.Art News New Zealand, Autumn 2021.

.

The last time I saw Bill Hammond was at Peter McLeavey’s wake, at Wellington’s Thistle Inn, back in 2015. Even then Hammond was looking frail, so I wasn’t entirely surprised to hear he had died in January, aged seventy-three. I have a bunch of saved-up questions that I will never get to ask him, not that he would have given answers—he never did.

Hammond was an artist of my generation. I was a follower. I witnessed shifts in his work as they occurred, not knowing where he was ultimately headed. I was already a fan of the ‘gritty’, ‘repulsive’ work, before he turned a corner in 1993 and started making the bird-people paintings that everyone loves and that established him as a market darling. I love them too.

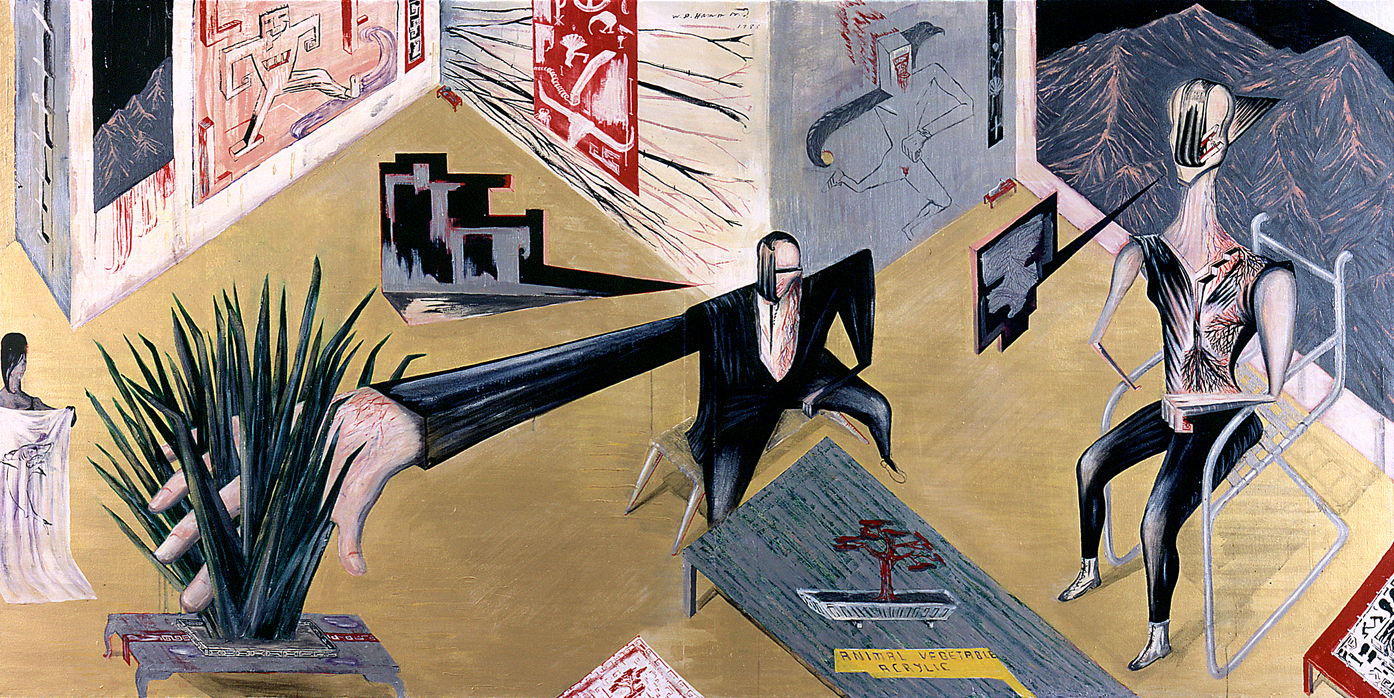

However, my favourite Hammond work will always be Animal Vegetable Acrylic from 1988. I think it’s a key to his whole oeuvre. Painted just after the stock-market crash, this widescreen canvas shows a couple—yuppie collector types—at home in their modernist interior, with their coffee tables and designer chairs. They wear hip clothes with padded shoulders and sport wacky new-romantic haircuts that mask and blind them. Through what seems to be a big picture window, we see a vast, grey mountain range. It’s viewed from an incongruously high angle, apparently at night—the sky is black. This textbook vista recalls those illustrations from Professor Cotton’s Geomorphology of New Zealand, the book that so excited McCahon. A painting of a similar scene also hangs on a wall.

