.

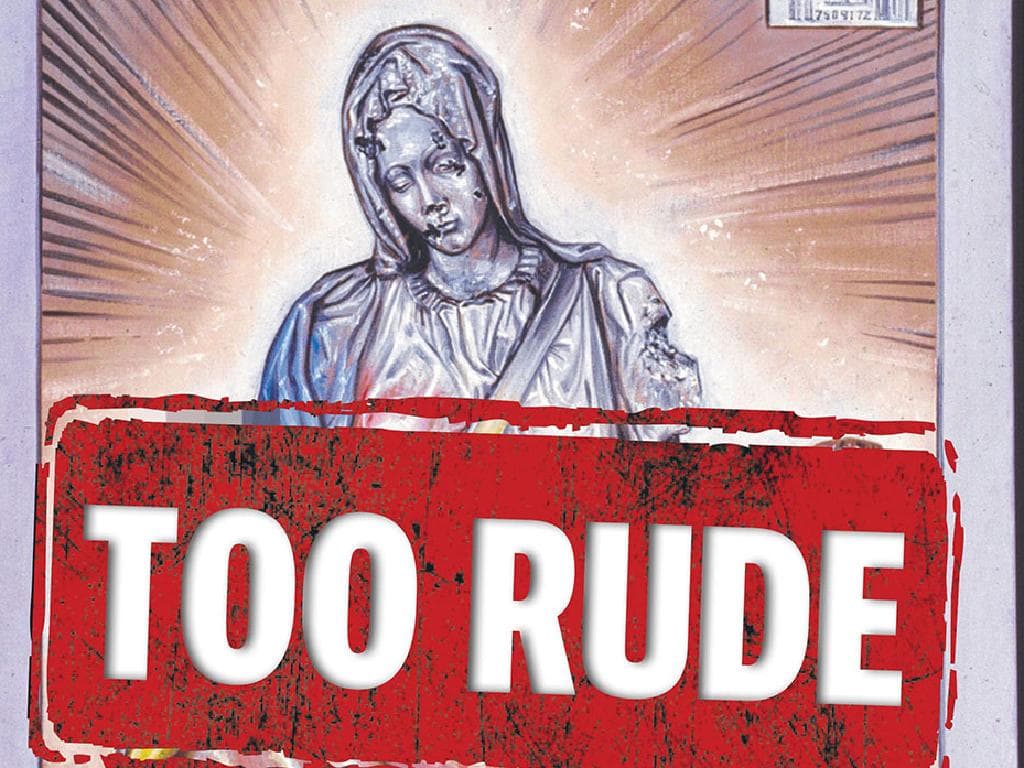

My friend Angela Goddard, Director of Griffith University Art Museum in Brisbane, is in hot water. Christians are attacking the Gallery for including Juan Davila’s 1985 painting Holy Family in its current show, and the media are all over it like a cheap suit. Davila’s work is based on Michelangelo’s iconic sculpture, the Pieta, which shows the Virgin cradling the dead, deposed Christ. In Davila’s painting, Christ’s body is replaced with a man-sized penis.

The media—as per usual—has amplified a storm in a teacup into a flood of biblical proportions. The rhetoric is ripe, the reports overblown. The idea—that Christianity and Christians are so fragile that such images need to be removed for their safety—is silly. No one is being forced to view the work. It’s in an off-off-Broadway, campus gallery, seen by a small art-world audience entirely familiar with such things—with trigger warnings added for anyone who isn’t. The claim that the Gallery shouldn’t show the work because the University gets millions from government is bogus. First, the Gallery is a tiny part of the University, and admirably run on the smell of an oily rag. Second, if that logic was applied across the board, no one working anywhere in any major university would be able to say anything that offended any taxpayer—universities couldn’t function.

Of course, the irony is that media coverage has given the work far more exposure and status than it would ever have enjoyed in the Gallery alone. Plus, I suspect, far from being genuinely injured, the plaintiffs are revelling in the spotlight opportunity that this engineered controversy has afforded them—milking it for more than it’s worth. Meanwhile, to the art world, it’s a yawn. We had the blasphemy debate in the early 1990s. The work itself is now almost forty years old and Davila part of art history.

But, putting all that aside, I don’t see how the work is even anti-Christian. What do the critics think it means? In The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion, published two years before Davila painted Holy Family, Leo Steinberg drew attention to the frequency with which old masters once depicted Christ’s genitals. This highlighted the incarnation, the core Christian doctrine that Christ was God made flesh, made man, with all that entails—sexuality included. Artists deliberately exposed Christ to affirm his connection with humankind, with us all. Reiterated and monstrously exaggerated by Davila, this idea is surely the crux of Christianity, not a threat to it—even if Davila is out to offend.

•