Reading Room, no. 2 (2008).

_

.

Giovanni Intra died on 17 December 2002 in New York. He was only thirty-four. In his short life, he wore a number of hats in the art world, in New Zealand and later in the US. In the early and mid-1990s, he was a fixture on the New Zealand art scene, making a major contribution as an artist, writer, and gallerist. Last year, Auckland Art Gallery’s E.H. McCormick Research Library received a substantial deposit of archival material from his New Zealand years from his mother Barbara Intra. This archive rounds out our understanding of the artist and will provide fertile soil for researchers.

Intra studied at University of Auckland’s Elam School of Fine Arts, finishing his BFA in 1990 and his MFA in 1993. He was a precocious student. His work first developed out of an unlikely marriage of punk and religion. He had been in a punk band called the Negative Creeps. And in 1989 he visited India, where wayside shrines fascinated him. On returning, he started producing votive objects out of cheap materials: fragments of paper, tin foil, ribbon, wax, lace, sequins, found images. He showed these talismans in ritual accumulations, sometimes arranged on the floor and sometimes pinned to the wall in clusters in the manner of New Zealand artist Richard Killeen’s cut-outs. Part order, part chaos, his shrines celebrated religion’s dark side: destruction, annihilation and fetishism. One was dedicated to American punk novelist Kathy Acker.

By the end of 1990, Intra had jettisoned the Indian references and was creating reliquaries of punk attire and gestures. His evacuated ‘studded suit’ (Untitled, 1990) recalled Joseph Beuys’s felt one, but could not have been more different, merging fetish fashion and religious fetish. He displayed Doc Martens, a studded wristlet and a razor in a glass case, suggesting a time capsule, a memorial to punk’s passing (Lifestyle Morte, 1991). He photographed a hand giving the ‘fingers’, spit on glass, and open mouths with tongues supporting pins and pills.

A voracious reader, Intra gobbled up Greil Marcus’s Lipstick Traces (a ‘Secret History of the Twentieth Century’, which traced punk’s descent through situationism back to surrealism) and Dick Hebdige’s Subculture: The Meaning of Style (a Marxist reading of subcultural aesthetics). But he ended up turning to Georges Bataille, the French dissident surrealist and librarian-pornographer. As he explained in his 1993 MFA dissertation ‘Subculture: Bataille, Big Toe, Dead Doll’: ‘In Bataille the sub is not so much a “culture” but an area of philosophical aggression: the field of “excremental philosophy”, heterogeneity, and transgression. This is what I term subculture, thus relating Bataille’s ideas to contemporary manifestations, in particular punk … Bataille’s low can be found in the abject manifestations of culture; pornography, unlimited proletarian revolution, automutilation, madness, excess, and extreme ecstasy (eroticism, religion, spillage): what opens onto the unthinkable, in short, the impossible. Subculture, then, is a kind of offal, a waste product of the homogeneous system, a commodity produced but unaccounted for, an unplugged abyss in culture.’1

Intra paid homage to surrealism. His Blood Mobile (1992), made of suspended pieces of blood-red glass, nodded to Hans Bellmer, while his over-engineered tableau Corps Humain (1992) quoted Rene Magritte. Through surrealism that Intra became obsessed with medicine and hallucination. His article ‘Discourse on the Paucity of Clinical Reality traced surrealism’s conception back to a World War I field hospital and the young neuropsychiatric intern Andre Breton’s chance encounter with a deluded soldier certain the war was an elaborate fiction.2 Intra was also interested in a Bataille collaborator, the photographer Jacques-André Boiffard, whose photographs of big toes and gaping mouths were informed by medical photography.

Intra used medical materials and processes throughout his work. With Vicki Kerr, he remodelled Teststrip gallery, curving walls, ceiling and floor together, painting it white and dousing it with disinfectant. Conflating gallery and operating theatre, they called it Waiting Room (1993). He sterilised a still life of vegetables, fruit and surgical disposables using Cobalt-60 irradiation in Corpus Delicti (1993), and asked his audience to perv at a video of a tomographic scan of a human pelvis through a security peep-hole in Scopophilia: Jacques-André Boiffard (1993). He sequestered a rat loaned from the University of Auckland’s medical school behind an epidermal wall of pink fibreglass batts for an Artspace art-and-science theme show (1994). He apparently also made paintings with spermicide.

