.

Last Thursday, as part of City Gallery’s Open Late programme, I chaired a discussion about dolls in art and life. The speakers were artists Yvonne Todd and Ronnie van Hout. We talked a bit about the ‘uncanny valley’, the idea that, as dolls become more and more realistic, they go from being cute to being creepy. I couldn’t resist illustrating the idea with this photo of One Direction posing with their waxworks at Madame Taussauds. Cute and creepy.

The Parallax View

•|

Aaron Lister has curated a lovely satellite exhibition—Other People’s Photographs—to accompany the major Cindy Sherman show currently on display at City Gallery. This sidebar show presents the vernacular photos that Sherman has collected over the years, including a massive haul of snaps taken at Casa Susanna, the now-infamous crossdressers’ retreat in upstate New York. From the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s, men went there to enjoy a vacation from their gender, to become one of the girls. They enacted stereotypical, normative views of femininity, aiming to pass as middle-class housewives, mostly. The snaps are an eye opener, offering an odd perspective on feminism. On the one hand, they anticipate a familiar feminist insight, highlighting femininity as a social construction, a masquerade (a Sherman idea). On the other hand, they complicate feminism, as the men discover their own freedom, release, and agency in the repertoire of characters and gestures, fashions and adornments, that feminists will soon reject. They pad the bras that feminists will burn. But do they retain their male privilege through the process? (City Gallery Wellington, until 19 March.)

Young People Today

When I was young, we thought art was progressing. Everyone was vying to be on the cutting edge, and to define the trajectory of art history. Now art is understood as a network, and people seem more interested in the synchronic fabric of art, how everyone is intersecting—what node you or others are on this web. There seems less at stake; people seem less a part of a greater cause, and more concerned with their own ability to find a niche. On the other hand, artists seem to have much more freedom to carve out their own eccentric territory. There is much greater interest in the world, socially and politically. Art used to be much more about the self: private or archetypal. We used to worry about posterity. Now artists worry about relevance.

—Mernet Larsen, 2016.

Really?

.

‘All Nature faithfully’—But by what feint

Can Nature be subdued to art’s constraint?

Her smallest fragment is still infinite!

And so he paints but what he likes in it.

What does he like? He likes what he can paint!

—Friedrich Nietzsche

Parallel Universe

.

I finally got to see Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party (1974–9), which is now permanently installed in the Brooklyn Museum—that’s one off my bucket list. With its kitschy conflation of ancient and modern, craft and minimalism, this feminist magnum opus reminded me of the Stargate, only triangular. Being installed in a spooky, triangular, black, glass room didn’t hurt.

Mise en Abyme

.

Yesterday I visited Queens Museum to see Mierle Laderman Ukeles’s survey show. Her ‘Manifesto for Maintenance Art’, written in 1969 after the birth of her first child, distinguishes two ‘basic systems’: development (positive feedback—generating change) and maintenance (negative feedback—generating homeostasis, equilibrium). Development, she argues, is celebrated, while maintenance (although crucial) remains unsung and overlooked. A feminist, Ukeles sees that art is identified with ‘development’ and domestic work with ‘maintenance’, even though art involves much maintenance activity. However, by proposing her ‘maintenance art’, she sought to exploit and upset that simple opposition. In 1976, for I Make Maintenance Art One Hour Every Day, she invited 300 custodial workers in a Wall Street office building to designate one hour of their shift as art. In 1979–80, for Touch Sanitation Performance, she traversed New York city for eleven months to shake hands with each of its 8,500 sanitation men, saying ‘Thank you for keeping New York City alive’—a gesture linking class and gender.

For me, Ukeles’s show found its perfect companion in the Panorama of the City of New York, which is on permanent display in the Queens Museum. It’s an incomprehensively massive, 1:1200 scale model of New York’s five boroughs, showing every street, every bridge, every building. Of course, one of those buildings is the Queens Museum itself—it’s a mise en abyme. The Panorama was made for the 1964 New York World’s Fair. Back then, visitors were transported around it on tracked cars (called ‘helicopters’), receiving a recorded audio tour. Those cars have long gone, having been replaced by a pedestrian ramp. In 1993, the model was updated, with subsequent buildings—including the World Trade Centre—added. The Panorama covers 9,335 square feet of the Museum’s floor, rivalling the space taken by Ukeles’s show. (While her show is on, it has been dotted with tiny lights, marking the itinerary of her epic handshake tour.)

