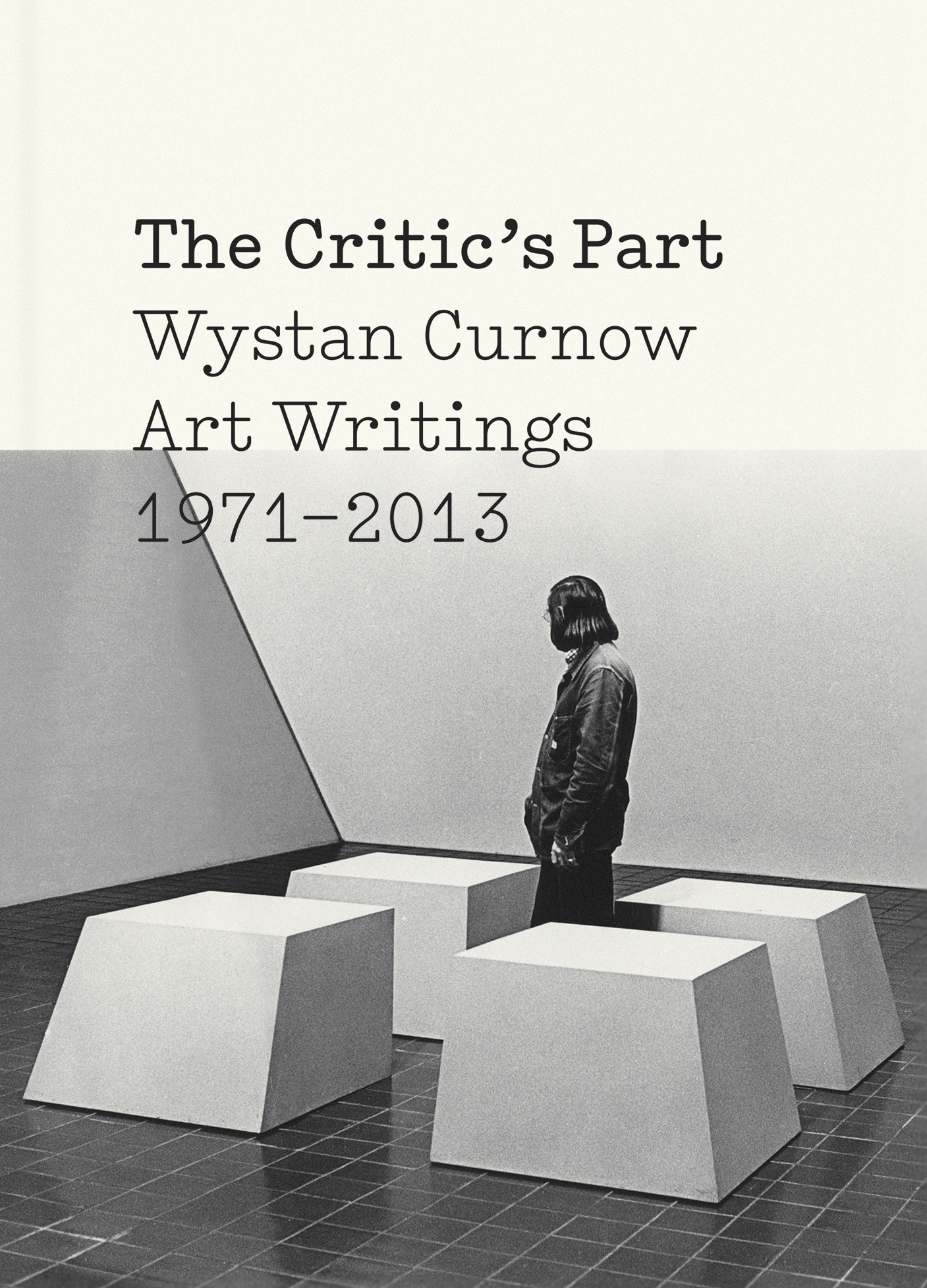

The Critic’s Part: Wystan Curnow Art Writings 1971–2013, ed. Christina Barton and Robert Leonard, with Thomasin Sleigh (Brisbane and Wellington: Institute of Modern Art and Adam Art Gallery with Victoria University Press, 2014). This is one of two introductions to the book.