Intra wanted to expose a perversity underpinning the assertively rational medical business, transforming it ‘in bouts of necrotic flanerie’, hoping to make ‘medical use-value glisten with the perverse thrill of ulterior motive’.3 He wrote: ‘We begin where the epistemological figures “disease”, “trauma”, and “malady” lose their clinical specificity; where medical textbooks are nothing but recipes for perversion and atlases of anatomy are all the better as collage material.’4

Medicine (today’s truth) and religion (yesterday’s truth) came together in Unrequited Passion Cycle (1993), a collaboration with New Zealand writer Stuart McKenzie. Playing off the thought that medicine had replaced the Church as the source of hope and miracles and truth, Intra made fourteen photographs illustrating McKenzie’s irreverent alternative slogans for the Stations of the Cross (including ‘Male Pin Up’ and ‘Cross Dresser’). Intra represented the slogans with medical supplies (a catheter, a drip, spermicide, band aids) photographed floating above a transcendental blue background, suggesting an antiseptic sublime. Intra explained: ‘I responded to the Passion Cycle like a mad doctor, putting a contemporary medical perspective on it—if Christ turned up at Auckland Hospital on a Saturday night, what would happen to him?’5

Intra’s assault on medical science’s presumption to objective truth was ultimately literalised in acts of vandalism. He started smashing up optical technologies—cameras mostly, but also a microscope and a computer monitor—coyly describing these works as ‘disarticulated readymades’. For The Way Doctors See (1995) he spread the remains of thirty trashed cameras across the floor in a vandalistic orgy. The installation Hospitals (1995) at Manawatu Art Gallery in Palmerston North recalled a ransacked clinic. He also created x-rays of cameras, intact and smashed, perversely folding technology’s gaze back on its own demise, as if he could see through it. To me the x-rays had a psychedelic quality, recalling the ultimate scene of Michelangelo Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point, where a modernist house and its consumer contents are blown up in glorious slow motion in a way that seems to cross-reference a scientific experiment and a drug trip.

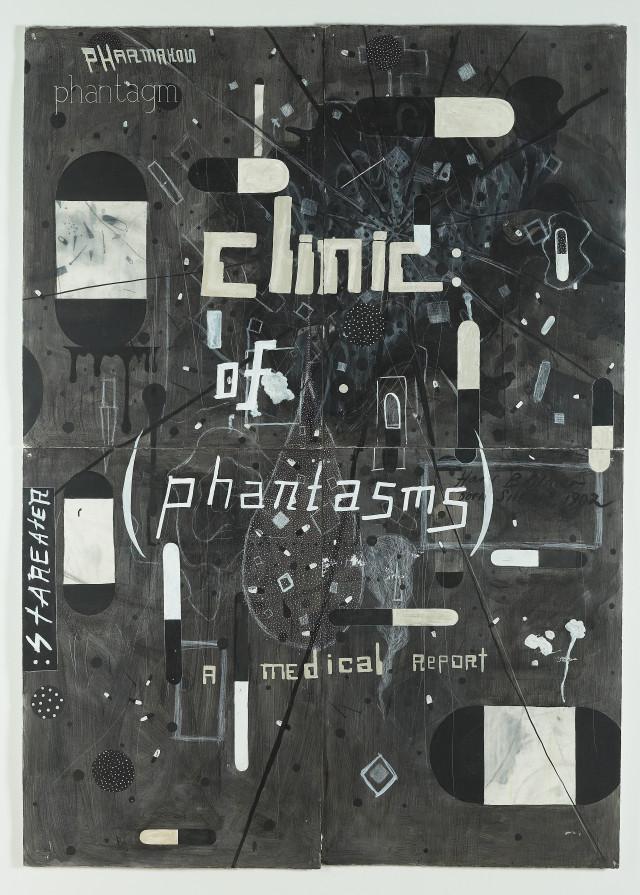

Drawing was always important for Intra. He drew incessantly to gather and trial ideas. His adolescent ‘pencil case’ aesthetic made a feature of lettering, for instance juxtaposing refined copperplate script with corny ghoulish dripping-blood lettering. In 1992, Intra’s drawing found epic expression in a cycle of massive works on paper, originally hung edge to edge as a mural. These handmade billboards mind-mapped his diverse concerns: punk bands (Jonestown Olympics), dadaists and surrealists (Picabia, Magritte, and Bellmer), philosophers (Derrida), medical and recreational drug use. One of the loveliest, Clinic of Phantasms, offered a constellation of pills in a trippy Clairmontesque conflation of internal and external realities. It is now owned by Te Papa.

