2004 Walters Prize (Auckland: Auckland Art Gallery, 2004).

Et Al.

In The Art of War, Sun Tsu advises, ‘All warfare is based on deception. Hence, when able to attack, we must seem unable; when using our forces, we must seem inactive; when we are near, we must make the enemy believe we are far away; when far away, we must make him believe we are near. Hold out baits to entice the enemy. Feign disorder.’ Et Al. have surely taken this principle to heart. The Auckland-based collective toys with viewers, persistently wrong-footing them. Theirs is an art of misdirection. For instance, Et Al. may engage in postmodern play with personae, persistently exhibiting under noms-de-plume and sidestepping interviewers, yet the work is astonishingly consistent, even signature in style and content. Et Al. may use conceptual-art formats and trowel on art references and philosophy citations, yet, perversely, beneath this, the work is almost expressionist—emphasising mood and sensibility. With Et Al., it’s always hard to know where to look, to distinguish what’s crucial from what’s contingent, signal from noise. It’s also hard to pinpoint the artists’ identifications. The work is full of references to things institutional, but it is never clear whether Et Al. are at war with the institution, conspiring with it, or both. For the uninitiated, this can be frustrating. But, for the Et Al. fan, it’s another matter. For the fan, the habitual perversity and ambivalence prove reassuring, because they are the constants that define the Et Al. universe. They’re normalised within the work’s regime. Et Al.’s installation Restricted Access exemplifies the approach. The group created it for their 2003 retrospective show Abnormal Mass Delusions? at New Plymouth’s Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. Painted institutional grey, the space looked less like a pristine exhibit and more like a grungy cellar or utilitarian lock-up. Cleaning out their dealers’ stockrooms, the artists piled up as much unsold work as they could muster, quantity proving more crucial than quality, then installed cyclone fencing in front of it, preventing us from getting a decent look. The resulting set suggested a workspace—amongst the stuff was a lamp-and-table-and-chair, awaiting the artist-attendant-caretaker. It also recalled Dr. Lecter’s cell, making us wonder whether that fence was there to protect the artist or the viewer. The work’s title, implying access and restriction at once—a contradiction-in-terms—contextualised the work’s refusal as tease, an exercise in simultaneously evading and accepting the invitation to be surveyed.

.

Jacqueline Fraser

Walter Benjamin famously remarked, ‘There is no document of civilisation which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.’ Jacqueline Fraser plays in the space between civil appearances and barbaric realities. Her hieratic tableaux are drawn and collaged directly onto the wall, typically with wire and fabric. In the 1990s, she introduced allegorical female characters into these scenes, their chic/facile lines recalling Warhol’s early fashion illustrations. Impeccably dressed, elegantly shod, and immaculately coiffured, Fraser’s heroines were incongruously stylish, especially when her works hinted at themes of mental illness, homelessness, and general disenfranchisement. It was as though Fraser’s pauper-princesses had risen above everyday inequities to achieve a certain sanctity, recalling those images of martyrs emanating grace even as defiled. But this reading got harder to sustain when Fraser followed up with a series of drawings of women’s shoes on squares of fine fabric, annotated with names of weapons—<<SURFACE TO AIR BATTERIES>>, <<ANTHRAX>>, <<12 GUAGE SHOTGUN>>; insults—<<YOU’RE A WASTE OF SPACE>>; and groovy militant slogans—<<UNCO-OPERATE BABY>>. Was Fraser offering fashionable female accessories as means of jihad, laughing at fashion’s pretense to be part of the cultural revolution, or just letting those questions hang? In her recent installation, <<Invisible>> (2004), Fraser seems to have completely turned on her former heroines, and is now indulging the flipside of her love/hate relation with them. Her installation mocks up a well-appointed palace-room with pink walls, sumptuous drapes, and chandeliers. On the walls, fashionable females teeter precariously on their stilettos, possibly in a trance; one floats horizontally, as though magically levitated. Instead of using her trademark wire outlines, Fraser drew her ciphers’ exposed faces, hands, and elegantly shod feet on acetate. Interchangeable, like mannequins, they are differentiated only by the treatment of their tailored Italian suits and by their accessories (fur hats and mask pulled over their eyes). Accompanying text panels juxtapose air-head ab-fab truisms—<<WE’RE LOOKING AT YOU. CIAO BELLA.>>, <<MY FUR COSSACK HAT ENHANCES MY LOOK.>>, <<NO ONE RECOGNISES ME WHEN I WEAR DARK GLASSES.>>–with brands of anti-depressants, painkillers, anti-psychotics … drugs that grant the smart set the perma-smiles to go with their perma-tans. One could only recall those headlines: ‘Donatella in Rehab!’ In this Dior hell, this vapid world of Tattler tribalism, Fraser’s svelte, sympathetic freedom fighters have turned into stylish vampires and victims and have crashed the art party; Fraser reframing la dolce vita as a drug-induced denial. Style, manners, and propriety have a floating status on Fraser’s work: sometimes they seem part of the problem, sometimes part of the solution. If the artist ultimately offers no real pointer either way, perhaps it’s because she agrees with that other dandy, Oscar Wilde, that ‘Consistency is the last refuge of the unimaginative.’ Hey, chic happens.

