.

Baker Douglas has reproduced Rodney Charters’s photo Woman on a Horse (1966) as a limited-edition poster to support the launch of our Unseen City app book. Not so city, but definitely unseen.

The New Auckland Phonebook

.

I’m a middle-aged art curator, so I’m a hard-copy publishing guy. In the art world, hard-copy publishing is a status thing. Ink on paper in the morning smells like victory. But I’ve just been involved in making an app book and I love it. Baker Douglas has published an expanded app-book version of the catalogue for my 2015 show Unseen City: Gary Baigent, Rodney Charters, and Robert Ellis in Sixties Auckland. The digital format enables the inclusion of different kinds of content and way more content. The show comes to life in a rich new way. The app book includes Rodney Charters’s Film Exercise (1966) as a movie, rather than representing it through stills, and users are guided through Gary Baigent’s photobook The Unseen City (1967) as a movie. There are all kinds of added extras. Everything makes more sense. It leaves the original hard-copy publication for dead. We launch it at Art+Object in Auckland on 30 November, 6–8pm. Join us for the party.

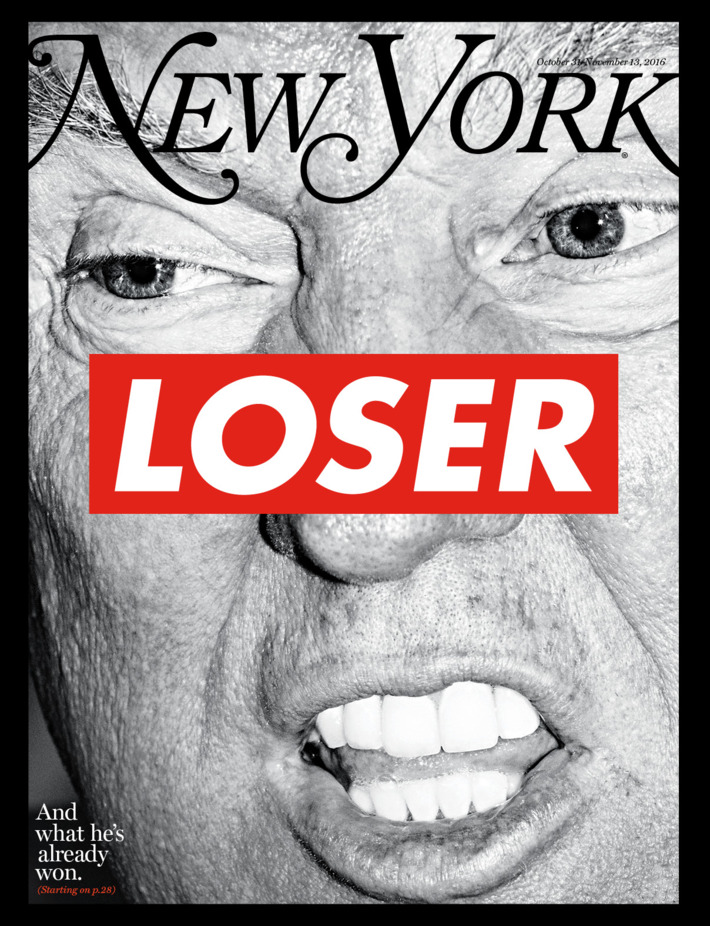

Barbara Kruger, We Presume …

.

Barbara Kruger just designed the cover of New York magazine—her portrait of Donald Trump. I was reminded that, in 1988, Priscilla Pitts, Merylyn Tweedie, and I interviewed the American artist for Antic. Kruger was here for her show at Wellington’s Shed 11. She was a superstar, at the height of her fame, and intellectually intimidating. That’s probably why it took all three of us to interview her. Re-reading the interview, the funniest bit is when Tweedie asks Kruger if she would consider making a film ‘outside the Hollywood system’. Kruger replies: ‘What other system is there? … I don’t want to make a black-and-white film with words over it.’ Presumably, she was unaware that this described Tweedie’s own alternative films to a T. Here’s that interview.

