Brent Harris: Towards the Swamp, ex. cat. (Christchurch: Christchurch Art Gallery, 2019).

.

People have long found meaning in random phenomena, whether it’s accidentally discovering the face of Jesus burnt into their toast or deliberately employing crystal balls to see the future. They project their own psychic contents onto the world and mistake it for the world talking to them—call it finding meaning in the meaningless, call it the pathetic fallacy, call it ‘return to sender’. Of course, artists have played on this endlessly. In the Renaissance, Leonardo da Vinci urged artists to discover their imagery in dirty walls and varicoloured stones. Later, the romantic Victor Hugo conjured castles and creatures from stains and blots. Later still, the surrealists used automatic drawing, frottage, and decalcomania to bypass intentionality and tap the psychosexual unconscious. Melbourne artist Brent Harris puts his own spin on this tradition.

Harris started experimenting with automatic drawing while on a residency in Paris in 1993. He was in a rut—keen to escape the calculated geometric-abstract approach that had become his trademark since making his Stations of the Cross (1989). Looking for new forms, he began making automatic drawings in smudgy charcoal. The absurd imagery that emerged would be elaborated in paintings like Appalling Moment E4 (1994). That painting plays on the way we are programmed to read faces into random forms. It suggests a stylised, cubist-deconstructed elephant face with eyes and a trunk, but the ‘eyes’ could equally belong to different entities, making that trunk rather more penile. You can’t see both possibilities together; the mind insists either/or—the old duck/rabbit thing. Harris continued to make works rhyming orifices and eyes, penises and nipples, recalling those surrealist photographers who looked at bodies close up or from odd angles so they lost legibility and obtained a monstrous ambiguity.

Automatism is the explicit subject of Harris’s Swamp paintings and prints (1999–2001). These hard-edged, two-tone renderings of dribbles represent complex painterly phenomena in a simplified, graphic manner—echoing Roy Lichtenstein’s comic brushstrokes perhaps. The Swamp works play on figure/ground ambiguities, so sometimes it’s unclear what’s the dribble and what’s the negative space it left behind—they seem interchangeable. Suggesting ejaculate or ectoplasm, the dribbles appear to be simultaneously ascending (rising of their own accord) and descending (dragged down by gravity)—emerging from and sinking into the swamp. This randomness quickly resolves into meaning, as we images in the mess: bent-over bodies, legs, genitalia, breasts, bulbous alien heads. A dribble that could be a penis reminds us that penises themselves dribble. Harris’s Swamp works are about how we see images associations onto random phenomena, but, in themselves, they aren’t so random. Harris has tweaked the forms to make them clearly suggestive, surely coaxing similar associations from all who see them. In this, they recall Swiss psychoanalyst Hermann Rorschach’s famous inkblots, which were not so random, but contrived to elicit specific associations.

Automatism is not just a means to generate novel forms, it goes deeper, revealing the personal, betraying the psychological. For Harris, it free-associated him back to a traumatic childhood that had kept him in voluntary exile from his New Zealand homeland. In his Grotesquerie paintings and prints (2001–2), Harris explores family politics, both personal and archetypal. The works feature a horned, devilish, authoritarian father and a faceless, fleshy mother. Here and there, the father devolves into Swamp-like dribble images, including silhouettes, of children perhaps, turning away from him and each other. However, the negative space between them suggests a similar figure in a contradictory pose, needy arms outstretched towards the father; these arms being echoed in the father’s horns. The faceless mother’s coiffure turns into a face (the father’s, perhaps), confirmed here and there by the suggestion of an eye—even in his absence, she cannot shake him off. In some images, the negative space around the mother’s body suggests a suckling mouth. In some images, the father seems to suck on a penis-like protrusion from a limbless, headless body, whose bumps suggest both breasts and testes—or is he exhaling it, like ectoplasm? Father and mother, male and female, balls and breasts, penis and nipple get royally scrambled in child’s-p.o.v. primal-scene confusion. Harris reiterates and morphs forms to generate suggestive scenarios, but also leaves space for us to interpret them, to find our own way in.