.

Ronnie van Hout

Ronnie van Hout’s work is underpinned by a play between comedy and tragedy, between self-abandon and introspection. Some time in the mid-1980s, the novel idea that originality is bunk gave him license to mimic canonical artists and fashionable strategies. If artists are typically cast as strong personalities, Van Hout seemed to offer the opposite: a weak personality open to suggestion. In one work, he even presented himself in a séance, as a medium through which others spoke. However, no matter how deeply Van Hout got lost, how much he ‘abandoned me’, his work always needed to be read in terms of his particular adventure, his negotiation of this landscape of others. In the 1990s, self-portraiture became more prominent in Van Hout’s work, the strain between self and others became more pronounced. Van Hout’s installations No Exit Part 1 and 2 (2003) pay homage to the 1944 play Huis Clos (No Exit) by French existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre. Sartre argued that other people necessarily recognise and objectify us, limiting our freedom and sovereignty. In his play, three dead people—cooped together for eternity—realise they are in their own personal hells. Van Hout’s past work would seem to challenge Sartre’s view, given that Van Hout is celebrated for finding personal release by camping out in the desires and identities of others. But things have become more complex. In No Exit Part 1, a Van Hout mannequin stands before a fireplace. He appears to enjoy mystic communion with birds-in-the-hand, like some contemporary Saint Francis, a long-haired hermit, a loner; we her the birds discussing his plight. Meanwhile, in an accompanying video, another Van Hout, in white overalls and alien mask, haunts a graveyard. The images are mismatched: one is genuinely spooky, the other something out of Ed Wood. Part 2 features the work I’m Not Trying. A Van Hout mannequin, this time nerdy, tracksuited, lies down on the job on the gallery floor, while a stuffed magpie bears witness. Close by, a small monitor set into a fake rock shows the same scene played out by the artist for real in the middle of a park. The title is spelt out in play-doh letters in front of a distorting mirror, allowing the viewer to take the place of the artist in his self-portrait. In an accompanying sculpture, casts of Van Hout’s head, fake logs and fake rocks stack up to spell out: ‘NO NO’. It’s like a demented Chris Booth sculpture, made in collaboration with the Dead Tree School and cannibals. This piece contains the most overt reference to Sartre’s play. An inset monitor finds Van Hout sitting on a couch with a monkey man (Monkey Madness) and a dog man (Sculp D. Dog) representing alter egos. Bored, the artist conducts a depressing monologue direct to camera, bemoaning his silent partners. In offering no dispute, no other angle, Van Hout’s companions offer him no help in perfecting his point of view. Do we count them as him or as others? Certainly, in furnishing no dispute, no other angle, they offer him no help in perfecting his point of view. Van Hout’s No Exit installations exemplify a Catch-22. Self and others many be in opposition, but they aren’t alternatives. We can’t really look to the other to escape the self, or vice versa. As Sartre would have it, ‘Hell is other people’, but only because these witnesses make us self-conscious.

.