Todd Showing

.

I just attended the opening of Barnacles, photographer Yvonne Todd’s new-work show at Tauranga Art Gallery. It was well worth the trek.

Todd is known for her ‘portraits’ of quirky, imagined female characters, who typically suffer from some or other illness, curse, or blight. Her works draw on the normative language of commercial studio photography, and yet seem persistently askew, perverse, wrong. She uses costumes to help create her characters. In the past, these included vintage gowns she purchased on the Internet (one was a glittering Bob Mackie number, formally owned by a real-life tragedy, Whitney Houston). However, for most of the portraits in Barnacles, Todd designed the outfits herself and had her crafty mum knock them up.

Todd’s new costumes are bizarre. Pale Blue’s robust outfit looks like a straitjacket, with absurd big-mitten hands and bondage-rope detailing. Moone’s oversized quilted bib is like a couture medical collar. Is it to prevent her from hurting herself, to absorb her drool, or both? Infanta wears a repressive Victorian puff-sleeve dress in an incongruously psychedelic paisley pattern. It totally conceals her body: the skirt goes to the floor, the sleeves cover her arms and the collar her neck, and she wears a face mask with the same pattern. It’s hard to know if there’s a real person underneath—the sitter is spectacularly erased. It’s part encasement fetishism, part Kusama-style self-obliteration, with nods to Leigh Bowery and Anatoly Moskvin. Todd’s other portraits are Ernestina (whose appliqué floral dress seems happier than she is) and Amateur Theatre (a glowering, self-styled drama queen).

Todd’s heroines are contradictions in terms. They are glamorous hysterics, ready for their closeups or their ECT.

The new works—we are told—draw on the artist’s recent experience of pregnancy. And one image—smaller than the others, and set off in an egg-shaped frame—presses the point. In Self Portrait (39 Weeks), Todd riffs on those ever-popular pregnancy portraits, where expectant mothers commission professional photographers to celebrate and preserve their most fecund, special moment. But Todd’s version is wacky. She wears a body-hugging, but badly dyed, blue unitard, from which her ripe belly pokes out in contrasting pink, as if visually distinguishing the shape of her own body from that the baby bump. (Perhaps the baby is a ‘barnacle’.) It’s a very flattering image of Todd’s late-pregnancy body, and yet, for such a studio-shot scenario, Todd seems surprisingly un-made-up, and, compared with her five model hysterics, rather plain. For no apparent reason, she holds a pair of glasses.

Todd plays on our desire to interpret, offering us a few hooks, but nothing definitive. On the one hand, Barnacles seems a bit random—a miscellany. On the other hand, it’s tempting to join the dots, to try to find a diagnosis that fits all the symptoms. Can we link the themes of body restraint and body anxiety in Todd’s character portraits to Todd’s own pregnancy?

In addition to the portraits, the show includes two still-life studies: one of a withered old raincoat that looks like a jellyfish, or, perhaps, in this company—we might imagine—a placenta (Augusta); another of a distressed old sack. Perversely, this work is called Sack-Like. But, surely, a sack is not sack like; it is a sack. Is this sack ‘sack-like’ because that’s all there is to it (literally) or to imply that there is more to be said (metaphorically)? By adding this apparently innocuous work with its apparently redundant title, Todd makes me think: sacks are sacks, clothes are sacks, bodies are sacks in sacks, pregnant women are incubation sacks, and images are sack-like—art is pregnant. Todd may be ‘showing’, but she won’t let the cat out of the bag.

(Tauranga Art Gallery, until 6 November 2016; also Fictitious Bodies: Costume in Yvonne Todd’s Photography, Tauranga Art Gallery, until 4 December.)

Highly Recommended

.

