.

We join the rest of the art community in mourning the passing of our friend, Melbourne artist John Nixon. If anyone exemplified the imperative ‘stick to your knitting’, it was Nixon. For decades, he has pursued a practice focused on reworking a set of tropes derived from the historical avantgarde, bridging geometric abstraction and the readymade. Deceptively simple, his work could be at once idealistic and materialistic, hermetic and worldly, removed and engaged. It was spiritual yet designy, doctrinaire yet joyous. Artist Mike Parr once characterised it as ‘beleaguered transcendence’. In staying on message as the world turned, Nixon’s project continued to make new sense in new times, finding new champions and acolytes. His work—and his example of how to live and operate as an artist—inspired others, including our own Julian Dashper. It remains a compass point.

.

[IMAGE: John Nixon: EP+OW, City Gallery Wellington, 1997.]

•

Bouncy Castle

.

I’m involved in a new venture. Bouncy Castle is an imprint for publishing contemporary-art books in New Zealand. We will work with others—and go it alone—to publish important books on important art. We aspire to be the imprint of choice for publishing partners in this neck of the woods. Why do we call ourselves Bouncy Castle? Because it’s essential to defend a position but also to have fun. Our first book, Gavin Hipkins: The Homely II, is published in association with City Gallery Wellington. Available at better bookshops. [PS: Logo by our art director, Neil Pardington.]

•

Correction

.

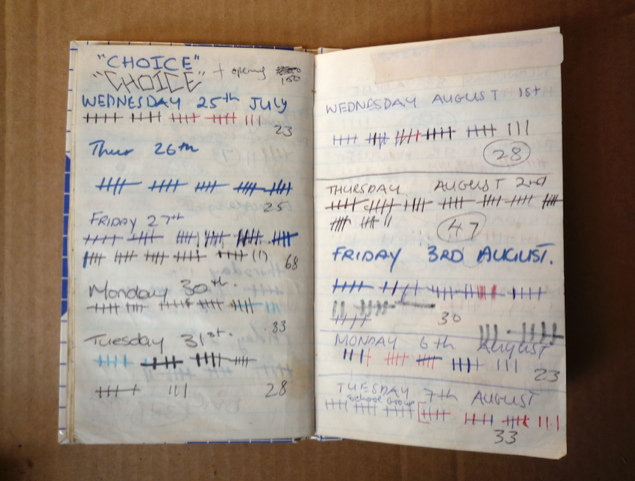

Actually, Jim Barr tells me, the Choice! attendance was more than 555. If one includes—as one should—the 150 (a round figure surely) at the opening, it should be more like 705. I got the 555 figure (which I have cited elsewhere) from Lara Strongman’s thesis The Awful Stuff, but Jim took photos of the attendance records themselves—so he wins! Facts will be the death of us.

•

Thirty Years Ago Today

.

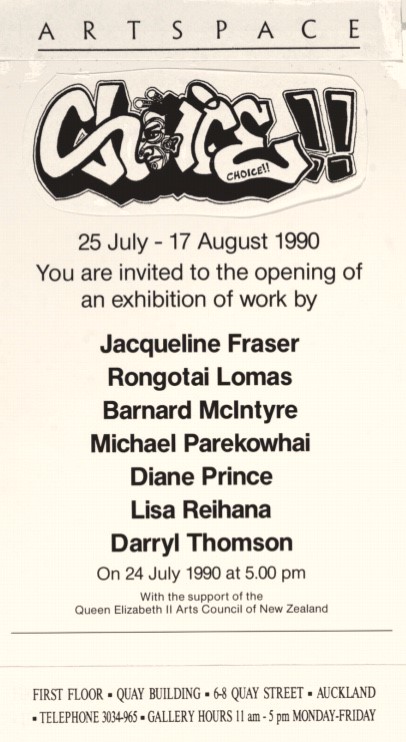

Time flies. Last week, curator George Hubbard emailed me to remind me that the thirtieth anniversary of his influential show Choice!, at Auckland’s Artspace, was almost upon us. How old we are.