Give me a place to stand and I will move the earth.

—Archimedes of Syracuse

•

Wystan Curnow has been writing on art for half a century. His singular contribution to New Zealand art and art history is keyed to a crucial fact: he left New Zealand and came back. In 1963, Curnow travelled to the US to do a doctorate in American literature. There, he was exposed to countercultural ferment, to new thinking in the humanities, and to the latest art. Going to the US unmoored Curnow from his peers in New Zealand, setting him on another intellectual trajectory. Returning home in 1970, he would re-enter an art scene that, despite its having grown considerably, he could only see as small, isolated, and provincial. Here, painting was the dominant medium, landscape the dominant subject, and national identity the dominant idea. However, the country’s painting mainstream was being challenged on either flank by forms of ‘internationalism’; firstly, and somewhat belatedly, by modernist abstract painting, and, secondly, by the emergent, and more internationally current, ‘post-object art’ (as it was known in Australasia). Curnow would align with both.

Overseas experience gave Curnow a distinct perspective on the vices and virtues of New Zealand art and a hefty critical toolbox with which to address them. He was not a generalist or a jobbing critic. He wanted to say something new, not simply ‘fill in the cultural space already known’, as he later put it.1 He wrote on relatively few artists, but repeatedly and at length. He always had an agenda. He wanted to change things: to give New Zealand art a wider context and to up-skill the culture so that it could better engage with and support what advanced artists were doing. He also had an approach: he experimented with writing styles, seeking to develop new forms of art writing to meet the ambitions of new forms of art. While his criticism certainly moved with the times—responding to and participating in big paradigm shifts (formal abstraction, post-object art, postmodernism, feminism, biculturalism, and globalisation)—it nevertheless remained surprisingly consistent across the decades. Curnow generated a unique, serious, ambitious body of art writing, one that differs, in content and form, from what other New Zealand art critics produced. A project underpins it all.

•

In 1939, Wystan Curnow was literally born into New Zealand’s art and literary scene. His father was poet Allen Curnow, a leading figure in New Zealand literature, his mother, Betty, was an artist, and they named Wystan after British poet W.H. Auden. Curnow’s Christchurch childhood home was a meeting place for intellectuals, writers, and artists, including Rita Angus and Theo Schoon. (Angus drew Wystan as a child and painted the iconic portrait of his mother in the Auckland Art Gallery collection). The Curnows moved to Auckland in 1951, when Allen accepted a lectureship in the English Department at the University. While at secondary school, Wystan was a regular visitor to Auckland City Art Gallery, and took painting classes there under Colin McCahon, a family friend from Christchurch.2 Later on, as an undergraduate, he would drop by to chat with Director Peter Tomory and his staff in the lunch room.3 Curnow studied English Literature and History at the University of Auckland, completing his BA in 1960 and his MA with first-class honours in 1963. Curnow’s earliest art writings include reviews of dealer shows by Milan Mrkusich and McCahon, published in 1961.

Curnow chose to do his doctorate in the US, rather than England. Working on American literature was a mark of his attraction to the new world over the old, and to postcolonial rather than colonial literatures. Leaving in 1963, he based himself at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, where he studied under Morse Peckham. Despite being a scholar in the traditional areas of romanticism and aesthetics, Peckham developed a new approach, grounded in semiotics, behaviourism, linguistics, anthropology, and art history. His ‘post–New Critical and post–New Left theoretical approach’, as Curnow described it,4 offered a new account of literary and cultural change. Peckham’s controversial book, Man’s Rage for Chaos: Biology, Behaviour, and the Arts, which advanced a behaviourist theory of art making, was published in 1965, while Curnow was still his student. The book provided Curnow with a theoretical overview and useful terminology. Crucial were the division of labour between ‘primary producers’ (artists) and ‘secondary’ ones (such as critics), the centrality of the ‘art perceiver’s role’, the notion of art as ‘problem solving’, and ‘psychic insulation’ (the crucial condition artists require in order to produce important new work).