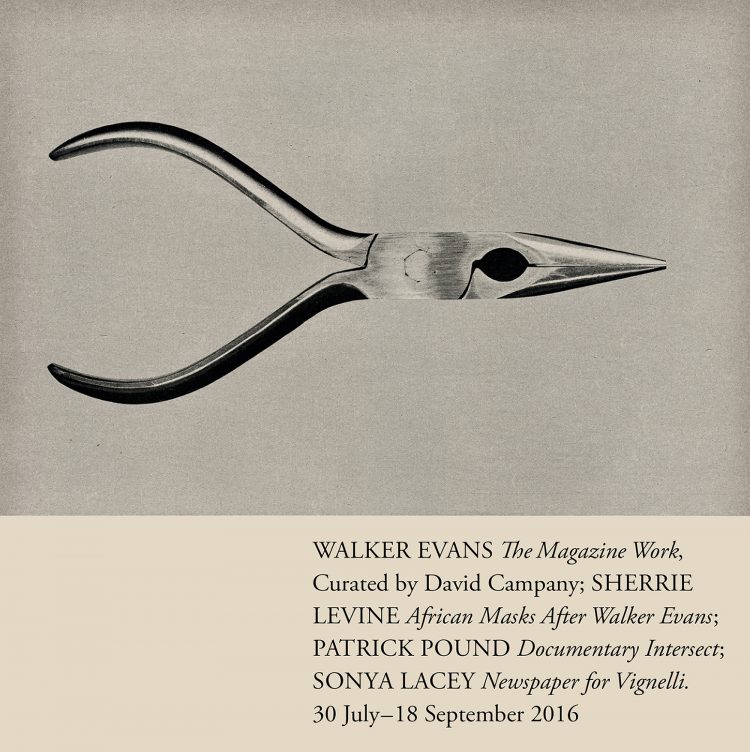

In recent years, Wellington’s Adam Art Gallery has distinguished itself by presenting related shows in counterpoint, in compelling constellations. This has proved a brilliant solution to the constraints of their tiny budget and idiosyncratic spaces. The current mix of shows is smart. Director Tina Barton must be pleased.

The anchor show, Walker Evans: The Magazine Work, has been touring for several years and was clearly a labour of love for British photography curator David Campany. Evans is a canonical figure in American photography, whose career ran from the 1920s to the 1970s. His key images have become icons of art photography and American social history. However, here Campany has approached Evans obliquely, showcasing not these iconic images but the less-known photo-essays he produced for magazines, which often offered a quirky commentary on American life. In assembling his show, Campany rejected the idea of including original prints, preferring to display the actual magazines, which he personally acquired—thanks eBay. Alongside them, he stuck blow-ups of the magazine pages to the gallery walls. Campany’s presentation links and contrasts the logics of the magazine and the exhibition, while cross-referencing his collecting, sorting, and arranging (as curator) with Evans’s (as photographer and artist).

Alongside this main dish, the Adam added three tasting plates: American artist Sherrie Levine’s recent series, African Masks after Walker Evans; New Zealand-born, Melbourne-based Patrick Pound’s project, Documentary Intersect; and local artist Sonya Lacey’s film, Newspaper for Vignelli. Their proximity to the Evans show opens it up in numerous ways.

