(with Christina Barton, Wystan Curnow, and John Hurrell) Action Replay, ex. cat. (New Plymouth: Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, 1998).

Action Replay revisits a time and a milieu of radical art practice without parallel in this country’s art history. 1970s post-object art broke with painting and sculpture as it had been practiced and set the precedents for much of the art which followed. And yet the works in this exhibition are largely unknown to the majority of today’s art audience. This is largely due to the poor representation of post-object art in collections and to its inadequate coverage in the history books. With works assembled in the main from the artists’ own collections or remade for the occasion, Action Replay recovers a crucial chapter in the history of contemporary New Zealand art.

Post-object art is represented here broadly, but not systematically. Action Replay presents works by more than twenty artists in a sequence of curatorial sketches at Artspace and the Auckland Art Gallery and a consolidated presentation at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. This is not an historical survey: each sketch proposes a distinctive but characteristic mix of media and subject rather than a chronological or thematic moment. Off setting such economies is a display of documentation from the period from the archives of the Auckland City Art Gallery and a forthcoming catalogue which fully backgrounds the exhibition.

The 1970s was the decade in which the elements of the contemporary art scene as we know it emerged and began to link up. The period saw the development of an art market, the creation of a national infrastructure of public galleries committed to contemporary art, the birth of local art magazines and art criticism, and the emergence of university art-history departments. While post-object art made a significant contribution to this nascent system, it also existed at one remove. Partly, this was because it took issue with aspects of the art system, and, partly, because it possessed the independent energy and coherence of an art movement. The space this critical distance represented was to eventually to take the form of collectives like the Artists’ Co-op with its woolstore in Wellington, an early artist-run space, and From Scratch.

The term ‘post-object’ defined the new practice by negation, indicating a desire to avoid the formal and political compromises that late modernist painting especially seemed mired in, but it also suggested, by inference, the copious bag of new materials, media, and approaches—installation, performance, photography, video—it broke open. Elsewhere, this art was called post-minimal art, conceptual art, or arte povera. Yet, none of these terms does justice to the startling and exhilarating expansion of the field of the visual arts that took place during this time, or to the variety of new subjects or the freshness and directness of the modes of address that characterised the new work.

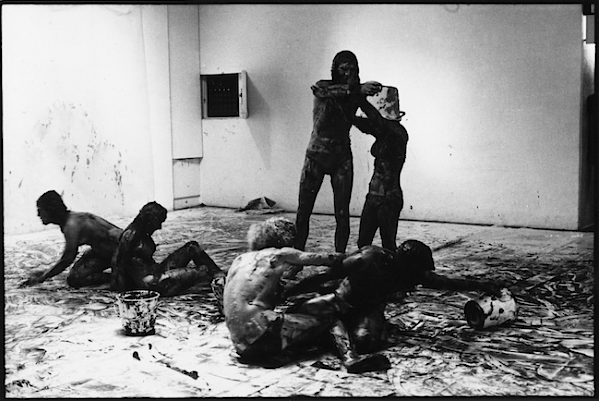

Typically, the art of Action Replay tends to present as much as represent the world. In place of an inert picturing of things, ideas, events, we have an art which often just situates or re-stages them in their actuality. Adrian Hall arranges concrete foundation blocks in a gallery space. Colin McCahon’s Blind is literally painted on canvas blinds. Performances by Andrew Drummond, Peter Roche, and Bruce Barber are real events documented and represented as video or slides, while John Lethbridge’s photographs are like stills from such performances. The environments of Jim Allen and Leon Narbey are performative in another way: the viewer’s own movement activates sounds or lights. And there are works in this show which are literally sensational: that emit real light (Jim Allen), that produce real sounds (Billy Apple/Annea Lockwood), that generate actual heat (Roger Peters). Either way, the physical body is a measure or an index, and sometimes a highly visceral one, of not only of actuality, but also of subjectivity and the social. Although the conceptual, language-based works of Terrence Handscomb, Mel Bochner, and Betty Collings present themselves as more cerebral than physical, they too are concerned with the body and with actualising the processes of their making. The words, numbers, and symbols of these notations and diagrams present language in action. So, there are common features to post-object work despite the striking variety of forms, subjects, and media.

The major bases of the post-object scene were the art schools, especially Elam School of Art at Auckland University during Jim Allen’s tenure as Head of Sculpture, and, to a lesser extent, Ilam School of Art at the University of Canterbury under Tom Taylor. Largely through the bold efforts of John Maynard as the first director of New Plymouth’s Govett-Brewster Art Gallery and then as exhibition officer at Auckland City Art Gallery, and later Ian Hunter, Nick Spill, and Andrew Drummond at Wellington’s National Art Gallery, the public-gallery system served as a significant if occasional venue for post-object projects. Other public galleries, such as Manawatu Art Gallery under the directorship of Luit Bieringa, were occasional players. A few dealers like Auckland’s Barry Lett Galleries (later RKS Art) were also important. Commonly, projects of the era critically addressed the exhibition site, challenging the physical and curatorial limits of orthodox gallery spaces or appropriating non-art sites, like Mount Eden crater, Bledisloe Place, Cathedral Square, the abandoned Ngaraunga meatworks, and Epsom Showgrounds, incorporating aspects of such sites into the work.

The scene was stimulated and informed by a small but steady flow of visiting artists from Britain and North America. Jim Allen was instrumental in bringing to Elam, as visiting teachers, a number of young sculptors with very current information, like John Panting (an expatriate), Adrian Hall, and Kieran Lyons. Added to that was the return as a student of Philip Dadson following a stint with Cornelius Cardew’s London Scratch Orchestra. Ian Hunter came out from the UK; Andrew Drummond returned from Canada and a meeting with Joseph Beuys in Edinburgh. Billy Apple, then based in New York, made two substantial visits involving many exhibitions, before returning here permanently in the 1980s. Darcy Lange made a return visit. As elsewhere in the late 1960s and early 1970s, universities were hothouses of creative and political action, with a generation of highly precocious students coming out of the art schools, Bruce Barber, Maree Homer, Christine Hellyar, and Roger Peters among them.

Crucial as all the input of visitors was to the independent energy and coherence of the post-object scene, the coming and going was also a measure of its instability and impermanence. The small scale of the New Zealand art scene and the difficulty of sustaining a post-object practice took its toll: some artists left the country, some gave up art altogether. As Action Replay shows, post-object art nevertheless captured the intellectual high ground of the period and displayed a creative engagement with international contemporary art practice that only in the 1990s have we come to take for granted.

.

[IMAGE: Jim Allen]