It was a thrilling time to be in the US—a moment of cross-referenced artistic, political, and cultural upheaval. The civil-rights movement and anti-Vietnam War protests were in full swing (Curnow arrived in Philadelphia as Martin Luther King Jr. made his historic march on Washington). Just as influential as his studies would be Curnow’s immersion in the contemporary-art, music, and poetry scenes of Philadelphia and New York, which was less than two hours from Philadelphia by train. Already an aficionado of American jazz and abstract expressionism, Curnow threw himself into the big city’s cultural life. Although he spent time in museums, he gained his real art education in dealer galleries, grounding himself in what would prove to be the most advanced art of the time: pop art, minimalism, conceptualism, colour-field painting, and kinetic and light art—the new forms into which modernism was evolving.

In 1967, Curnow completed his PhD on Herman Melville’s late, proto-modernist poetry and took a job teaching at the University of Rochester, in upstate New York. There, he became embroiled in the kinds of political protests that were erupting on campuses across the US. In 1970, seeing no signs of the turmoil abating, with a wife and young family, and a desire to reconnect with home, Curnow returned to take up a position in the English Department at the University of Auckland, where his father was still teaching.

While in the US, Curnow had kept abreast of New Zealand art, especially through visits from friends such as Hamish Keith, Don and Judith Binney, and Jim Allen (Head of Sculpture, Elam School of Fine Arts, University of Auckland). On his return, Curnow was rapidly recruited as a critic, and was encouraged in that role by Allen and Tony Green (the inaugural head of Art History, University of Auckland, who had recently arrived from Edinburgh). The Critic’s Part opens with two reviews of 1971 Auckland City Art Gallery exhibitions that anticipate the directions in which his criticism would move. In one, Curnow enthuses over a touring show by celebrated American abstract painter Morris Louis; in the other, he critiques the curatorial sloppiness of Young Contemporaries, a local young-artists survey show.

In the early 1970s, New Zealand art was largely a painters’ scene. A small market had developed and a few painters were becoming household names. After what he had experienced in the US, Curnow found much of the work unremarkable, although he remained a huge McCahon fan. Instead, he was drawn to the alternatives, to modernist abstraction, and, even more, to post-object art. The fledgling post-object-art scene, centred on Allen’s Sculpture Department, would become his focus. Allen had recently returned from his 1968–9 sabbatical trip to Britain, France, Mexico, and the US (where he had stayed with the Curnows). Fired up by what he had seen, he was fostering experimental art with his students. Curnow responded enthusiastically. This was the kind of work he recognised as contemporary, being akin to the context-sensitive, ephemeral, conceptually driven work he had seen in the US. Curnow attended art-crit sessions at the School and quickly became the ‘house critic’ of the movement.

In the 1970s, Curnow embarked on a mission to raise the stakes for serious writing on art and literature in New Zealand. He attacked the art and literary establishments, charging them with a lazy deferral to romantic, expressive, and biographical modes of analysis, and called for a deeper engagement with new forms and ideas, particularly those emanating from the US. Recognising a lack of venues for sustained commentary, he created an opportunity for himself and others to publish longer pieces by editing the book Essays on New Zealand Literature (1973). Alongside contributions by Terry Sturm, Robert Chapman, and others, Curnow offered his own manifesto-like essay ‘High Culture in a Small Province’, a trenchant diagnosis of the limitations of the local scene.

‘High Culture’ didn’t pull its punches. Curnow was not afraid to describe the scene as hamstrung by smallness and lack of specialisation. Quoting Peckham, he characterised high culture as concerned with ‘discovering and creating problems’: ‘it contains in solution innumerable ambiguities and ambivalences and puzzles and problems’. (Later, he would put his own spin on it, describing it as the pursuit of ‘new forms of thought and feeling’.) In ‘High Culture’, Curnow complained that New Zealand’s cultural middlemen (its critics and commentators) dragged art down by seeking to reduce the distance between art and the public, when they should be seeking to increase that distance by generating the ‘psychic insulation’ that would enable artists to be ambitious, free of the restraints placed on them by an uninformed, unappreciative society. The essay did not win Curnow many friends, but its combative, elitist tone was a telling marker of the end of New Zealand art’s nationalist era.