Levine is synonymous with the idea of appropriation. In 1979, she famously re-produced classic Evans photos of the American South made during the Depression, as if asking: What does it mean for me—as a woman, now—to reiterate these iconic masterpieces? With such gestures, Levine became the art-theory pizza with everything: ‘a feminist hijacking of patriarchal authority, a critique of the commodification of art, and an elegy on the death of modernism’. In 2014, she returned to Evans, reproducing twenty-four photos of African masks from the hundreds he had made in 1935 to document the Museum of Modern Art show African Negro Art. Unlike those images of the South (made around the same time), the Masks are not popularly associated with Evans and seem out of place in his oeuvre. Evans did not make them as (his) art, but as a pay job—of course, one might claim this of his magazine works too. In 2000, his Masks were unearthed in Perfect Documents: Walker Evans and African Art 1935 at the Metropolitan Museum, New York. In 2012, they reappeared in Intense Proximity, the Paris Triennale, curated by Okwui Enwezor, where they kept company with other ethnographic-documents-turned-art, including Claude Lévi-Strauss drawings and a Jean Rouch film. With its Primitivism show in 1984, MOMA was roundly condemned for its bad habit of appropriating primitive art to provide a legitimising context for modernism. By including Evans’s photos in his show, Enwezor located the unwitting photographer within that dodgy history, granting him an authorial role he may well have shrugged. In appropriating the same images in 2014, Levine added a twist, putting all that history into conversation with her earlier appropriations of ‘signature’ Evans images.

Who knows what Evans would have thought of this (or, indeed, of Campany’s treatment of his magazine works)? Of course, it’s irrelevant. Evans’s images have entered the culture and curators and other artists will make of them what they will, reinventing Evans.

Campany is a curator and an artist. His projects often fudge the distinction. So do Patrick Pound’s. Pound makes exhibitions from collections, particularly his own collections. Documentary Intersect links his personal holdings of photos of ‘tears’, ‘floral clocks’, ‘crime scenes’, ‘sleepers’, and San Francisco’s Cliff House. Blu-tacked to the wall in horizontal and vertical lines by category, intersecting on common images, they are like a pictorial crossword. Pound plays on the way images are framed off from one another, yet in dialogue. His mind map intersects with Evans, one of whose photo-essays reproduced a postcard of Cliff House from his own collection (Pound tracked down and included a copy of the very same card). While Pound speaks to this arcane detail within Campany’s Evans project, it also speaks to Evans’s and Campany’s enterprises in general—to Evans’s postcard collecting and to Campany, following him, tracking down all those magazines, joining dots, putting twos and twos together. Foregrounding the collectors-curators’ mindset (or pathology), Pound suggests that they are akin to photographers, as taking photos is essentially a form of collecting—of curating—the world. Of course, this is also a conceit, drawing attention to the Adam’s own curatorial gambit, in forming this precise cluster of shows. Curating about curating.

In her retro-looking black-and-white 16mm film Newspaper for Vignelli, Sonya Lacey chases newspaper pages as they are blown across the ground by the wind, like mass-media tumbleweeds. (It reminds me of that poignant scene in American Beauty, where, in a courtship ritual, a boy and girl watch a video of a plastic bag magically dancing, buffeted by air currents.) But the film is not as casual as it looks and it is not just any newspaper—it is way more contrived. Lacey created the newspaper in question, basing it on Massimo Vignelli’s proposed but unimplemented modernist design for the European Journal of 1978. I’m prompted to read her melancholy film as a key to the Adam’s current ensemble of shows, in which various originals and reiterations find themselves caught up in winds of change, propelled by history, with the Gallery and we viewers, like Lacey, in hot pursuit. The answer, my friend, is blowing in the wind. (Adam Art Gallery, until 18 September).

Ambiguity Is Her Thing

.

We’ve just opened our Francis Upritchard survey show, Jealous Saboteurs. In 1998, after graduating from Ilam School of Fine Arts in Christchurch, Upritchard emigrated to London, where she would become one of New Zealand’s most successful artists. She maintains a close relationship with New Zealand, regularly returning to work and show here.

Upritchard has developed a unique sculptural language. Her works often look like artefacts and museum exhibits. They are rife with allusions to elsewheres and elsewhens. Upritchard interweaves references to archeology and anthropology, to modernism and hippiedom, to nostalgia and futurism. When she represented New Zealand in the Venice Biennale in 2009, she famously explained: ‘I want to create a visionary landscape, which refers to the hallucinatory works of the medieval painters Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel, and simultaneously draws on the utopian rhetoric of post-1960s counterculture, high modernist futurism and the warped dreams of survivalists, millenarians, and social exiles.’

