.

I recently found myself on a panel at Wellington’s Massey University, as part of their Art School of the Future symposium. Industry representatives were asked the question: What do your organisations want from art schools? I spoke for art museums:

.

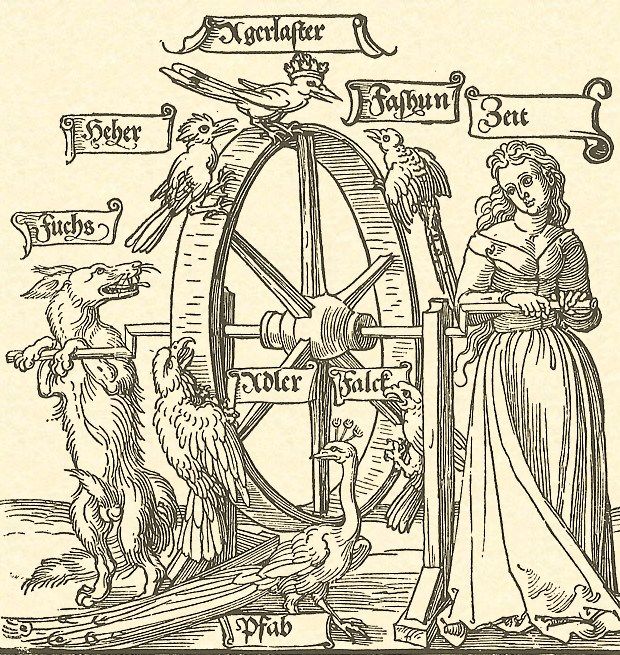

There are three big sectors or wheels in the art world: the market, the museums (in which I include alternative spaces, art criticism, public funding, etc), and the art schools. These wheels turn one another as well as themselves. Those of us in the market and museums sectors sometimes think we are the be-all and end-all, that art school is something you pass through on the way to the real world of the market and the museums. However, from the years I’ve been on the scene, I know this isn’t true. Art school never goes away—you can check out but you can never leave.

Although art schools are a big player, their influence on the other sectors can be piecemeal, masking the extent and nature of that influence. Art schools can be to the market and museums what dark matter is to the rest of the universe: pervasive, invisible, influential. As a curator, I am constantly interfacing with art schools and art-school culture, in different capacities, to different ends. I work with artists who teach and artists who study. I tap into art-school funding and residency programmes, I drop by to participate in art-school discussions, and art schools represent a key part of my audience.

The art world looks different depending on which sector you spend most of your time in. That determines who you talk to, in what order, and what language you speak. Each sector contains good and bad. There is a joyous, communal aspect to inter-sector and infra-sector interaction (‘the art life’), but there is also a bitter, agonistic one. Each sector wants things from the others; each wants to co-opt the others to its own ends, to turn them into enablers. And, each wants to safeguard itself from co-option, to not be made an enabler itself.

What do museums want from art schools? First, better art from students and staff. Not box-ticking, sausage-factory art. Not production-line expressions of art-school priorities and in-grown research-evaluation methodologies, approved by the ethics committee. Art that is audacious and transformative, that adds something, that changes the landscape. Second, bigger audiences, more art-school participation in what we are doing. Students and staff should be a larger and more regular part of the museum audience. Informed art-engaged audiences help us to raise the level of the discussion. (With regard to this, there is a good side to art schools having their own galleries, museums, seminar programs, residencies, publications, etc. It can facilitate engagement. But, it can also do the opposite, making art schools into gated communities—self-serving, self-sufficient, solipsistic; art worlds unto themselves, ultimately disengaged with the art world beyond. Too often, engagement is the argument, but isolation the reality. Art school becomes a wheel turning nothing but itself.) Third, capital. We want access to art-school energies, networks, resources, and, always, money—without strings attached, of course.

Museums want what’s good for museums. We want art schools to deliver flowers, pay for dinner, and open doors for us, but also to respect us when we say ‘no, not tonight, I have a headache’. In short, we want art schools to treat us as ends not means (while we happily treat them as means not ends). Love is a battlefield.