.

Will there be a catalogue?

•

The Downside of Creativity

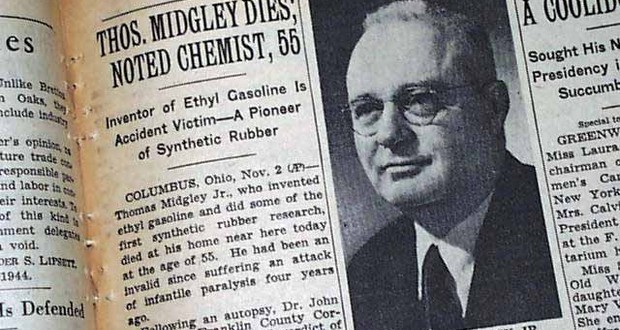

The art world is alight with feel-good rhetoric about ‘creativity’. We celebrate it as intrinsically beneficial. But creativity looks less benign outside the white cube in the real world, where its consequences can be dire. Take the American mechanical and chemical engineer Thomas J. Midgely. Granted more than a hundred patents, he was clearly rather creative. He will be particularly remembered for two creations: leaded petrol and chlorofluorocarbons. Both were later banned due to their disastrous impact on people and the planet. Midgely has been described as a ‘one-man environmental disaster’ with ‘more impact on the atmosphere than any other single organism in Earth’s history’. Interestingly, he would be a victim of his own creativity. In 1940, aged 51, he contracted polio and devised an elaborate system of ropes and pulleys to lift himself out of bed. Four years later, he became entangled in the device and died of strangulation. Thought experiment: If you had a TARDIS, would you go back and eliminate Midgely before he created his bad things and thus save the world? If so, would that make you a creativity killer?

•

Pharmakon

.

There’s a lot of clamour around ‘art history’ right now. On the one hand, universities are cutting art-history departments—it’s part of the neoliberal purge of the humanities, we’re told. On the other hand, art history is under attack from the left—as a bastion of crusty white privilege. Of course, when people talk about ‘art history’, they are often talking about very different things. For many people, ‘art history’ conjures up notions of the canon, and the image of Lord Kenneth Clark in his tweed jacket fronting the 1969 BBC TV show Civilisation, laying out the Western high-art tradition. (I was six.) However, we tend to forget that, just three years later, in 1972, BBC2 screened John Berger’s Ways of Seeing—a Marxist-feminist critique of Civilisation. (I was nine.) When I started studying art history at the University of Auckland in the early 1980s (still a teenager), it was still all about the Western tradition (white males), and, to proceed to post-grad, you had to study a European language (French, German, Italian, or Spanish). However, all that was rapidly coming unstuck. A Women in Art paper was introduced (which I did), followed (after I left) by papers on New Zealand art, contemporary art, and Maori and Pacific art. Today’s art-history courses bear little resemblance to the one I did. Similarly, in my later life in art museums, art history would be always under scrutiny while being furiously transformed. For as long as I have been involved in it, art history has been in a state of perpetual and profound revision, philosophical and political expansion. Indeed, for me, art history is that business of rewriting. Art history may be, at once, the field and the game that’s played upon it; poison and cure, scapegoat and straw man. Pharmakon.

.