Upritchard’s works combine figurative sculptures, glass and ceramics, found objects, and furniture. She draws on a diversity of art and craft traditions, and often collaborates with artisans. Her most recent sculptures—solitary figures, on metal stands—explore ethnic and cultural types, but remain enigmatic. Are they lovers or fighters, primitives or hippies, wise ones or imbeciles? Are they from then or now—or, indeed, from nowhere and the future? Have they transcended history or has it transcended them? It is hard to know if Upritchard is poking fun at her subjects or taking them seriously. Her aims remain elusive. Ambiguity is her thing.

Jealous Saboteurs is Upritchard’s first survey exhibition. It covers twenty years of work, ranging from little-known art-school works to works produced this year. It’s a joint project with Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne, curated by their Director Charlotte Day and myself. At City Gallery, it runs until 16 October 2016. And there’s a book on the way. (Here’s my essay.)

Blue Period

.

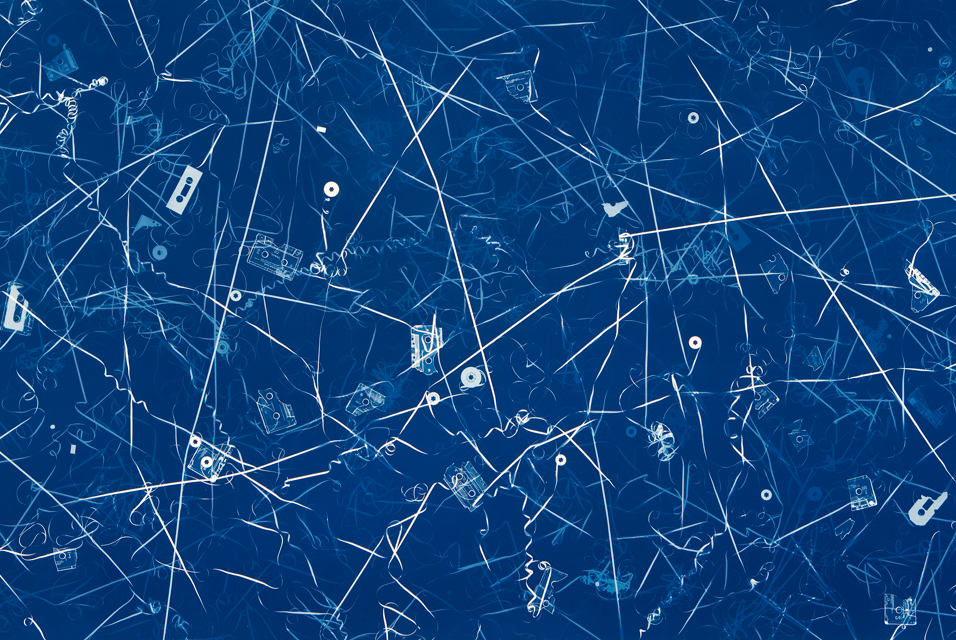

I’ve just spent the weekend on art camp in New Plymouth, attending the opening of the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery’s ambitious new show Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph, curated by Geoff Batchen. My favourite work in it is Swiss artist Christian Marclay’s Allover (Rush, Barbara Streisand, Tina Turner, and Others) (2008). It’s a knockout.

These days, some artists want to be ahead of the curve, negotiating the frontiers of new media, but many more are nostalgic for old media that are past their use-by dates. It has become a genre and the Marclay is a textbook example. He smashed-up audio cassettes—featuring music from Rush, Barbara Streisand, Tina Turner, and others—and spread fragments of their shells and lengths of their magnetic tape across a massive sheet of cyanotype photographic paper, exposed it to light, and developed it. Presto! The gesture piles redundancy upon redundancy, cross-referencing photography, music, and painting.