Choice! challenged prevailing assumptions about what contemporary Māori art was or could be. By the end of the 1980s, contemporary Māori art—gallery-type art, anyway—was largely seen as centred on two groups. First, the Māori modernists, male artists who emerged in the 1960s (Hotere, Matchitt, Whiting, Wilson, Graham, Muru, Adsett, etcetera) and those operating in their wake. Second, women artists who emerged in the 1980s (Karaka, Rapira Davies, Kahukiwa, et al.). In 1990, Choice! ushered in a new generation of Māori artists who were, it implied, more than just ‘bearers of tradition and children of nature, re-presenters of the land and the past’.

The show was something of a mixed bag. It included outliers like Darryl Thomson (graffiti artist), Rongotai Lomas (filmmaker), and Barnard McIntyre (DIY neo-geo sculptor), but there were also Diane Prince (who could be considered part of the 1980s cohort of women artists) and Jacqueline Fraser (already prominent, but not as a Māori artist). It was the first gallery outing for Lisa Reihana’s iconic anti-racist video Wog Features, with its kids-TV-style stop-frame animations. And, crucially, it launched Michael Parekōwhai, still an Elam undergrad, with his cool, show-stealing, conceptual-art word sculptures. He would prove to be the show’s big discovery.

Throwing caution to the wind, Hubbard and his Pākehā collaborator Robin Craw penned a provocative polemic to accompany the show—‘Beyond Kia Ora: The Paraesthetics of Choice!’—warning that Māori art risked becoming ‘merely an ethnological echo of a hyper-historicised culture’. It was never clear exactly who were the targets of its shotgun arguments—presumptive Pākehā or the Māori-art establishment itself—but there certainly was a lot of smoke.

There were consequences. Like the Sex Pistols gig at Manchester’s Lesser Free Trade Hall in 1976, Choice! was important not because many people saw it (apparently only 555 visits were recorded), but for its profound and ongoing influence on those few who did. One of Parekōwhai’s word sculptures was acquired by bellwether collectors Jim Barr and Mary Barr, and all three would ultimately end up in public collections (at the Govett-Brewster, Auckland Art Gallery, and Te Papa). The show was reviewed by Giovanni Intra for Stamp and by Stephen Zepke for Antic, which also reprinted ‘Beyond Kia Ora’. I wrote on Parekōwhai for Art New Zealand and earmarked two of his sculptures for the Headlands show in Sydney (in which he would be the youngest artist), while Tina Barton suggested that Hubbard curate a Māori art show for Auckland Art Gallery (which ultimately became Korurangi: New Māori Art, 1995).

Choice! bridged contemporary Māori art and postmodernism. Around the time, I remember, some dismissed it as pandering to Pākehā taste—and there’s truth in that. But Choice! also saw, responded to, and harnessed an exciting new wave emerging in Māori art and creativity that is still playing out. In 2001, 2011, and 2017, Fraser, Parekōwhai, and Reihana would represent New Zealand at the Venice Biennale. Choice! is a textbook example of how a small show with a small budget and a small audience can be a gamechanger.

•

Exquisite Corpse

.

Necrophilia is not a routine topic in art. Consequently, some years ago, I was shocked to discover Gabriel von Max’s canvas The Anatomist on prominent display at Munich’s Neue Pinakothek—no apology, no trigger warning. It was painted in 1869, six years after Manet’s Olympia—when Freud was still in short pants. The anatomist (or coroner) is a bearded middle-aged man, formally attired, respectable. He’s a creature of darkness, barely there. In the privacy of his rooms, he meditates on a dead girl, drawing back the sheet to perv on her breast. She’s incandescent, hauntingly beautiful, creamy pale (but with lips and eyelids turning blue). Gift-wrapped in a body-hugging sheet, as if in bed rather than on the slab, she has been described as ‘like a bride’. We’re prompted to imagine the tragic circumstances that brought her here, so young. Drowning, by the looks. But was it foul play, suicide, or accident? Her corpse may be fresh, but an attentive moth reminds us that she will soon be food for worms; but not before the anatomist has satisfied his curiosities. Conflating the male gaze and the medical one, Von Max’s painting implictes us in its prurience—that breast is being uncovered for our benefit too. His painting generates its creepy frisson from the contrast between its risqué, taboo subject and conservative, academic painting style—an effect greatly enhanced when we gaze on its depicted intimate-private space from the bustling-public one of a museum.