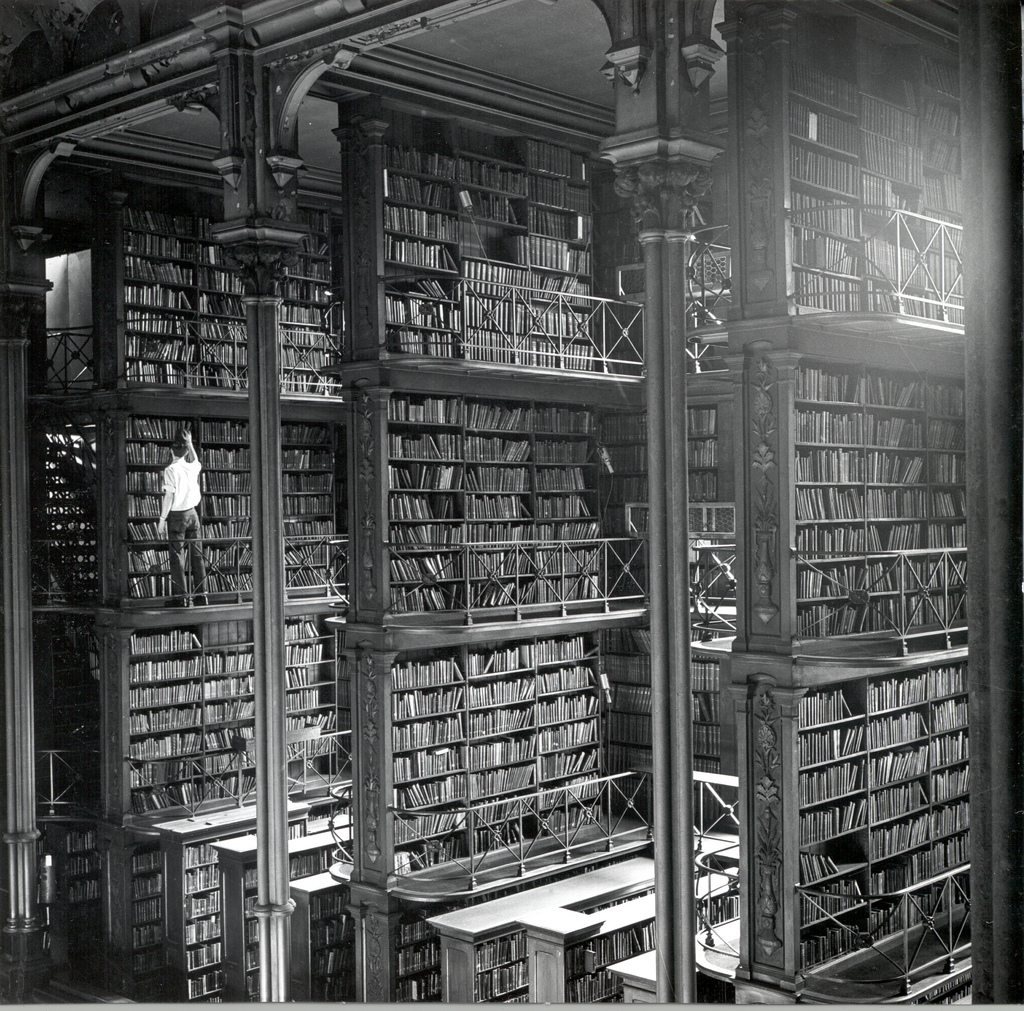

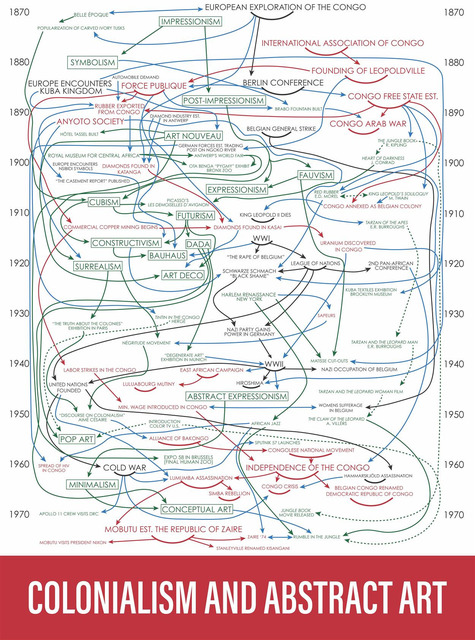

[IMAGE: Hank Willis Thomas Colonialism and Abstract Art 2019]

•

Today Is the First Day of the Rest of My Life

.

I’m no longer at City Gallery Wellington, however I hope you get to see my four current shows, which opened there yesterday: Brett Graham: Tai Moana Tai Tangata, Judy Millar: Action Movie, Tia Ranginui: Gonville Gothic, and Pierre Huyghe: Human Mask (until 31 October). People have been asking me about my plans. For now, I’m focusing on writing and publishing. I’ve joined Art News New Zealand as Editor and I’ll be revving up my work on Bouncy Castle. Our second title—Giovanni Intra: Clinic of Phantasms—is almost off to the printers. It’s being co-published with Semiotext(e). Two more books are in the pipeline. I’m also looking for opportunities to curate and consult; advise and assist; write and edit. I can be contacted on my new email BouncyCastleLeonard@gmail.com. Don’t be shy.

.

[IMAGE: Salad days. I enjoy a light lunch at Villa Blanca, Beverly Hills, Los Angeles, alongside its owner Lisa Vanderpump, 2016. Photo: Michael Zavros.]

•

Happy or Sad?

.

It’s not one of Rita Angus’s great paintings, but I’ve always had a soft spot for Churches, Hawke’s Bay. ‘Church’ suggests congregation, a united community. But, in the painting, multiple churches are grafted together or emerge from one another haphazardly, suggesting competing views, schisms, a fractured community. One of the churches is a wharenui. As if to echo this doctrinal discord, there’s no ruling perspective at work in the painting. The artist looks at once to medieval painting (before Albertian perspective) and to cubism (its undoing). Faceless people are peppered about, looking somewhat awkward and isolated, like they don’t know where to turn in the visual and ideological clamour. Perhaps those eye-candy colours are deceptive. Is this a happy painting or a sad one—an image of community or alienation, utopia or dystopia? I don’t know.