‘High Culture’, and its 1975 companion piece ‘Doing Art Criticism in New Zealand’, made the case for serious criticism as a necessary component of a functioning art scene. If these essays established a job description for the critic, Curnow’s other writings show him seeking to fulfil it. He wrote short-form reviews for mainstream magazines, such as the Listener and Arts and Community, and longer pieces on Billy Apple and post-object art for Auckland City Art Gallery Quarterly. For the new glossy, Art New Zealand, he wrote essays on McCahon, Len Lye, and Max Gimblett, and ‘Art Places’ (a series of diaristic accounts of his art adventures in New York, Toronto, and Sydney).

Curnow had a distinctive voice. He could move back and forth between an essayistic style instilled by his academic training and a colloquial reportage style informed by the immediacy and directness of New Journalism and New American Poetry.5 His writing offered a vivid account of what it meant to be exposed to new kinds of art in the here and now. Curnow wanted to get past habitual approaches. In experimental texts such as ‘Mt. Eden Crater Performance’—a stream-of-consciousness, phenomenological account of a 1973 Bruce Barber performance composed in situ during the event—he bypassed standard critical approaches. His writing suggested a rejection not only of New Zealand amateurism but also of the ‘frame lock’ and ‘tone jam’ of American academics (including Peckham).

In 1976, ‘Mt. Eden Crater Performance’ was published in New Art: Some Recent New Zealand Sculpture and Post-Object Art, which Curnow edited with Jim Allen. Perhaps Curnow’s most substantial output in the 1970s, this book documented moves in New Zealand sculpture since the late 1960s. Featuring the work of Allen, his students Barber, Philip Dadson, Maree Horner, and Leon Narbey, plus sculptors Greer Twiss, Kieran Lyons (visiting from Britain), and Don Driver (the only artist not based in Auckland), it was the principal published resource dedicated to ‘the movement’. On every level, New Art declared its difference: by including relatively unknown artists (students!) alongside established ones, by incorporating visitors, by refusing exegesis in favour of experimental reportage and ‘documentation’, and by treating the printed page as a kind of ‘artist’s space’. New Art set out to mirror post-object art and to establish an alternative New Zealand art canon, with the expatriate innovator, Len Lye, as its touchstone.

Also in 1975, another New York–based expatriate artist, Billy Apple, visited New Zealand. On the fly, he produced a series of site-specific shows in galleries throughout the country. Apple typically explored the spaces by subtracting things from them; for instance, he cleaned wax off floor tiles at Auckland City Art Gallery. New Zealand was not ready for such conceptualism. To many, it seemed that the artist was a charlatan, exhibiting empty galleries. The ensuing bad press certainly confirmed Curnow’s arguments about New Zealand art’s lack of psychic insulation. Curnow addressed this directly in an essay in Auckland City Art Gallery Quarterly (‘Billy Apple in New Zealand’), where he analysed the media response before moving onto the work itself.

When Apple returned in 1979 to do a second string of shows, Curnow lent his services to the artist, managing the press, riding shotgun. In addition to keeping journalists off Apple’s back, Curnow became involved in making the work—a collaborator. He helped conceptualise, produce, and mediate the shows, providing explanatory wall texts that effectively became part of the work. If Curnow had suspended criticality in order to write his ‘Mt. Eden Crater Performance’ text, his collaboration with Apple further blurred the boundary between artist and critic, countering the idea of the critic as a neutral, independent voice.

•

The early 1980s saw a sea change in art—postmodernism. At the University, Curnow was teaching contemporary American poetry with Roger Horrocks.7 Their students Alex Calder and Leigh Davis were eager conduits for the new ‘theory’. Curnow and Horrocks worked with them, and with fellow poets Tony Green and Alan Loney, to produce the short-run postmodernist magazines Parallax, And, and Splash.

Published in the first issue of Parallax, Curnow’s essay ‘Post-Modernism in Poetry and the Visual Arts’ (1982) was the first local attempt to systematically address the change. Curnow’s thinking developed not from continental philosophy (as would become the norm) but from American literary and art theory; he drew heavily on writers, theorists, and artists whom he had been exposed to in the US in the 1960s. Curnow identified postmodernism with those who disavowed romanticism’s metaphysical tenor in favour of direct engagement with material reality. This ‘new stance towards reality’, he argued, gave rise to new forms of art that reject the expressionist transformation in favour of procedures, such as measurement and serial arrangement, which accede more fully to that which is ‘given’. Curnow ended up asserting the ‘linguistic’ basis of contemporary representations (the materiality of signs) and warned against delving beneath the surfaces to lay claim to deep, personal, or transcendent meanings.