The last works Intra showed in New Zealand, at Auckland’s Anna Bibby Gallery and Wellington’s Hamish McKay Gallery in 1996, also developed out of his drawing. With their white inscriptions on black grounds, they recalled Colin McCahon’s late text paintings. In place of scripture, Intra opted for, what William McAloon called ‘a conspiracy of fantasies’,6 being peppered with Artaudisms, cryptic druggy neologisms, paranoid tags, and in-jokes: ‘Colombianizacion’, ‘Panadology’, and ‘Hollyweird’. Intra gathered these small inane art-brut nocturnes in elaborate ensembles, arranged on base lines suggesting city skylines, bar graphs, and books on shelves, as if to mock the very semblance of order or closure.

Intra was also one of the founders and key players in the influential artist-run gallery Teststrip, a critic and curator. These activities played into his wider inquiry. He co-opted Stamp magazine as a platform for his writing early on, later graduating to the mainstream art press. Epitomising the idea of the artist-writer, his writing and curating picked out things in other artists’ works that interested him. ‘Mental Health in the Metropolis’ repositioned John Hurrell as a situationist; ‘A Case History: Tainted Love’, a catalogue essay on Fiona Pardington, focused on medical photography and perversity; his show Everyday Pathomimesis linked artists around the theme ‘studies in the disarticulation of disease’.7

Intra was always destined for greater things. He was befriended by Sylvere Lotringer, the publisher of Semiotext(e) and prominent LA academic, while he was visiting New Zealand with his partner, expatriate New Zealander Chris Kraus. In 1996, Intra left for LA on a Fulbright Scholarship to study at Art Center College of Design, in Pasedena, where his teachers would include Lotringer, Mike Kelley, and Stephen Prina. In LA, he effectively stopped working as an artist and focused on writing. He rapidly became a prominent art critic, contributing to major journals like Artforum, Flash Art, and Tema Celeste. However, he was most visible in the Australian magazine Art and Text, for which he began writing while in New Zealand. It had also relocated to LA around the same time. In 1999, with his friend Steve Hanson, who also worked at the Art Center library, Intra started a low-key artist-run space, China Art Objects. It quickly became an influential dealer gallery through featuring collaborations between emerging and established LA artists and giving first shows to artists who subsequently became important. Intra was just getting started, but he was already a success. When he died, Roberta Smith wrote an obituary in the New York Times and Frieze did a two-page story.

With Intra’s death, New Zealand lost not only a close friend but also a key link to the international art world. He had become a conduit for information and opportunities, facilitating connections both ways for artists and curators, into and out of New Zealand. Like many at the time, I wondered what might be done to pay tribute to Intra. At that stage, his work as an artist was effectively mothballed. He had left it in storage and had not been attending to his profile as an artist. Out of circulation, the work was no longer part of the current discussion, but had not entered into history either. Should it now be celebrated as a key aspect of New Zealand art of its time or seen as a sidebar story at best? Actually, you could go either way. It was certainly easy to forget how crucial Intra had been to his moment, how he had brokered new ideas into the New Zealand discussion. His work also shared strategies, images and interests with important contemporaries, among them Luise Fong, Gavin Hipkins, Denise Kum, Daniel Malone, Fiona Pardington, Ava Seymour, and Et Al. He even did a collaborative work with Michael Parekowhai, who went through Elam sculpture with him. He was part of a scene.

When Intra died I was about to start a new job, as curator of contemporary art at Auckland Art Gallery. My first task was to curate an exhibition from the Chartwell Collection, which included one of Intra’s ‘conspiracy’ paintings. I decided to focus on eight canonical figures in New Zealand art, all well represented in the Chartwell and the Gallery collections (Et Al., Peter Peryer, Bill Hammond, Julian Dashper, Michael Stevenson, Jacqueline Fraser, John Reynolds, and Michael Parekowhai), plus Intra. At that stage, the Gallery owned nothing of Intra’s, but quickly acquired the studded suit, jointly with Chartwell. While the other eight artists were represented with works from the two collections, I built a mini-retrospective of Intra’s works drawing extensively on loans and reconstructions. It seemed a provocative idea, to locate Intra—an artist of ambiguous standing—in the mix of these more recognised figures. To brand the show I used Monty Adams’ image of a female model wearing the studded suit from a fashion spread in Planet.8 I called my show Nine Lives, in reference to the nine artists surveyed but also to Intra’s demise, and the fragility of artists’ lives and reputations. Conveniently, a black cat appeared in Adams’s image.