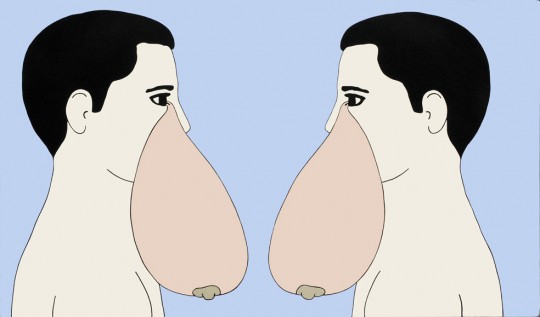

Harris’s works involve a dislocation between content and treatment. In Grotesquerie, heavy personal issues are masked by an impersonal pop style and immaculate flattened-space rendering. Or, as Sarah Thomas characterises it: ‘the cool formality of the artist’s visual language rubbing against the emotional anarchy that helps create it’.1 Harris may use automatism, but he is no expressionist. Expressionists produce works where content and treatment are in sync: Matisse made joyous treatments of joyous subjects while Munch made anguished treatments of anguished ones. Harris is the opposite, routinely exploiting a mismatch between subject and style, thought and feeling. But why? In some works, it certainly provides a psychological arm’s length—insulation, a therapeutic safe space. Take I Weep My Mother’s Breasts (1996), a work exceptional in Harris’s oeuvre and a key to it. It’s perhaps his most overtly autobiographical work, referring to a painful experience: as a child, his father chastised him for nuzzling his mother’s breasts, abruptly ending his easy-going, loving connection with her.2 The painting shows a generic man weeping pendulous breasts—they hang from his eyes like tears. He is repeated on both sides of the canvas, symmetrically, suggesting he is confronting himself doing this, as if in a mirror. But, if there’s pathos in the subject, it’s mysteriously absent in the cool comic treatment. The big twist, however, is that this work is pointedly in the style of another artist, American pop painter John Wesley—a precursor to Harris in fusing surrealism and pop. So, like a ventriloquist, Harris tells the most personal of stories through the voice of another. Quote marks within quote marks. Plausible denial.

Automatic processes have become integrated into Harris’s practice. His work has its more experimental, intuitive phase (making drawings, small painterly studies, and monoprints) and a more refined, deliberate one (making large paintings and editioned prints). Imagery emerges in the experimental phase, where Harris pushes around paint and ink, treating them as scrying tools, conjuring images from the swamp. Of one series, he explains: ‘I was trying to connect psychoanalytic thought, in particular the thinking of Heinz Kohut, with the way I was intuitively finding the imagery. The idea of surrender and catch is that you must “surrender” to what is happening, putting yourself in a position ready to “catch” what is thrown up by the subconscious and the working process—letting things bubble to the surface without too many preconceived ideas prefiguring the outcome.’3 As forms ‘bubble to the surface’, Harris draws them out, sharpens their lines, owns them. Occasionally he’ll seal the deal, by adding eyes to amorphous shapes, making them into heads or faces, giving them an orientation—so we recognise them too.5 Later, he isolates and elaborates his mined and minted motifs in paintings and prints in his graphic style, downplaying the intuitive material process that birthed them. He also transforms his images as he reworks them from painting to painting.

Harris is steeped in art history—preloaded. Images from the canon are ingrained in his conscious/unconscious image repertoire, so it’s no surprise that art-history becomes entangled in his process. Some of his recent series suggest comic-book versions of the old-master narrative paintings we see in museums. Those old paintings were grounded in stories that their viewers were assumed to know—biblical, mythological, literary, historical. But, today, old-master paintings can seem surreal and dreamy because we don’t know their back stories. We see meaningful gestures but don’t know what they mean, and see symbols without knowing what they symbolise. They leave us to wonder. Harris’s works recall our relation to such old-master works, but, unlike them, his works never had a story to begin with. With their echoes of gardens of Eden, Middle-Earth grail quests, and alpinist allegories, they imply a psychic odyssey, but trying to join the dots would be a fool’s errand.