The essay did not get picked up in New Zealand; it would not be influential. In fact, the ironic appropriation that would become postmodernism’s hallmark suggested a break with the blunt literalism of the very forms of art practice Curnow celebrated in his essay. The ‘Post-Modernism’ essay was premature. It was written before the influence of L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poetry and post-structuralism had properly worked their way into Curnow’s writing. However, now, the piece appears more prescient. As postmodernism has become a disregarded term, and with growing interest in the art of the late 1960s and 1970s, it helps us to understand how postmodernist sign-play could develop out of minimalism’s and conceptualism’s literalness, rather than against it. Curnow constructed a bridge between conceptual art and what followed.

In ‘High Culture’, Curnow had criticised the versatility—the lack of specialisation—demanded by a small scene. However, he would go on to wear a range of hats. Curnow’s engagement with the international art world made him a powerful figure at home. He became the go-to guy on New Zealand art, contributing to international art magazines such as Artforum and Studio International. He became involved in exhibition making, as New Zealand commissioner for the 1982 Biennale of Sydney and curator of I Will Need Words, an exhibition of McCahon’s word and number paintings for the 1984 Biennale. After meeting Edinburgh gallerist Richard Demarco at Wellington’s F1: New Zealand Sculpture Project, he arranged for I Will Need Words to travel to the Edinburgh Festival, where it was accompanied by another show, ANZART in Edinburgh (1984), whose New Zealand half he also curated. As a curator, he would go on to be associated with the rise of discursive ‘theme shows’ in the postmodern late 1980s and 1990s, with shows like Sex and Sign (1987). In addition to enjoying long-term relationships with many New Zealand art museums as a writer and curator, Curnow also helped found New Zealand’s first funded ‘alternative space’, Auckland’s Artspace, serving as its inaugural chair, and he would later become a Len Lye Foundation Trustee. All this time, he was also an active poet. While this diverse, DIY activity might seem to fly in the face of the disdain for jacks-of-all-trades that Curnow had expressed in ‘High Culture’, all his engagements were strategic—designed to advance the cause of high culture.

•

‘Be honest, have you ever heard of New Zealand art?’, Curnow wrote in Studio International in 1984.8 He was never afraid to acknowledge New Zealand art’s marginality, and yet his internationalism was complex and nuanced.

Curnow always tried to put New Zealand art into an international context. The artists he celebrated tended to be internationalist in their outlook or situation. He reclaimed expatriates like Apple, Lye, and Gimblett. Even when he wrote on McCahon, an artist synonymous with New Zealand, he put him in the company of overseas figures, like Barnett Newman, Jasper Johns, Julian Schnabel, and Imants Tillers.9 Curnow’s internationalism was enabled by regular travel. His long tenure at the University enabled him to leave on sabbaticals and for conferences. He regularly went to the US, and, from the early 1980s on, to Australia and Europe as well. It was during his visits to New York in the 1970s (some documented in ‘Art Places’) that he became a fully fledged emmisary and art bagger, engaged and at large, doing the business. On his travels, Curnow built a network of collaborators and friends in high places, including Jacki Apple, Charles Bernstein, René Block, Rudi Fuchs, Jan Hoet, Thomas McEvilley, Terry Smith, and Lawrence Weiner.

While he explored ways to write New Zealand art into the international context, Curnow was also aware of the limitations and presumptions of those at the centre. His writings often drew attention to the power dynamics underpinning international exhibitions (Te Maori being a compelling example). As much as he argued a wider context for New Zealand art, he also sought a wider context for international art. He plugged into the ‘dispersed centres’ of what would come to be known as ‘global conceptualism’—places like rural Mildura in Australia, Halifax in Canada, Edinburgh in Scotland, and, later, numerous hot spots in Eastern Europe. Curnow’s internationalism was self-consciously and often assertively provincial. While he read New Zealand art from the viewpoint of the centre, he also read the art of the centre from an antipodean perspective.10 This richness was evident in the way he simultaneously argued McCahon into the mainstream of twentieth-century Euro-American modernism and asserted his remoteness from it. It also made him the perfect commentator on Australia’s leading appropriator, the diasporic Tillers.