•

Totem and Taboo

.

Last weekend, in Dane Mitchell’s show Letters and Documents at the Adam Art Gallery (on until 16 August 2020), I encountered my past in the form of a relic—Artspace’s old sandwich board. It had become an artwork, titled Artspace Totem.

I became Artspace Director at the end of 1996. I was only thirty-three, but I’d already worked as a curator in three museums and was seen by young artists as ‘the establishment’—fair game. It didn’t help that in Metro I was accused of corporatising Artspace—which will seem ludicrous to anyone who has seen how I dress. That said, one of my first acts had been to tart up the Artspace logo, reversing out Mary-Louise Browne’s original type from a black box to make it ‘smarter’. And, I did love the daily ritual of putting out my branded sandwich board on K Road, like a grocer.

In January 1999 or thereabouts, the sandwich board disappeared. I had no idea why. It turned out that two young artists, Dane Mitchell and Tim Checkley, had stolen it and taken it on a road trip. They photographed it at various stops—at Lake Taupo, the Desert Road, Te Papa, and somewhere between Westport and Arthurs Pass on the West Coast—before publicly presenting it in an old railways cottage in Otira as part of the exhibition Oblique: The Otira Project. After they’d had their fun, Mitchell phoned me, fessing up and proposing to return the sign to ‘neutral territory’—whatever that meant. I got impatient, stroppy, shrill. I didn’t know he was taping the conversation.

Later that year, Mitchell featured in Artspace’s emerging-artist show Only the Lonely. He presented a DJ desk, where visitors could mix a record of our phone call (with some added beats) with one of another prank call to Auckland Art Gallery Director Chris Saines. I insisted on using the Desert Road image for the exhibition invite, as I wanted to look like a good sport. But I did get tired of pretending not to care when the kids took potshots.

Actually, I took the mockery personally, even though it wasn’t clear to me what Mitchell and Checkley’s issue was or why this should be so funny. Perhaps the sign was my Achilles heel, and I was the last to realise. Maybe that’s why they redesignated it a ‘totem’, suggesting it had been mistakenly invested with mojo.

It was odd to see the sandwich board again. I’m surprised it still exists. Where has it been all my life? It may be a shadow of its former self—the vinyl logo has gone, leaving ghostly traces—but I’d know it anywhere. Reunited with it in Mitchell’s show in Tina Barton’s gallery, I was tempted to steal it back, wipe the smirk off both their faces, and take it on a road trip of my own. But I can’t run as fast as I used to.

.

[IMAGE: Tim Checkley and Dane Mitchell stealing the Artspace sign, 1999.]

•

Cosmopolitanism

.

There’s a memorable scene in John Ford’s 1956 western The Searchers. Ethan (John Wayne) is on a mission. He’s trying to rescue his niece (Natalie Wood) from the Comanche, who abducted her. While on their trail, he discovers the corpse of one of them and shoots out his eyes. The Reverend Clayton scolds him for being needlessly violent, but doesn’t know the half of it. The sadistic Ethan explains that he wanted to guarantee that the dead man could not pass into the afterlife, saying, ‘But what that Comanche believes, ain’t got no eyes, he can’t enter the spirit land. Has to wander forever between the winds. You get it, Reverend?’ It is a reminder that while understanding one another can enable greater sensitivity it can also enable greater insensitivity—or is it a more culturally sensitive insensitivity?

•

Time to Kill? Lockdown Puzzle!

Deaths of the Artists

Bas Jan Ader, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Aubrey Beardsley, Chris Burden, Keith Haring, Eva Hesse, Yves Klein, Édouard Manet, Ana Mendieta, Amedeo Modigliani, Pierre Molinier, Jackson Pollock, Egon Schiele, Georges Seurat, Robert Smithson, Vincent van Gogh, Andy Warhol, and Francesca Woodman. Match the names to their epitaphs.

.

22, suicide by defenestration. Said, ‘You cannot see me from where I look at myself.’

.

25, tuberculosis. Dandy. Said, ‘I have one aim, the grotesque. If I am not grotesque I am nothing.’

.

27, heroin overdose. His tag was a crown.

.

28, Spanish flu. Said, ‘He who denies sex is a filthy person who smears in the lowest way his own parents who have begotten him.’