.

[IMAGE: Rita Angus Churches, Hawke’s Bay 1962–3]

•

More than Human

.

Human thinking has generally been human-centric, drawing a line between consciousness and the world, humans and everything else. That’s why animals are so perplexing for us, because we don’t know which side of the line to put them on, whether to relate to them as other sentient beings like us or as objects for us. Art has emphasised this human-centric approach, locating artists (and, by analogy, their viewers) at the sovereign centre of the world, with things arrayed for their (and our) benefit, addressed to them (and us). We have learnt to take this approach for granted. So, for me, it was profoundly disorienting to see Pierre Huyghe’s project Untilled in Documenta 13 in Kassel, Germany, back in 2012. A game changing moment.

Untilled occupied an out-of-the-way location—a dowdy area where one was not expected to go—at the edge of the otherwise scenic Karlsaue Park. I entered via a beaten track, passing piles of compost and algae-covered puddles. The site was overgrown with plants, including psychotropic, medical, and aphrodisiac ones (cannabis, deadly nightshade, and angel’s trumpets). Concrete paving slabs were stacked up matter of factly, as if waiting to be deployed elsewhere. The apparent centrepiece was a conventional sculpture of a female nude on a plinth—a replica of a 1930s work by Max Weber. But, by the time I arrived, the head had been replaced—or colonised—by a hive of bees. A greyhound called Human, with one leg painted pink, wandered around freely. Many obscure reference points—including nods to Huysmans’s novel À Rebours and Raymond Roussel’s novel Locus Solus—were apparent only by reference to a drawing in the exhibition guidebook.

Untilled didn’t look like any artwork I had ever seen—it didn’t look like art full stop. Stuff was rotting; stuff was growing; stuff was interacting; stuff was waiting to be turned into something else somewhere else. Potential was everywhere. There was no clear frame to show where the work started and stopped. It was hard to know what was in or out, what was significant and what was incidental, what had been found and what had been added by the artist. Not only was the work not addressed to me, it incorporated flora and fauna with lives and purposes of their own, engaging with this scenario alongside me on their own terms. The work seemed free to evolve or devolve, beyond any artistic intention. There was no clear drama, no spectacle, yet the effect was uncanny, even menacing. I was reminded of The Zone in Tarkovsky’s film Stalker.

Only later did I come to appreciate the full significance of Untilled, as breaking from a human-centred perspective. It heralded a new approach to art making, with more art operating in this vein appearing in its wake. Today, knowing we have brought the planet to the brink ecologically, there’s an appetite for less-chauvinistic attitudes—orientations that deprioritise human perceptions and demands. This imperative informs new philosophical approaches, such as Graham Harman’s object-oriented ontology. In different ways, Zac Langdon-Pole and Simon Ingram—both currently showing at City Gallery—participate in this Zeitgeist. They adopt decentered approaches: Langdon-Pole collaging things to collide their disparate, often inhuman frames of reference (an octopus shell and a meteorite); Ingram by understanding the artist as just one node in the assemblage that produces the work. (Zac Langdon-Pole: Containing Multitudes and Simon Ingram: The Algorithmic Impulse, until 7 March 2021.)

.

[IMAGE: Pierre Huyghe Untilled 2012]

•

Art-Goes-to-the-Movies Quiz

.

Who played these real artists in the movies?

Rembrandt in Rembrandt (1936)

Paul Gauguin in Lust for Life (1956)

Vincent van Gogh in Lust for Life (1956)

Michelangelo in The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965)

Andrej Rublev in Andrej Rublev (1966)

Camille Claudel in Camille Claudel (1988)

Dora Carrington in Carrington (1995)

Jean-Michel Basquiat in Basquiat (1996)

Andy Warhol in Basquiat (1996)

Pablo Picasso in Surviving Picasso (1996)

Francis Bacon in Love Is the Devil (1998)

Willem de Kooning in Pollock (2000)

Lee Krasner in Pollock (2000)

Jackson Pollock in Pollock (2000)

Frida Kahlo in Frida (2002)

Johannes Vermeer in The Girl in the Pearl Earring (2003)

Amedeo Modigliani in Modigliani (2004)

Diane Arbus in Fur (2006)

Margaret Keane in Big Eyes (2014)

J.M.W. Turner in Mr Turner (2014)

Alberto Giacometti in Final Portrait (2017)

Vincent Van Gogh in At Eternity’s Gate (2018)

J.S. Lowry in Mrs Lowry and Son (2019)

.

Answers here.