From the Panorama’s god’s-eye vantage, New York is an anthill. Looking at it, it’s hard to think of the city as anything but infrastructure—sheer logistics. If Ukeles’s art asserts its maintenance logic down-and-dirty at a personal and gutter level, the Panorama asserts the same thing from above. Perhaps ‘development’ and ‘art’ hover somewhere in between, as the fugitive meat in this high-low sandwich.

Cafe Americain

.

Ilsa: Let’s see, the last time we met …

Rick: Was La Belle Aurore.

How nice, you remembered. But, of course, that was the day the Germans marched into Paris.

Not an easy day to forget.

No.

I remember every detail. The Germans wore gray, you wore blue.

—Casablanca, 1942

.

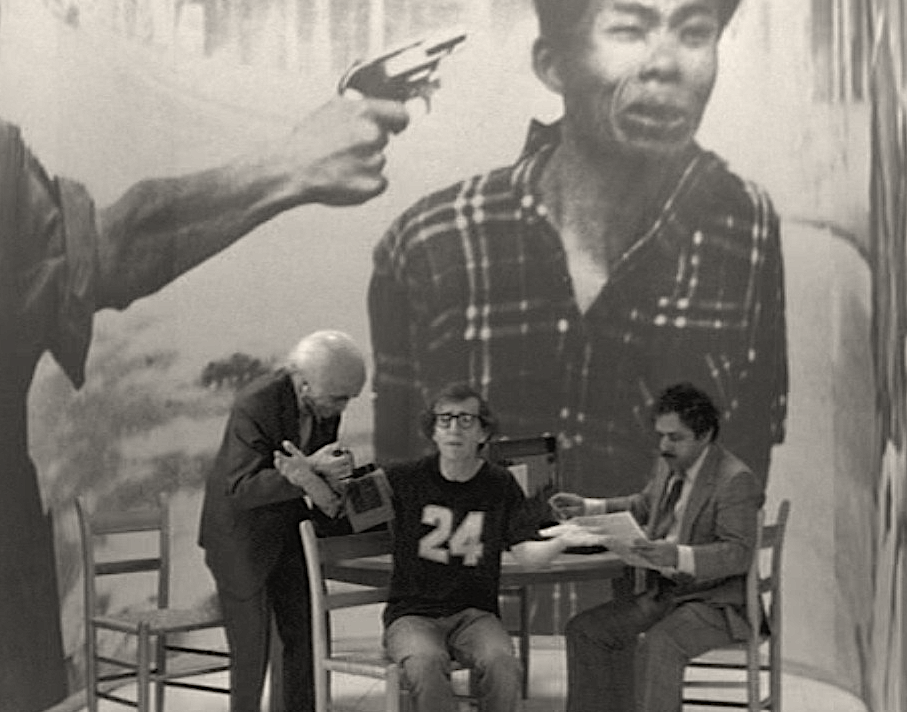

[IMAGE: Stardust Memories 1980]

New American Art

.

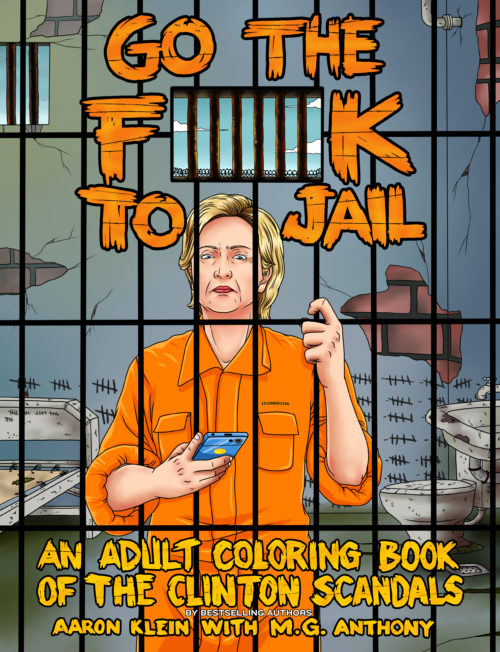

I saw this colouring-in book at the Philadelphia railway station. I couldn’t bring myself to buy a copy. My sense of irony didn’t stretch that far. It’s an interesting time to be in America.