It is interesting to contrast Curnow’s internationalism with Francis Pound’s. In the 1980s and 1990s, both critics advocated internationalism, but each meant something different by it. Emerging ten years after Curnow, in the postmodern 1980s, Pound was aligned with the market mainstream, and almost exclusively focused on painting, while Curnow was grounded in post-object art. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Pound’s taste was current and was hugely influential on the new collectors (via Auckland’s Sue Crockford Gallery), while Curnow’s seemed grounded in the late 1960s and 1970s. However, times change. Today, from our post-medium vantage point, and with a revival in interest in experimental art of the 1960s and 1970s, Curnow’s internationalism has the greater purchase and currency.

While Curnow was critical of New Zealand art’s nationalism, he was always sensitive to questions of place, of location. While he rejected the expressive-realist tradition (which promoted landscape painting as a window on the world), he was enthusiastic about conceptual artists who drew on the alternative tradition of cartography to address place. Curnow liked maps because they sidestepped the romantic investments and epistemological presumptions of landscape painting by foregrounding the use of arbitrary signs and cultural conventions. In 1989, Curnow curated a theme show for the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, Putting the Land on the Map: Art and Cartography in New Zealand since 1840. It juxtaposed historical material (maps and early topographical watercolours) and Maori ‘oral maps’ with works by contemporary New Zealand artists (Andrew Drummond, Derrick Cherrie, Philip Dadson, John Hurrell, Tom Kreisler, Ruth Watson, and others). The show argued that mapping codes tell us less about locations than about ourselves, our ‘prospects’ and ‘projections’, in the process demonstrating how Pakeha overwrote Maori in staking their claim to this place.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, biculturalism complicated the nationalism–internationalism debate. Maori issues had first entered Curnow’s work in the 1980s, when he wrote on McCahon’s works with Maori themes. Although he had no interest in the first generation of contemporary Maori artists, in the 1990s, Curnow would begin to write on the new generation, notably Jacqueline Fraser and Michael Parekowhai, and would work on and around Leigh Davis’s 1998 art/poetry project Station of Earth-Bound Ghosts, which celebrated Maori rebel leader Te Kooti. Curnow folded biculturalism into his increasingly postcolonial internationalism. But, if Putting the Land on the Map co-opted Maori concerns in contesting the old Pakeha nationalism, elsewhere biculturalism was being conscripted into a new kind of neo-nationalism, typified by the country’s combined National Art Gallery and Museum, Te Papa.

After Putting the Land on the Map, art and cartography remained a focus for Curnow, spawning conference papers, articles, and, ultimately, the book chapter, ‘Mapping and the Extended Field of Contemporary Art’. This interest was timely, being keyed to the art world’s ‘global turn’ in the late 1980s and 1990s. With John McCormack (then Director of the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery), Curnow developed a new project to address this turn from an antipodean standpoint—Under Capricorn. In 1994, they organised the conference Under Capricorn: Is Art a European Idea? in Wellington. Speakers included Thierry De Duve, Thomas McEvilley, and Marian Pastor Roces. (Curnow’s paper, on Gordon Walters and Jacqueline Fraser, is published here for the first time.) Two years later, they followed up with an exhibition, curated by Curnow and the Stedelijk Museum’s Dorine Mignot. Under Capricorn: The World Over showcased artists articulating the global turn, placing New Zealand artists, including McCahon and Parekowhai, alongside artists from Australia, the US, Europe, and Japan, linking them through such shared themes as ‘nexus’, ‘panorama’, and ‘globe’. The show was staged on both sides of the world simultaneously, at City Gallery Wellington and the Stedelijk in Amsterdam, with the same artists showing in both places. It was a refutation of established nationalist ways of thinking and working as well as a critique of the geopolitics of the now commonplace international biennale.