.

[IMAGE: dir. Tim Burton Big Eyes 2014]

•

Fools to Judge My Work

.

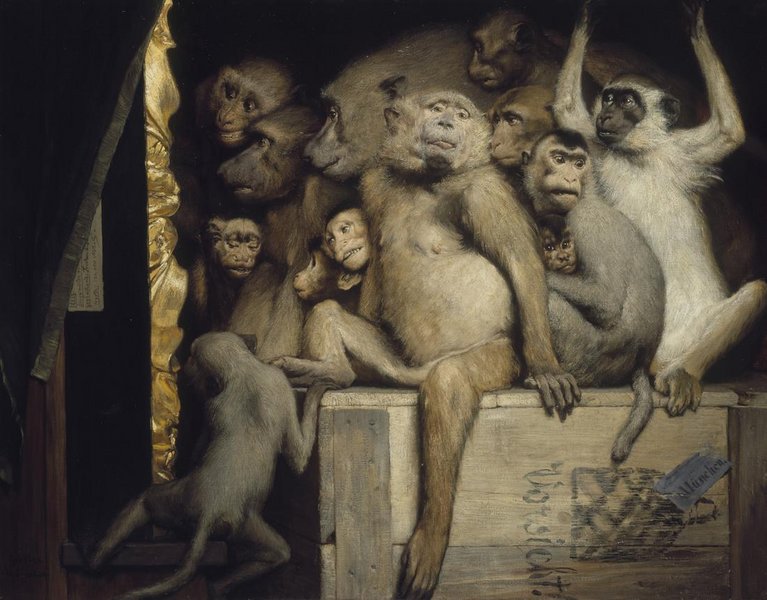

Gabriel von Max was an oddball nineteenth-century Czech-born German painter. He was rated for his religious paintings, but he spent much of his time painting monkeys—considered an inferior pursuit at the time. He even earned the title ‘Affenmaler’—monkey painter. In this 1889 painting, he presents his furry friends as a cohort of art critics. They strike poses: grandiose, quizzical, and imbecilic. They are us, yet not us. Perhaps it was a trap for anyone who dared to judge his own work, with Von Max holding up a mirror to his critics. As a curator—straddling the realms of art production and reception—I don’t know whether to take it personally. Which side of the fence am I on? Am I among the critics (judging the art) or at their mercy (making exhibitions alongside the artists)? No offence to monkeys.

.

[IMAGE: Gabriel von Max Monkeys as Judges of Art 1889]

•

Poetic Justice

.

If I won Lotto, I would endow a writing prize for premature obituaries. I’d invite writers to pen obituaries for living persons of note, assuming they will die five years from now. The writers will have to be true to what has already occurred, but can invent the future as fancifully as they wish, perhaps granting their subjects the last chapters and deaths they deserve—flattering or otherwise. Get creative. We publish the best.

[IMAGE: Henry Wallis The Death of Chatterton 1856]

•

Post Hoc

.

As soon as we went into lockdown (the first time), I began missing the art life. I wondered when galleries would reopen. I wondered when borders would reopen and artists and curators from elsewhere would be visiting, bringing energy and information. I wondered when I might be back on planes, visiting art capitals, grazing biennales, doing business. Now I’m thinking—if and when borders reopen—will there even be biennales, art capitals, and art as we know it? Will the game have changed, fundamentally?

Isolation has always been a problem for New Zealand artists. Last century, they enjoyed local careers—international opportunities were exceptional, the icing. But, in the last twenty years, our art system has become predicated on working internationally, changing the scale and scope of our art—the dynamics of production and reception, the rewards. Consider Mata Aho, whose work was picked up early for Documenta and is now shaped by international exhibitions and the opportunities they bring. Internationalism has enabled our artists to be part of more complex and more specialised conversations.

Since 2001, New Zealand has been sending artists to Venice to help springboard them (and us) into the international discussion, the big league. In 2019, we sent Dane Mitchell. His show Post Hoc—tellingly concerned with things that have become extinct—was immediately followed by the pandemic. Like many of our successful artists, Mitchell faces losing momentum as opportunities to work internationally dry up, making it hard to capitalise on Venice. The timing couldn’t be worse for him. Indeed, the pandemic’s implications may hit hardest our most ambitious artists—who have already outgrown what New Zealand can offer, resource-wise, audience-wise.

What can be done? I was once advised that there are three responses to crises: resist, succumb, and exploit. Should we stay the course with our internationalism (double down)? Should we adjust to having a more intimate, enclosed, domestic scene (as in the 1980s, say)? Or are there also opportunities hidden in our current fraught moment? What role will agencies and individuals play in fronting this discussion and in the work that follows?

•