.

A few months back, sojourning in New York, I was reading rave reviews of The Rhonda Lieberman Reader. I scoured the bookshops for a copy—to no avail. Amazon didn’t list it either. Frustrated, on my return to Wellington I contacted its boutique publisher, Pep Talks, directly. My copy has just arrived. Joy.

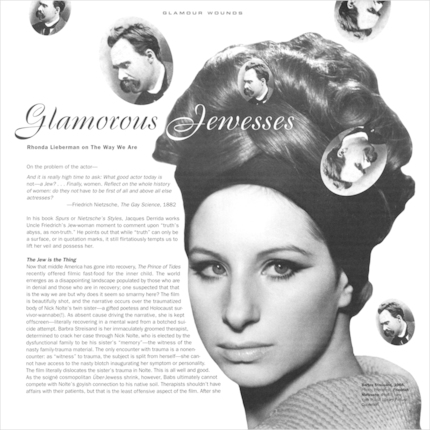

In the 1990s, I had the biggest reader crush on Lieberman. When Artforum arrived each month, her Glamour Wounds column was the first thing I’d read. Perhaps annoyingly, I’d read it aloud to my co-workers—some of whom appreciated my guilty pleasure.

Lieberman wrote sharp art pieces—her essay, ‘The Loser Thing’, brilliantly mapped the emerging abject Zeitgeist in American art. But, her Glamour Wounds columns were mostly about other stuff: Barbie and Barbra Streisand, Sandra Bernhard and Thomas Bernhard, Roseanne Barr and Coco Chanel, being a model for a day and teaching in Sweden, Miami’s Fontainebleu Hotel and grunge. Each revealed a new vector of personal interest, pleasure, and pain, triangulating her. Reading her, I thought I knew her.

Lieberman was Ivy-League educated, bookish but bratty, chatty, catty, and altogether ‘too Jewish’. She missed no opportunity to drop Yiddish slang. Her self-deprecating anecdotes invited sympathy, but her off-the-cuff observations had cruel cut through. She was a breath of fresh air. I wanted to write like that, even if it wasn’t me.

Here’s my favourite bit from ‘The Coldest Profession’: ‘Since I daylight as a pedagogue, getting into heavy textual discussions with any schmendrick who can get into a seminar, my ethical high road has more than a slight odor of the world’s oldest profession. I greet often clumsy advances responsively, indulge freakish trains of thought with the poker face of a hardened pro, shamelessly encourage the boring, and treat half-baked gibberish as if it were a cogent point, saving the client’s face by making him seem sentient and desirable before the group … The distinction between prostitute and professor is finer than we suspect.’

Glamour Wounds felt purposefully out of place in Artforum. But, while the column was unique, it was also timely. Published between 1992 and 1995—years that bracketed the 1993 Whitney Biennale—it resonated against the rise of identity politics. That moment favoured the worthy, personal testimony of marginalised Others. But how could you get a look in if you’re privileged—not invited to the pity party? Lieberman’s solution: join them anyway. Recast your privilege as pain, your subcultural passion as cultural oppression, and your singularity as marginality. ‘Glamour Wounds’ said it all.

Happily, I got to meet Lieberman. On a trip to New York—in late 1994, I think—I looked her up. She suggested a drink at the Algonquin Hotel, so we could sit in the room where Dorothy Parker and the Vicious Circle once held court. There, I felt at home, a million miles from home.

Later, after I returned to wet, dismal Dunedin, the highlight of my year would be the interruption of a Gallery staff meeting: ‘Robert, telephone. It’s Rhonda Lieberman.’ I felt like Cinderella, surrounded by ugly sisters, being handed my glass slipper. The reason for her call? She was concocting an identity-politics-mocking assignment for her Swedish art-school students, prompting them to address a cliched export property perennially used to characterise their country—Ingmar Bergman. ‘Is there a New Zealand equivalent?’, she asked. Is there what.

The Rhonda Lieberman Reader, ed. Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer (Los Angeles: Pep Talk, 2018). Order here.

•