Assembling the Intra part was rushed, but it seemed important to do something quickly. I had trouble finding works. A key early piece, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery’s Nature Morte (1990), was too fragile to travel, so I couldn’t represent the beginning of the story, those ritualistic Indian works. Two works I had completely replicated: the etched mirror piece An Excellent Fetish (1991) from photos and The Way Doctors See from a description and with the help of Gavin Hipkins. For Scopophilia: Jacques-André Boiffard, I installed Intra’s video of a pelvis behind a security peep-hole in a wall painted medical green. I matched the paint colour perfectly to a slide documenting the original installation, although someone told me it was way off. I struggled to find out which way up Intra’s x-rays went.

Of course, when you do a show of an artist who has just died there are always people close to them with a vested interest in telling you that you got it wrong. Interestingly, at the Nine Lives opening, Intra’s friends, lead by Ava Seymour, stomped through The Way Doctors See, further dispersing its camera scraps through the space in an impromptu happening. Someone said this was necessary because Hipkins and I had installed it too prissily—although Intra could be piss elegant with his installations. Someone else said the work should be on a carpet, confusing the work we re-presented with another, The Enchanted Garden of Childhood (1995). Intra’s circle’s vandalistic participation seemed to be part of a grieving process. Doing Nine Lives brought home to me what it means to curate a contemporary artist’s work after they die, where you can’t ask them what they did or why, where you are limited by shaky memories and the limited documentation to hand.9 So, I was thrilled when I heard that Barbara Intra had deposited her son’s papers with the Library. They would have been so helpful to me when I was making Nine Lives. Going through the boxes, Intra’s project came to life for me again.

Intra placed huge importance on his often scruffy, scratchy drawings, binding photocopies of them into volumes, thesis-style. There were lots of drawings, flicking out ideas for Blood Mobile and other installations of ‘disinfected minimalism’. I particularly loved one unrealised idea, for a photograph of a reconstruction of Caspar David Friedrich’s famous sea of ice in frozen savlon. There was a swag of photographs: shots from travels through India, snapshots of parties and friends, images of works and shows, plus primary material for photographic works, including the 4×5 negatives Ann Shelton shot for Unrequited Passion Cycle. There was a clunky early art school video work, and a VHS tape of Intra playing with the Negative Creeps. The archive shows how Intra’s writing developed in conversation with his practice as an artist. It contains what appears to be an awkward university assignment on Anish Kapoor (which may relate to Intra’s Indian-inspired work) and reviews done for Alberto Garcia-Alvarez’s Elam art-criticism class. There are miscellaneous published reviews and articles including some of his early pieces for Stamp magazine; a bound copy of his MFA dissertation (plus drafts, notes and reference materials); and correspondence with Barbara Blake over ‘Germ-Free Adolescence’, the interview they did for Art New Zealand. The correspondence is also amusing. Call it Schadenfreude, but I enjoyed reading Intra’s mock-pompous responses to his critics, especially one letter sledging Justin Paton after a damning review. Paton’s review must have been more than compensated for by something else I found: a fax from Rosalind Krauss expressing interest in considering an Intra essay for October. The archive also provides ample evidence of Intra’s sheer determination, particularly during his push to get to LA, with him constantly writing to people to solicit financial support. He was someone who could make things happen.

Poring over all this stuff afforded me a new understanding of Intra’s intellectual and artistic evolution. I could see how his inquiry unfolded through the prism of his very distinct concerns and sensibility. I could see how he fed his project philosophically and practically on anything and everything to hand. It is fitting that an artist who owed so much to archives should now become one.

.

[IMAGE: Giovanni Intra Clinic of Phantasms 1992]

- Giovanni Intra, ‘Subculture: Bataille, Big Toe, Dead Doll’, MFA dissertation, University of Auckland, 1993: 2.

- Giovanni Intra, ‘Discourse on the Paucity of Clinical Reality’, Midwest, no. 7 (1995): 39–43.

- Ibid., 40.

- Giovanni Intra, ‘Studies for the Disarticulation of Disease’, Everyday Pathomimesis (Christchurch: University of Canterbury School of Fine Arts Gallery, 1995). np.

- Barbara Blake, ‘Giovanni Intra: Germ-Free Adolescence’, Art New Zealand, no. 70 (1994): 72.

- William McAloon, ‘The Self and Other Inventions’, The Chartwell Collection (Auckland: Auckland Art Gallery, 1996), np.

- Giovanni Intra ‘Mental Health in the Metropolis,’ Midwest, no. 6 (1994): 39–40. Giovanni Intra, ‘A Case History: Tainted Love’, Tainted Love (Auckland: Sue Crockford Gallery, 1994), np.

- Planet 13, Winter 1994: 71.

- I must apologise for errors in the Nine Lives catalogue, where I fancifully imagined that Intra’s vandalised technologies included watches and miscatalogued The Way Doctors See as How Doctors See, etc.