.

I’ve just spent the weekend on art camp in New Plymouth, attending the opening of the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery’s ambitious new show Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph, curated by Geoff Batchen. My favourite work in it is Swiss artist Christian Marclay’s Allover (Rush, Barbara Streisand, Tina Turner, and Others) (2008). It’s a knockout.

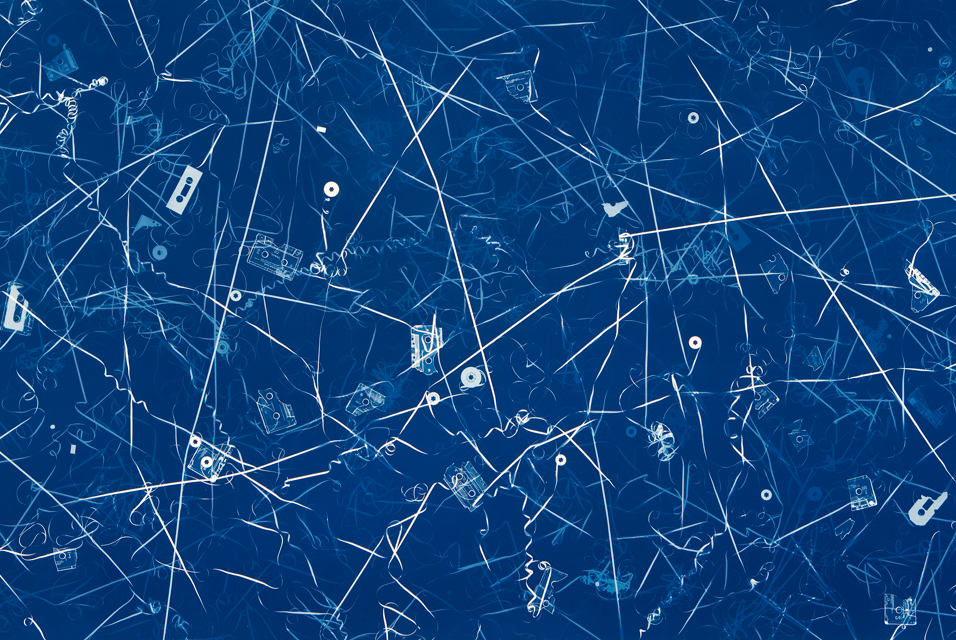

These days, some artists want to be ahead of the curve, negotiating the frontiers of new media, but many more are nostalgic for old media that are past their use-by dates. It has become a genre and the Marclay is a textbook example. He smashed-up audio cassettes—featuring music from Rush, Barbara Streisand, Tina Turner, and others—and spread fragments of their shells and lengths of their magnetic tape across a massive sheet of cyanotype photographic paper, exposed it to light, and developed it. Presto! The gesture piles redundancy upon redundancy, cross-referencing photography, music, and painting.

First, the work is a photogram and a cyanotype. The photogram is a primitive, cameraless form of photography and the cyanotype is an early type of photographic paper. Some of the earliest photos are cyanotypes, including photograms of botanical specimens and contact prints of drawings and graphics. The cyanotype survived, for a long time, as a means to reproduce architectural drawings (blueprints) and for proofing film for offset printing, but, today, it is little use to anyone.

Second, the ostensible subject—the audio cassette—is an obsolete analogue music format, redundant in this, our digital age. Landfill. Replacement value zero.

Third, the end result looks like an old Jackson Pollock action painting—it has that scale. Marclay links the Pollock idea—of ‘the brushstroke’ as a trace or record of the painter’s performance—with the way musical performances are recorded on tape. The work is paradoxical: Pollock was all about direct, unmediated expression (now a discredited, redundant idea), and yet Marclay foregrounds the detritus of mediation.

The now-retro recorded musics of Rush, Streisand, and Turner may be somehow registered here, but as ghosts—inaudible and indistinguishable. Marclay’s haunting, elegiac image suggests the streamers and rubbish left behind after a parade, reminding us that photography is a graveyard, the ultimate memorial medium. Go to New Plymouth, read it and weep. (Until 14 August.)