.

In a flurry of Covid-lockdown recreational decluttering, I came across a talk I gave almost twenty years ago. Long before I’d heard of Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, I was trying to explain art after Duchamp to some university law students. Looking back, the talk was absurdly ill-conceived for its audience. It’s a problem, neglecting your listeners to indulgently think out loud. Here it is:

.

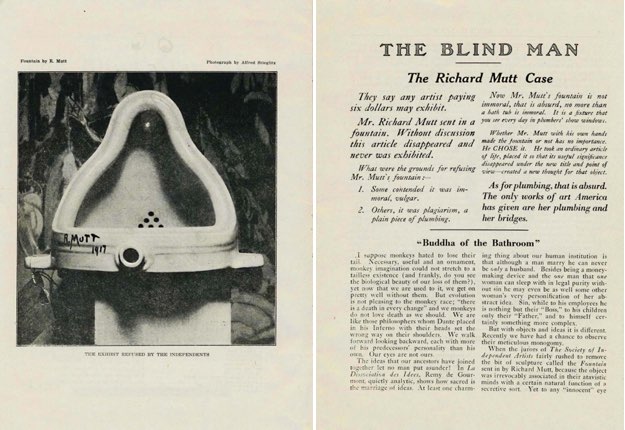

Marcel Duchamp made Fountain in 1917. It was a game changer. The French artist acquired a porcelain urinal, laid it on its back, titled it Fountain, and signed it ‘R. Mutt’, declaring it art. The work was rejected from a supposedly sympathetic, anything-goes, all-comers exhibition organised by New York’s Society for Independent Artists. They said anyone paying six dollars could exhibit, but Fountain tested even their limits. Perhaps they thought it was a prank; perhaps it was.

When Fountain was rejected, an anonymous article (likely penned by Duchamp) defended its status as art, arguing that ‘Whether Mr. Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under it under the new title and point of view—created a new thought for it.’ Of course, today, Fountain is not only accepted, it’s canonical. We live in a post-Fountain art world.

Before Fountain, art was different—it was a kind of thing. There were criteria—a traditionally grounded consensus about what art was, what forms it could take, why to do it and how. Back then, you could take an artwork out of an art context and still recognise it as art—it was clearly a painting, a sculpture, an etching, etcetera. But, when Fountain entered art, it changed everything. It signalled that being art no longer turned on an art object’s intrinsic properties, but on the position it occupied. It was art because it was in a gallery or an art magazine. Location, location. Fountain may have been iconoclastic, yet it bolstered the art institution. When art can take any form, the art institution becomes crucial in a new way, to assert and police what is art and isn’t. Now, the institution didn’t just recognise art status, it conferred it.

Fountain changed the art game, but it didn’t change it straight away. It took a while for its implications to filter through, and the Fountain idea has always faced resistance—still does. We have the Fountain idea of art, but it is everywhere attended—haunted—by the pre-Fountain idea. Some still want to think of art in old-school terms, praising beautiful, skilful, edifying art—‘good painting’—and dismissing lights going on and off. Curmudgeonly critics act as if Duchamp never happened. Pre-Fountain-idea art is still being made, but now the Fountain idea reframes it. There’s no way back.

What goes for art has changed, but ‘art’ includes what has gone for art in the past. In an art museum or an art-history book, we can move from a gilded Renaissance altarpiece (pre-Fountain) to Piero Manzoni’s tins of his own shit (post-Fountain) in a blink, and it’s all art, even as these works are premised on radically different, even contradictory, expectations as to what art can be. They are equally part of a tradition.

To address the implications of this, it’s useful to consider an insight from political science—anti-descriptivism. For descriptivists, names describe things. To be, say, ‘socialism’, a regime needs to have certain properties. If it once had them but lost them, it ceases to be socialism, even if it still bears the name. Anti-descriptivists go the other way. For them, names are proper and linked to their referents through ‘primal baptism’. Socialist regimes may evolve in all kinds of contradictory ways but remain socialist.

In his preface to Slavoj Žižek’s The Sublime Object of Ideology, Ernest Laclau takes this idea a step further: ‘What is overlooked, at least in the standard version of anti-descriptivism, is that this guaranteeing the identity of an object in all counterfactual situations—through a change of all its descriptive features—is the retroactive effect of naming itself: it is the name itself, the signifier, which supports the identity of the object. That “surplus” in the object which stays the same in all possible worlds is “something in it more than itself”, that is to say the Lacanian objet petit a: we search in vain for it in positive reality because it has no positive consistency—because it is just an objectification of a void, of a discontinuity opened in reality by the emergence of the signifier.’

This brand of anti-descriptivism offers a productive way to understand ‘art’. If the altarpiece and the tin of shit both belong to art, there’s something at stake in the name of art that exceeds its examples and transforms them.

•