.

31, meningitis. Said, ‘Some say they see poetry in my paintings; I see only science.’

.

32, AIDS. ‘Crack is wack.’

.

33, presumed lost at sea. Emo.

.

34, from his third heart attack in two months. Said, ‘Blue has no dimensions.’

.

34, brain tumours. Said, ‘Don’t ask what the work is. Rather, see what the work does.’

.

35, plane crash. Said, ‘Abstraction is everybody’s zero but nobody’s nought.’

.

35, tubercular meningitis. His widow—eight months pregnant with the couple’s second child—committed suicide by defenestration the following day.

.

36, fell from her thirty-fourth-floor apartment. Her artist husband of eight months was acquitted—twice. In one of her performances, she had held a freshly decapitated chicken by its feet as its blood spattered her naked body.

.

37, probable suicide, by gunshot. Said, ‘The sight of the stars makes me dream.’

.

44, car crash. Said, ‘I am nature.’

.

51, eleven days after his gangrenous left foot was amputated due to complications with syphilis and rheumatism. Painted a dead toreador.

.

58, arrhythmia, following a routine gall-bladder operation. Said, ‘Death is the most convenient time to tax rich people.’

.

69, melanoma, after near misses with gun and electrocution, and being crucified on a car. Said, ‘Nail me to my car and I’ll tell you who you are.’

.

75, suicide by hanging. The note said, ‘I’m taking my life. The key is with the concierge.’

.

Answers here.

.

[IMAGE: Vincent Van Gogh Skull of a Skeleton with Burning Cigarette c.1885–6]

•

Bubble

.