•

In the late 1990s, Curnow began to consolidate, writing and editing monographs on individual artists. He completed books on Tillers, Gimblett, Lye, and Stephen Bambury (a McCahon biography is still in the pipeline). He also began to write texts reviewing his previous work and concerns, clarifying, upgrading, and polishing his project (for instance, ‘Writing and the Post-Object’).11 Written especially for this collection, ‘High Culture in a Small Province: Further Thoughts 1998–2013’ is a great example of this, with Curnow revisiting his original ‘High Culture’ essay four decades on.

In ‘Further Thoughts’, Curnow’s focus is cultural and political economy. When he wrote ‘High Culture’, things were very different. New Zealand was economically and culturally isolated and New Zealand art was asserting a national identity in the face of that isolation. The country was also still constructing an infrastructure for high culture. However, today, New Zealand enjoys a well-developed art infrastructure and our artists participate in a global art world, with offshore residencies and the Venice Biennale. The change is tied both to internal developments in the New Zealand art scene and to external developments in the wider art world linked to globalisation and neo-liberalism.

Curnow’s relation to neo-liberalism is complex. On the one hand, he is a classic left-winger. His writings are politically aware, being peppered with references to social-justice issues (such as the Springbok tour and Maori land rights) as well as to art politics. In ‘ANZART as Is’, for instance, he exposed vested commercial interests underpinning a touring blockbuster exhibition, and, in ‘Te Maori and the Politics of Taonga’, he addressed the deal with the devil that Maori struck by getting into bed with the show’s sponsor, Mobil. On the other hand, Curnow was always an unapologetic elitist, dismissive of both populism and preachy didacticism in art. In ‘High Culture’, he argued that the public had little chance of genuinely appreciating the best art, and quoted Peckham saying that the best art ‘maintains itself by alliance with political power, social status, and wealth’.12

Neo-liberalism has transformed New Zealand culture, changing what and how New Zealanders think about all manner of things, including art and its institutions. In New Zealand, the changes can be traced back to 1984—when a new Labour government banned nuclear ships but also deregulated the economy and flogged off state-owned assets, in the process collapsing the commonsense distinction between left and right wing. By 1984, Billy Apple, ever alert to the Zeitgeist, had already shifted to painting and was making works that reflected on and celebrated (rather than critiqued) the emerging art market—particularly the good names of collectors. As Apple became something of a court painter to the new elites, Curnow, as his apologist, went along for the ride. In 1985, the fashion magazine ChaCha photographed Curnow (in aviator shades) and Apple standing outside Auckland City Art Gallery with Apple’s Porsche; they looked triumphant—as if they were the landlords. But, there must have been a dash of irony, because, around the same time, Curnow was also writing up Bruce Barber’s Marxist critiques of American right-wing ideology (‘Bruce Barber’s “Vital Speeches”’).13 You might say Curnow was having a bob each way, but, actually, he was—self-consciously—surfing the number-one antimony of his time (and place).

By the 1990s, art museums were scrambling populism and elitism, pursuing bums-on-seats (customers) with bread-and-circuses and pursuing corporate sponsors (stakeholders) with cocktails. On the one hand, art museums were being rethought as a broad-audience entertainment option; on the other, corporates were drawn to contemporary art, believing its speculative activity mirrored their own. Things looked rosy: the infrastructure had expanded, art museums were more popular than ever, and New Zealand artists were being plugged in internationally. However, art was also being co-opted by cultural, corporate, and creative-industries rhetorics, undermining the high-culture project. Curnow was well placed to observe the changes and to understand and warn of their implications. He would also have access to new tools. In ‘Further Thoughts’, Peckham gives way to Jacques Rancière (The Politics of Aesthetics, 2004) and Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiappello (The New Spirit of Capitalism, 2005).

