes. Also see Courtnee Kendrick, ‘When a “Feminist” Artist Is Not a Feminist: Challenging Cindy Sherman’s Constructed Position in Discourse’, Academia, February 2012,

www.academia.edu/1570280/When_a_feminist_artist_is_not_ a_feminist_Challenging_Cindy_Shermans_Constructed_Position_ in_Discourse. - Wayne Koestenbaum, ‘Fall Gals: Cindy Sherman’, Artforum, September 2000: 150.

- Lita Barrie, ‘Voyeur’s Fallacy’, New Zealand Listener, 27 November 1989: 116.

- In Kenneth Baker, ‘Cindy Sherman: Interview with a Chameleon’, Walker Art Center Magazine, 1 November 2012, <www.walkerart.org/magazine/2012/cindy-sherman-walker-art-center>, viewed 28 December 2015.

- Sherman connects with other figures in photography: the early adopters Hippolyte Bayard, Virginia Oldoini (Countess of Castiglione), and Fred Holland Day; transvestites Marcel Duchamp, Pierre Molinier, and Andy Warhol; surrealists Hans Bellmer and Claude Cahun; feminists Eleanor Antin and Suzy Lake; outsiders Morton Bartlett and Eugene Von Bruenchenhein. She also links up with gays and queers, like Yasumasa Morimura and Anthony Goicolea, and, adding provincial, postcolonial twists, with Samuel Fosso, Christian Thompson, and Ming Wong. In New Zealand, Sherman’s influence was seen in the work of Margaret Dawson, Christine Webster, Yvonne Todd, Shigeyuki Kihara, and others. Sherman’s example underpinned the exhibition Masquerade, at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art, in 2006.

- Sherman’s film Office Killer (1997) starred Carol Kane, Jeanne Tripplehorn, and Molly Ringwald. Sherman has been involved with the fashion industry since, at least, 1983, when she made advertisements for the New York clothing store Dianne B. This century, her engagement with fashion has revved up, with her Balenciaga and Chanel series. In 2011, she was the face of the cosmetic giant MAC’s autumn line. In 2014, she was selected to collaborate on Louis Vuitton’s Celebrating Monogram project to reinterpret the LV monogram.

- A group of clowns is a shudder, an alley or a pratfall.

- For those who saw it, who can forget Brisbane artist Scott Redford’s traumatising art-porno video Clown Fuck Punk (2002–3), which featured in his exhibition Bricks are Heavy, at the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane, in 2006?

- Advanced Style is a sartorial blog featuring seniors photographed on the streets; see http://advancedstyle.blogspot.com.au/.

- Some of the Murals incorporate black-and-beige Shermans into the black-and-beige landscapes.

- Pop, Autumn–Winter 2010.

- The Eyjafjallajökull volcano in southern Iceland erupted in April 2010, disrupting air travel.

.