.

There’s a lot of clamour around ‘art history’ right now. On the one hand, universities are cutting art-history departments—it’s part of the neoliberal purge of the humanities, we’re told. On the other hand, art history is under attack from the left—as a bastion of crusty white privilege. Of course, when people talk about ‘art history’, they are often talking about very different things. For many people, ‘art history’ conjures up notions of the canon, and the image of Lord Kenneth Clark in his tweed jacket fronting the 1969 BBC TV show Civilisation, laying out the Western high-art tradition. (I was six.) However, we tend to forget that, just three years later, in 1972, BBC2 screened John Berger’s Ways of Seeing—a Marxist-feminist critique of Civilisation. (I was nine.) When I started studying art history at the University of Auckland in the early 1980s (still a teenager), it was still all about the Western tradition (white males), and, to proceed to post-grad, you had to study a European language (French, German, Italian, or Spanish). However, all that was rapidly coming unstuck. A Women in Art paper was introduced (which I did), followed (after I left) by papers on New Zealand art, contemporary art, and Maori and Pacific art. Today’s art-history courses bear little resemblance to the one I did. Similarly, in my later life in art museums, art history would be always under scrutiny while being furiously transformed. For as long as I have been involved in it, art history has been in a state of perpetual and profound revision, philosophical and political expansion. Indeed, for me, art history is that business of rewriting. Art history may be, at once, the field and the game that’s played upon it; poison and cure, scapegoat and straw man. Pharmakon.

.

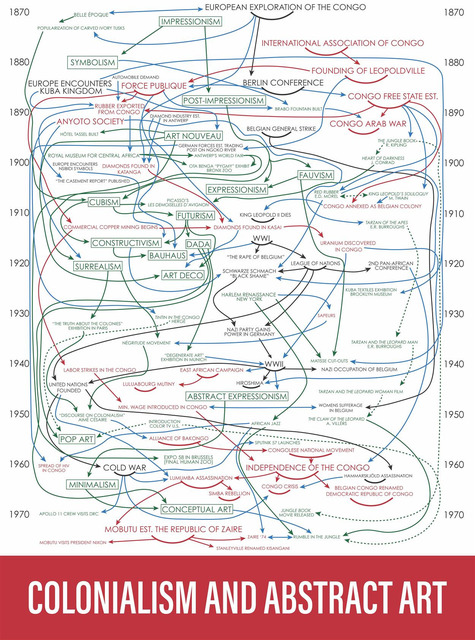

[IMAGE: Hank Willis Thomas Colonialism and Abstract Art 2019]

•