Daniel von Sturmer

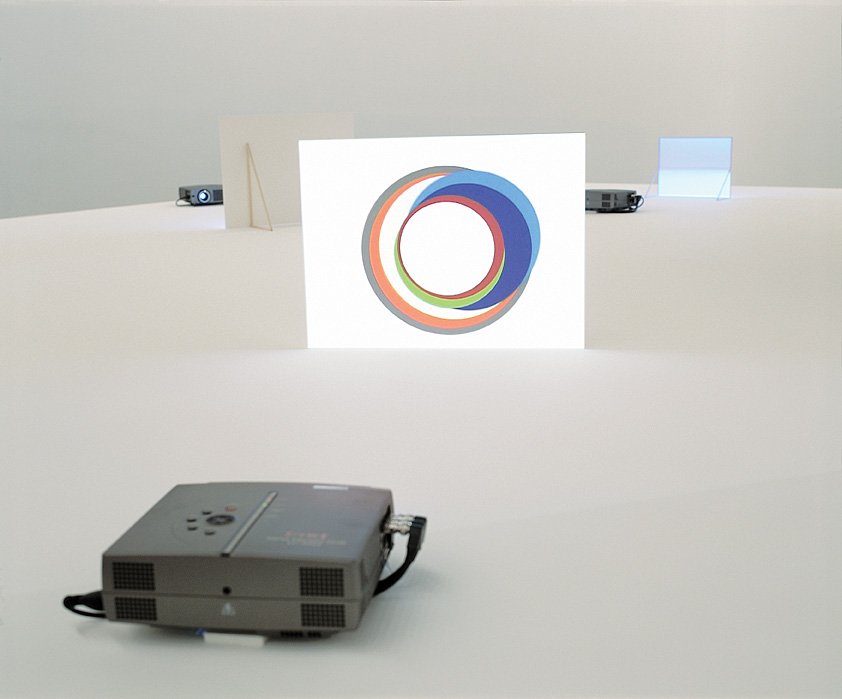

Asked to imagine an art gallery, many of us would instantly picture a classic ‘white cube’. As modern art’s preferred showcase, the pristine white-walled gallery has become a cliché. The principle was to strip away distractions, framing art off from the world, and yet the white cube has become a curiously loaded context, combining the sanctity of the church, the formality of the courtroom, and the mystique of the laboratory with chic design. Not content with simply allowing us to see the object in splendid isolation, the white cube now stands for Truth itself. It is also a site where the art object is utterly fetishised—granted a mystic vitality. Daniel von Sturmer’s work engages our complex relation to the white cube and the varieties of truth it entails. His video installation The Truth Effect (2003) has one foot in minimalist phenomenology, another in filmic sight gags and special effects. The action occurs on an expansive table, a tilted plane. Five video projectors front-project and back-project onto small screens. The videos are all set within a white box. Some of the actions appear to be like magic tricks (concealing), others like science demonstrations (revealing). Quotidian objects become comic characters: some springy and elastic, others dense and dumb. One video shows a paper cup, a cork sanding block, and a roll of sticky tape jockeying for position within the box. They move, decisively or sluggishly, perhaps under their own steam, perhaps drawn by hidden forces. We become embroiled in anticipating which thing will move next and how, based on its position, size, weight, and shape, and its relation to the others and the box. Of course, the effect is caused by rotating the box, slowly tumbling the objects, only we don’t see that at first because the camera’s position is fixed in relation to the box and there’s no outside reference point. In other videos, coloured circles of decreasing size are overlaid on a turntable, creating 3-D vortex effects, referencing Duchamp’s Rotoreliefs; a grey rectangle is held in front of the camera so it appears to become the wall or ceiling it obscures; and sticky tape rolls up an apparently inclined plane, miraculously coming to rest on the slope. Some of the videos ask us to reverse-engineer their effects, others let us in behind the scenes. The Truth Effect exploits a play between expectation and perception, between real space and pictorial space, between the wide world and the video frame. It doesn’t explore something we don’t know, so much as revel in a deft display of textbook paradoxes. The Truth Effect engages these paradoxes to explore and conjure with the rhetorics of art, science, and illusion.

.

[IMAGE: Daniel von Sturmer The Truth Effect 2003]