First, the work is a photogram and a cyanotype. The photogram is a primitive, cameraless form of photography and the cyanotype is an early type of photographic paper. Some of the earliest photos are cyanotypes, including photograms of botanical specimens and contact prints of drawings and graphics. The cyanotype survived, for a long time, as a means to reproduce architectural drawings (blueprints) and for proofing film for offset printing, but, today, it is little use to anyone.

Second, the ostensible subject—the audio cassette—is an obsolete analogue music format, redundant in this, our digital age. Landfill. Replacement value zero.

Third, the end result looks like an old Jackson Pollock action painting—it has that scale. Marclay links the Pollock idea—of ‘the brushstroke’ as a trace or record of the painter’s performance—with the way musical performances are recorded on tape. The work is paradoxical: Pollock was all about direct, unmediated expression (now a discredited, redundant idea), and yet Marclay foregrounds the detritus of mediation.

The now-retro recorded musics of Rush, Streisand, and Turner may be somehow registered here, but as ghosts—inaudible and indistinguishable. Marclay’s haunting, elegiac image suggests the streamers and rubbish left behind after a parade, reminding us that photography is a graveyard, the ultimate memorial medium. Go to New Plymouth, read it and weep. (Until 14 August.)

Bullet Time

My new show, Bullet Time, showcases the work of two New Zealand video artists who conjure with time—Daniel Crooks and Steve Carr. It places them in the context of two historical photographers, pioneers of motion studies—Eadweard Muybridge (1830–1904) and Harold Edgerton (1903–90)—acknowledging them as precursors, influences and reference points. In the process, it engages a complex history of interaction between science and art, photography and cinema, technology and consciousness, thought and feeling.

The show’s title comes from the cinema special-effect made famous by The Matrix (1999). For ‘bullet time’ effects, a set of still cameras surrounding a subject are fired simultaneously or almost simultaneously. Compiled as a movie, the shots offer an orbiting view of the subject, either frozen in time or in super-slow motion, messing with our sense of space and time.

The Matrix’s bullet-time effects looked back to the work of Eadweard Muybridge. In the nineteenth century, there was much debate about whether a horse’s hooves all come off the ground at once during the gait. It occurred too fast to see with the naked eye. The former Californian Governor, railways magnate, and racehorse breeder Leland Stanford engaged Muybridge, the photographer, to furnish evidence to settle the matter. Using a bank of cameras with fast shutters triggered by trip wires, he captured a succession of images of a horse in full stride, proving the theory of ‘unsupported transit’. These images forever changed the way we see horses and led to the development of the cinema.

Based in Melbourne, Daniel Crooks generates bewildering time-space warps by rearranging slivers of digital video information. His Time Slice works look back to Muybridge and to the slit-scan photography used for racetrack photofinishes, and nod to the metaphors used to explain relativity.

At Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in the 1930s, Harold Edgerton pioneered the use of stroboscopic flash photography to study motion. He froze running water, splashes of milk, athletes in action, bullets ripping through balloons, apples, bananas, and playing cards, and exploding atomic bombs. While his work revealed scientific truths, it often had a spectacular, erotic aspect.

Riffing on Edgerton, Steve Carr uses slow-motion to observe bursting paint-filled balloons and bullets tearing open apples. He’s less interested in the scientific aspect than the semiological one. Bullet Time also includes his six-channel video installation Transpiration (2014). Filmed with a time-lapse camera, white carnations planted in dyed water slowly absorb its hues, blushing with colour. (City Gallery Wellington, 25 March–10 July 2016.) (Here’s my essay.)

The Art of Friendship

.