In the 1970s, Curnow had resisted New Zealand art’s nationalism, casting it as parochial. However, in ‘Further Thoughts’, he implicitly counters its new self-congratulatory internationalism. The piece concludes by discussing a work that responds to the merging of tourism and entertainment industries, Cruise Line, by our young, internationally hot-right-now, expatriate artist, Simon Denny. I imagine that, back in the 1970s, Curnow would have been anxious to plug Denny into the international discourse; however, Denny is already plugged into it (indeed, he is better known and understood offshore than in New Zealand). So, perhaps perversely, Curnow instead writes Denny into an obscure local narrative (or, more correctly, he uses Denny’s work to construct that narrative for the first time). He links Cruise Line to a work produced in New Zealand in the 1970s by the visiting British artist Kieran Lyons and to works produced overseas by expatriate New Zealanders, Bruce Barber, Darcy Lange, and Michael Stevenson. All these works address capitalist rhetoric, presaging Denny. In forging this counter-intuitive canon, Curnow creates a defiantly local context for our currently most internationally successful artist, while nevertheless resisting the way the local is typically conceived (as New Zealand artists living in New Zealand making works for New Zealanders). In this, his last word (for the moment), Curnow presents himself as an internationalist from here, an antipodean internationalist.

•

Everything contains its opposite. Globalisation makes the world bigger and smaller; it promotes difference while extinguishing it; it embraces previously marginal ‘voices from the wilderness’ but weaves them into the rich tapestry of empire. New Zealand art has become part of an international art world, but it’s a very different international art world to the one that shaped Curnow in the US in the 1960s. His writings help us to understand how New Zealand art evolved out of its inward-looking nationalism (the early days of the mission) to take its place in the brave new global art world of the twenty-first century. Indeed, his writing enabled that shift. But, as much as Curnow wants New Zealand art to be part of a bigger discussion, he refuses to sacrifice place, recognising that his unlikely location provides insights into and leverage upon the dynamics of ‘international art’ and ‘world art’. Curnow’s self-consciousness—and his commitment to putting his own practice into a historical context—makes his back catalogue of writings of singular value in understanding our current moment; in tracking how we got here and in imagining where to next.••

- Wystan Curnow in conversation with the author, January 2014.

- Auckland City Art Gallery became Auckland Art Gallery in 1996.

- See Curnow’s descriptions of this time in Thomasin Sleigh, ‘Neither Here Nor There: The Writing of Wystan Curnow 1961–1984’, unpublished MA Thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, 2010, especially 7–14.

- Wystan Curnow, quoted in ibid., 35.

- Before he left for the US, Curnow was an avid reader of Evergreen Review and of Grove Press and City Lights books. At that time, little contemporary writing was offered to students, either in New Zealand or the US. When he returned to Auckland, Curnow joined Roger Horrocks in teaching Horrocks’s already-established course in American poetry. Together, they brought the course’s focus increasingly into the present. By the 1980s, they were bringing American poets—including Charles Bernstein and Jackson MacLow—to New Zealand to guest lecture in their course, which had few, if any, parallels, even in the US.

- Charles Bernstein, ‘Frame Lock’, in My Way: Speeches and Poems (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), 90–9.

- Curnow and Horrocks did their MAs together in Auckland, and Horrocks also did post-grad studies in the US—at Berkeley.

- See Wystan Curnow, ‘ANZART as Is’, Studio International 197, no. 1005, Summer 1984: 40.

- Curnow has also written on international artists, including On Kawara, Lawrence Weiner, and Vito Acconci. His involvement with the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poets is longstanding.

- Sleigh highlighted this in titling her thesis ‘Neither Here nor There’.

- This book is itself a contribution to that reflective process.

- This is a direct quote from Peckham. Wystan Curnow, ‘High Culture in a Small Province’, in Essays on New Zealand Literature, ed. Wystan Curnow (Auckland: Heinemann, 1973), 155.

- Curnow also enjoyed a close friendship and working partnership with poet/critic Leigh Davis, who had been one of his students in the English Department and an editor of And. After university, Davis became a money man with Fay Richwhite, where he was involved in the privatisation of New Zealand Rail in the 1980s. By the late 1990s, Curnow was working on Davis’s project Station of Earth-Bound Ghosts, celebrating Maori rebel leader Te Kooti. Davis also named his private-equity fund, Jump Capital, after one of Curnow’s favouite artists, Colin McCahon. For Davis, Te Kooti, McCahon, and merchant banking were not odd bedfellows. Davis challenged any assumption that his art and business practices were contradictory. See Nevil Gibson, ‘Leigh Davis: Avant-Garde in Business, Arts, Adventure’, National Business Review, 9 October 2009.