.

I’ve just been on a mini-break to Melbourne, where my art highlight was Patrick Pound’s show, The Great Exhibition, at the National Gallery of Victoria Australia. Pound is a New Zealander, but he’s been based in Australia since 1989. His art has developed out of his activity as a collector. For decades, he’s been working away quietly, steadily, somewhat under the radar. In 2013, he presented a brilliant project, The Gallery of Air, in the NGV show Melbourne Now. He packed a room with hundreds of exhibits, drawn both from his quirky personal collection and from the NGV’s more well appointed and elite one. Each thing had something to do with air. Pound scrambled the cheap with the chic, the obvious with the occult, the venerable with the vulgar. Or, as he explained it, the display went ‘from a draft excluder to an asthma inhaler; from a battery-powered “breathing” dog to an old bicycle pump; from a Jacobean air stem glass to a Salvador Dalí ashtray made for Air India; from a John Constable cloud study to a Goya print of a farting figure’. Pound had his way with the NGV’s treasures, while pulling them down to the level of his own modestly acquired trophies, making them somehow equal, all just tokens in his game. The project managed to be, at once, super smart and a carnivalesque crowdpleaser. Perhaps that’s why they invited him back, to expand on the idea.

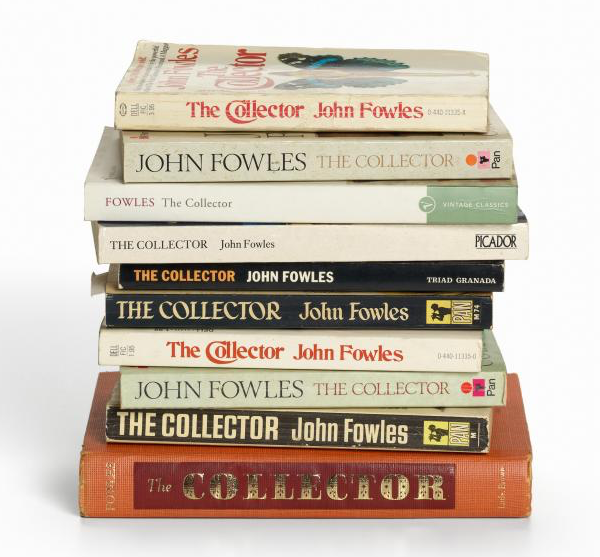

The Great Exhibition is an epic show. It fills all of the NGVA’s ground-floor galleries—and they’re jam packed. Again, Pound scrambles his collections with the NGV’s. Again, the show builds on his artist-collector-curator sensibility—that is, perhaps, its ultimate subject. Pound collects vernacular photos: there are displays of photos of photographers’s shadows, of people holding cameras, of reflections, etc. Riffing on Borges’s Chinese encyclopaedia, Pound is forever categorical. Sometimes the commonalities are crystal clear, sometimes elusive. There are gatherings concerning holes, falling, and ‘there/not there’. There are collections showing people sleeping and showing people with their backs turned. There are collections of pairs, of brown things, and of French things featuring the word ‘choses’ (the French word for things). Some sets allegorise Pound’s enterprise overall. For instance, he displays his collection of different editions of John Fowles’s novel The Collector. The Great Exhibition manages to be both epic and trivial. It suggests a set of Pinterest boards or Google image searches. Indeed, Pound made great use of the Internet to assemble his collections.

As a curator, I couldn’t help but ponder the way the show addressed my own vocation and its distorting effects. I felt pangs of pleasure and of guilt as Pound foregrounded the curatorial bag of tricks, flaunting the ways my colleagues and I place things into contrived contexts, fetishising some properties while forcing others to take a back seat, making things dance to our own tune. While artists legitimately fear being subsumed by wilful curators who have minds and projects of their own, Pound has turned the tables, making ‘the curator’ a trope for his art. (Patrick Pound, The Great Exhibition, National Gallery of Victoria Australia, Melbourne, until 30 July.)