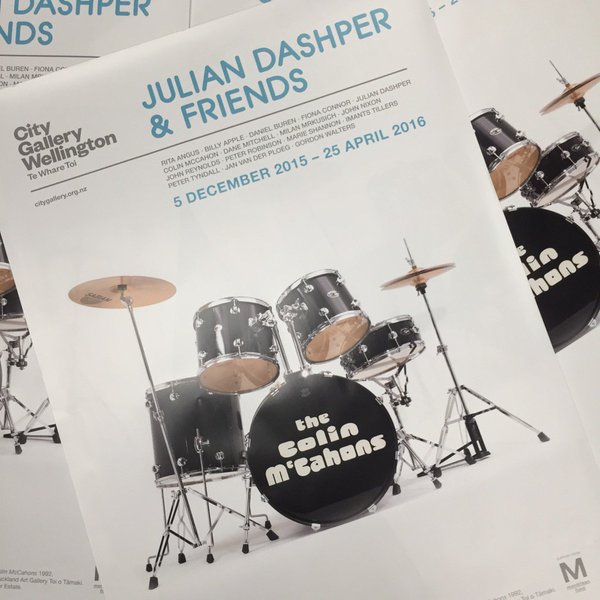

Julian Dashper has been a key figure in New Zealand art since the mid-1980s. He changed the way we think about New Zealand art history. Dashper made art about art. Some of his works pay homage to older celebrated artists, particularly canonical figures of New Zealand art, including Colin McCahon and Rita Angus; others address the workings of the art system. From the mid-1990s, he increasingly exhibited overseas, becoming an international artist. Dashper died of melanoma in 2009—he was just 49. Today, he represents a transitional figure between the ‘New Zealand painting’ that preceded him and the new generation of post-nationalist, post-medium artists that followed.

Dashper was an important artist for me. I can’t think of another artist who has been as influential on my practice as a curator. So, it’s been a huge pleasure to curate the exhibition Julian Dashper & Friends. It’s a tribute show, and, for me, something of a labour of love.

Dashper’s work was self-consciously art historical—it was always in dialogue with other artists’ work. He was one of New Zealand’s most influenced artists and one of its most influential artists. Because of that, I thought that presenting his work in splendid isolation would be confusing, like listening in to one side of a phone conversation. So, instead, my show presents his works in conversation with works by other artists—his elders, his contemporaries, and younger artists. These ‘friends’ include Rita Angus, Billy Apple, Daniel Buren, Fiona Connor, Colin McCahon, Dane Mitchell, Milan Mrkusich, John Nixon, John Reynolds, Peter Robinson, Marie Shannon, Imants Tillers, Peter Tyndall, Jan van der Ploeg, and Gordon Walters. Friendship wasn’t incidental to Dashper’s project, it was his medium. (Julian Dashper & Friends, City Gallery Wellington, 5 December 2015–15 May 2016.) (Here’s my essay and here’s Peter Ireland’s review.)

Imitation, the Sincerest Flattery

.

Wellington art dealer Peter McLeavey is no longer with us, but his legend lives on. Indeed, it grows stronger. Facebook is creaking with tributes, with everyone claiming a connection. McLeavey was a brilliant gallerist, a consummate salesman, a storyteller. It’s hard to imagine New Zealand art without him. In Wellington in the late 1960s and 1970s, he pioneered art dealing—at least, his brand of it. He was influential. Those who followed, especially in Wellington, had to contend with his example, his preeminence.

He had his shtick. Although visitors to his gallery had met him countless times before, McLeavey would sometimes pretend they were strangers. He’d greet them with an odd mix of humility and presumption. He’d say, ‘Hello, my name is Peter McLeavey. I show modern art. I know what the old people think of my gallery. But tell me, what about the young people in the discotheques—what do they think of my gallery?’ When Hamish McKay opened his gallery in Wellington in the early 1990s, he put his own spin on McLeavey’s routine. When people visited his gallery—the young people’s gallery—McKay would say, ‘Hello, my name is Hamish McKay. I show contemporary art. I know what the young people think of my gallery. But tell me, what about the old people on their heart-lung machines—what do they think of my gallery?’

Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. And, with McLeavey, there was much to imitate. His departure creates a vacuum.