Roman Candle

.

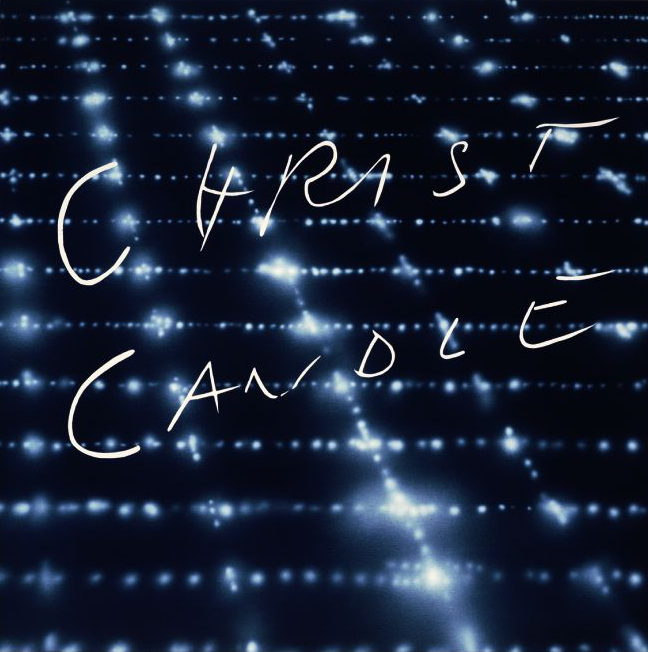

When you curate a show, you have to work with what you can lay your hands on, what someone else will lend, what you can afford to ship. When you’re based in New Zealand, that’s a major constraint. When we were doing the Sister Corita Kent show a few months ago, we wanted to present Ed Ruscha as a parallel figure—a Catholic (albeit lapsed) text-based pop artist. We borrowed the beautiful 1986 Ruscha painting, Love Chief, from Auckland Art Gallery. We hoped the words ‘love chief’—combined with the miraculous lights of the iconic LA street grid, viewed from on high—would carry enough religious connotation. But yesterday, visiting the Fisher Landau Center, in Queens, New York, I chanced upon the perfect example from the same series, Christ Candle (1987). It would have nailed our point like Christ to the Cross. QED.

Judging Book Covers

.

Our current Cindy Sherman exhibition surveys the American artist’s work from 2000 to now. In the 1980s, Sherman became famous for making theatrical photographs of herself. But then she went AWOL, photographing stand ins instead: mannequins and dolls, prostheses and masks. She retreated, as if allergic to her signature idea. In 2000, however, she returned to photographing herself, and she has been photographing herself as characters ever since. So, the Sherman idea got a second wind, but in a different moment, without the burden of the feminist critiques that seemed so crucial in the early days of the mission. Back then, Sherman’s work was cast as a critique of prescriptive mass-media images. But, when I look at the Head Shots (2000–2) now, they don’t suggest mass-media representations, but studies of the kinds of real women that aspire to live up to them and/or fail to. So, am I laughing at stereotypes or at actual women? Standing in the Head Shots room at City Gallery, I scan female faces, comparing, contrasting. I rank them by attractiveness; distinguish them by class and age. I separate the kempt from the feral, those who try too hard from those who should try harder. Sometimes I’m dismissive, sometimes sympathetic, sometimes both. Plus, I enjoy more specific associations: if one study recalls a nutty Carol Channing, another could be of a young Hillary Clinton. Every detail feels like a symptom. In the twenty-first century, Sherman’s work seems keyed less to feminism, more to social satire and caricature. She invites us to judge books by their covers—a guilty pleasure. Don’t miss it. (Cindy Sherman, City Gallery Wellington, until 19 March 2017.)