Animal Vegetable Acrylic addresses our alienation, from nature and from each another. For this urbane couple, living in their designer shoebox, nature has become remote and landscape a sign: a view through a window, a painting on a wall. Desperate to reconnect, the man reaches out to run his monstrously enlarged fingers through the spiky leaves of a pot plant—a mother-in-law’s tongue—on a coffee table. A picturesque bonsai—diminished, domesticated nature—rests on another table. Hammond’s title riffs on the twenty-questions game Animal, Vegetable, or Mineral?, but replaces a natural category with an artificial one. Of course, the painting is itself an acrylic.

Animal Vegetable Acrylic is a hot mess, a compendium of visual gimmicks and devilish details. There’s too much to decipher. On the edge of the scene, a vampy, smaller-scale woman holds up a sheet or a towel bearing a shark graphic, like Veronica with her veil. But why? Hammond suggests analogies between things through how they are painted. The veins in the woman’s neck and the man’s hands, and veiny patterns printed on their clothes, echo those in the landscape beyond, as if they might be expressions of the same awesome forces. Or is this a red herring?

This painting is not easy on the eye. Its jarring spaces recall Ames rooms and the isometric perspectives of Japanese prints. The man and the woman inhabit different planes, as if to highlight their emotional disconnection. Their jagged 3D speech bubbles contain no clear messages for one another or for us, just brushstrokes and scribble. Despite this, Hammond wants us to identify with their anxiety and confusion, to connect with them in their inability to connect. They are us.

When we curated Headlands—the big postwar New Zealand art show at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art, back in 1992—we included Animal Vegetable Acrylic as an historical bookend. It was a sign that New Zealanders could no longer fantasise about having a direct romantic relationship with landscape. People got it: a detail from the painting was singled out on the cover of the issue of Art New Zealand that reviewed the show.

Back then, Animal Vegetable Acrylic was owned by venerable blue-chip New Zealand landscape painter Sir Toss Woollaston. That always seemed strange to me, because—besides being roughly the same size and proportions as Woollaston’s big late landscapes—it was the antithesis of Woollaston’s art, stylistically and thematically. Hammond rejected his elder’s earthy colours, love of nature, and bucolic expressivity. He trumped Woollaston. I always wondered why the older artist acquired the painting and what he saw in it. A nail in his art’s coffin, perhaps.

But the painting wasn’t quite the last word that we, the Headlands curators, imagined it was. A year after our show, Hammond started producing the bird-people paintings that would make him world famous in New Zealand and occupied him until the end. These new works emerged from a eureka moment back in 1989. While witnessing the bird life on a trip to the subantarctic Auckland Islands, Hammond imagined he had been transported to a primordial New Zealand, before people, when birds were at the top of the food chain and ruled the roost. It was as if Hammond had made contact with the nature he had previously placed in quote marks.

Joining a tradition of ornithological illustration and bird painting, Hammond’s new works had an undeniable charm. They tapped our romanticism and nationalism, even as they messed with it. His bird-people were floating signifiers. They could be whoever we wanted: us or them. They might stand in for the birds that preceded people, or for Māori, or for Pākehā (in some paintings, they play pool, drink, and smoke). If the bird-people paintings were largely an escapist fantasy conjuring up a mythic past, it was one haunted by future trappings. Its inhabitants were always-already ‘waiting for Buller’.

Hammond flip-flopped, from being an artist centred on modern alienation to one centred on nostalgia and romance. I can’t help but think of him as the opposite of Neo in The Matrix. He started out revelling in a real-world, rat-race, rock’n’roll hell, but took the blue pill and ended up in birdland, communing with Bosch and Bruegel.

I will always read the bird-people paintings through Animal Vegetable Acrylic, as if they picture what’s happening in the head of that modern alienated art collector as he rubs his hand on the leaves of that pot plant in search of a nature fix and is psychically transported to elsewhere and elsewhen, even as his body remains in that hygienic apartment in the here and now. Away with the birds.

.

[IMAGE: Bill Hammond Animal Vegetable Acrylic 1988]