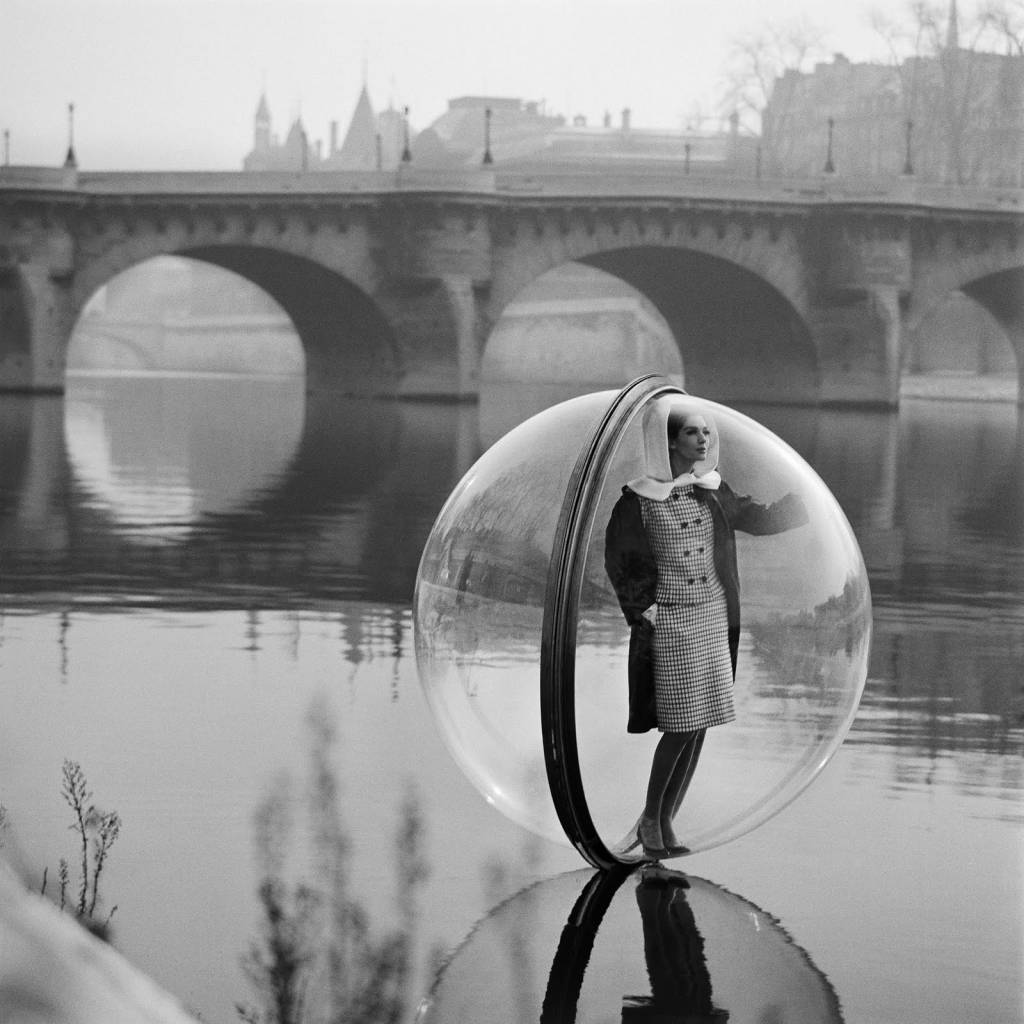

I’ve always loved Melvin Sokolsky’s fashion-photo series The Bubble, published in Harper’s Bazaar in 1963. It seems especially resonant right now, with us all in our bubbles. Model Simone d’Aillencourt floats through Paris, encased in a Plexiglass ball. She appears to be at once inside and outside the scene, an object of the gaze yet also the embodiment of the gaze within the image—like us, a tourist.

•

Gilded Cages

.

I love excavating bookshops, unearthing unexpected gems. My latest acquisition is Ads by the French artist Pierre Leguillon (Brussels: Triangle Books, 2019). It reproduces seventy magazine ads featuring artists, from the 1940s to now. The tear sheets are ordered alphabetically by the artists’ surnames, starting with Marina Abramovic, ending with Aaron Young. They are presented without further curation or comment. Draw your own conclusions.

Most of the ads feature instantly recognisable, world-famous, ‘name’ artists (Vanessa Beecroft, Louise Bourgeois, Maurizio Cattelan, Tracey Emin, Robert Rauschenberg, Julian Schnabel, Andy Warhol), with a few lesser figures thrown in. No one is there to flog art. Most ads are for clothes brands. Some are for booze (Salvador Dalí fronts for Scotch), for cameras (Norman Rockwell!), for jewellery and watches (Anh Duong and Helen Frankenthaler), and for travel (Mr and Mrs Max Ernst on a cruise). There’s only one downmarket product placement, painter Hebru Brantley in his studio eating McDonald’s. (Caption: ‘Starving artist? I don’t think so.’)

Some marriages seem counterintuitive: gritty war photographer Don McCullin endorses luxury menswear while Jean Cocteau sells televisions. Some artists strain to look sincere, ‘keeping it real’, like those unsmiling Starn Twins or the equally unsmiling Ed Ruscha, with his cultivated Richard Avedon ‘American West’ look—all three posing for Gap. The artist who survives intact is the great pretender, Cindy Sherman, collaborating with photographer Jurgen Teller, for Marc Jacobs. She camps it up, brandishing a guitar as if she were a fake rock star rather than a real art star. Of course, the ads also seek to flatter those of us who know who Cerith Wyn Evans is.

Ads recalls Picturing ‘Greatness’, the show Barbara Kruger curated for the Museum of Modern Art in 1988. There were thirty-nine portraits of great artists (mostly white males) from the photography collection, including shots of Rodin, Picasso, Duchamp, Rodchenko, Pollock, and Henry Moore. They were accompanied by a short polemic. In it, Kruger wrote: ‘Though many of these images exude a kind of well-tailored gentility, others feature the artist as a star-crossed Houdini with a beret on, a kooky middleman between God and the public.’ Picturing ‘Greatness’ surveyed the ways artists presented themselves to the camera, colluding with friendly photographers to perfect an idea of how artists ‘look’. However, Kruger explained, these images can also ‘show us how vocation is ambushed by cliché and snapped into stereotype by the camera’.

In Ads, Leguillon seems to savour the way artists’ status is at once affirmed and eroded. Replaying Kruger’s idea with a twist, he shows how third parties muscle in on the magic to cash in on the artists’ cachet, but also how artists let them. As many of the artists included have more money than God, we know they didn’t need to make these ads—but chose to, aspired to. I wonder, in the distant future, if all that is left of art is Leguillon’s book, how would anthropologists understand ‘the artist’?

•