Harris is not a world builder. He’s not one of those artists who elaborates an iconographical system and presides over it knowingly as its master. Instead, like a medium, he intuitively channels images he doesn’t understand and can’t explain. For instance, of the angels in his painting The Other Side (Large) (2015–6), he wrote: ‘I cannot explain their presence, except that they appeared early on and I was unable to move them on … Again they suggested themselves in a few smudges of paint and I quickly sketched them in charcoal, pretty much as they appear.’5 As much as they originate within him, Harris also comes to his images as we do as viewers—as an outsider, a receiver. I’m reminded of Slavoj Žižek observing that the secrets of the ancient Egyptians were also secrets for the ancient Egyptians.7

Harris’s works beg comparison with the supposed automatic-drawing works made by Sydney artist Hany Armanious in the late 1990s. From the embossed surfaces of wallpaper, Armanious famously liberated a sub-orientalist ‘procession of flaxen-headed peasants, timber cutters, and bearded old gentlemen’, as Rex Butler saw it.8 Harris’s Gandalf types perhaps parallel Armanious’s kitschy rustic crew, and both artists use a sentimental storybook-illustration style, but their works are diametrically opposed in effect. Armanious replays surrealist automatism as a ruse, flaunting the unconscious as an alibi, painting ‘automatically’ exactly what he would otherwise, while blaming it all on the embossing. It’s an art joke; there’s no interior inquiry. I’m reminded of Sigmund Freud saying to Salvador Dalí, ‘In classic paintings I look for the unconscious—in a surrealist painting, for the conscious.’9 By contrast, Harris’s current cast of characters may have a similarly whimsical quality, but his inquiry is underpinned by a sincerity that overrides any cliché dimension. Where Armanious was a prankster, Harris—belying all his popist quote marks—is a seeker.

.

[IMAGE Brent Harris I Weep My Mother’s Breasts 1996]

.

- Sarah Thomas, ‘The Passion of Brent Harris’, Just a Feeling: Brent Harris Selected Works 1987–2005 (Melbourne: Ian Potter Museum of Art, 2006), 10.

- ‘I was about eight, and we were driving home from a day at a local beach. I was in the front on my mother’s lap, exhausted, very happily snuggled into her breast. The next thing I knew I was being violently ripped away from this comfort and dragged into the middle of the bench seat, my father bellowing at my mother, “Isn’t he too old for that?” This was the first time my mother’s body had been denied to me and I remember being quite confused. I remember from this point on my mother’s affection was slightly distanced.’ Brent Harris, quoted in Robert Cook, Brent Harris: Swamp Op (Perth: Art Gallery Western Australia, 2006), 24.

- Brent Harris, ‘Brent Harris: Peaks 2015′, https://brentharris.com.au/cms/p/brent-harris–peaks-2015.pdf.

- It’s an old trick, enjoyed by those who apply blind eyes to pet rocks in order to explore their own pathos. American artist Rob Pruitt includes it in his ‘101 Art Ideas You Can Do Yourself’: ‘72. Put googly eyes on things.’ Pop Touched Me: The Art of Rob Pruitt (New York: Abrams, 2010), 48.

- Brent Harris, ‘Brent Harris: The Other Side: A Backroom Project at Tolarno Galleries, March 2016’, https://brentharris.com.au/cms/p/the-other-side-edited-by-mz-2-final.pdf.

- Slavoj Žižek frequently cites this Hegelian dictum. For instance, in The Sublime Object of Ideology (London: Verso, 1989), 178

- Rex Butler, ‘Hany Armanious: The Gift of Sight’, Art and Text, no. 68, 2000: 66.

- Reported by Salvador Dalí in The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí (New York: Dial Press, 1942): 397.