(with Stuart McKenzie) Sport, no. 4, Autumn 1990.

In 1936, Rita Angus travels by train 116 kilometres north-west of Christchurch, and sketches the railway station that she soon immortalises in the celebrated painting Cass. Half a century later, Julian Dashper makes a pilgrimage to the site where Angus exercised her miraculous vision. The photograph he takes of the station records a small first-aid box, marked with a cross. Although this cross is not depicted in Angus’s work, Dashper concentrates on the detail religiously, and proceeds to elaborate it in ten drawings. Inflated with humility, he can only allow himself the fragment Angus deemed unworthy to appear in her masterpiece. Or, if the cabinet wasn’t there originally, we might imagine that the pilgrim refuses himself the privilege of recreating the experience of the Mistress, and worships her only through the pathetic and belated detail. This act of denial attests his own station of the cross, and Dashper markets his passion in a deluxe edition of ten works, in which his photograph is accompanied by one of his original drawings.

The cross in the landscape is, of course, an obsessive subject for New Zealand art. McCahon used it throughout his career, Angus in her paintings of the defiled Bolton Street cemetery, Smither in the fourteen cross-shaped landscapes he dubbed The Rita Angus Series, and Peter Ireland in Fourteen Stations of the Cross and elsewhere. Apparently unwilling to step on the toes of his betters, Dashper deliberately stumbles into the canon.

.

Much of Julian Dashper’s recent work alludes both to New Zealand art history and to nasty design styles from the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. For example, in the Murals for a Contemporary House (1988), mock-modernist canvases, executed, according to Dashper, after McCahon’s French Bays, are hung over freestanding screens upholstered with a lurid 1970s fabric. The rumour that these works were informed by McCahon has received institutional endorsement through the inclusion of Mural for a Contemporary House No. 4 in the Auckland City Art Gallery’s 1989 exhibition After McCahon.

Francis Pound, never one to take a McCahon reference lying down, disputes this connection in his review of the show.1 Rather, he insists that this Dashper is indebted to Gordon Walters’s work of the 1950s. In the recent book on Walters, Order and Intuition, Pound continues to elaborate his thesis. Seeking to valorise the local modernist tradition of formal abstraction and grant its major practitioners their moment in the sun, Pound rejects the critical prejudice towards nationalist landscape exemplified, he insists, in the art-historical focus on McCahon. Creating an alternative tradition, he promotes a lineage extending from Walters through Killeen to Dashper. In this genealogy, the acknowledgement of his elders by the young man serves to vindicate parents and child. Accordingly, while applauding Dashper’s painting as an example of modernist abstraction, Pound does not attend to the way it is compromised and belittled by being hung on a tacky divide. In fact, Dashper’s Mural could be read as a parody of modernism or as an apotheosis of the vulgar and artless through its association with the pedigreed and artful.

Ironically, in conflating the elite and the derided, Dashper is once again taking advantage of a tradition endorsed by local art history. McCahon, according to legend, was inspired to use speech bubbles following a superb encounter with a Rinso packet. And Walters adapted Maori motifs at a time when Maori art was regarded as being of ethnographic interest only.

.

Dashper furthers his project of celebrating the trivial by his use of extravagant frames. In doing so he suggests that the work is merely bombastic, all frame and no content; or that the trivial is actually profound, irritating viewers to wonder if it is not, in fact, their own readings which are superficial.

In the After McCahon exhibition, Dashper borrowed the Gallery’s frame for McCahon’s Imprisonment and Reprieve (1978–9). This work on paper was made to be pinned directly to the wall. However, to prevent the laying on of hands, the Gallery has constructed a frame that can be hung over the work. McCahon’ s intention is thus both honoured and denied. The work is still pinned to the wall, but now contained. In his turn, Dashper used the frame to encompass five rather inconsequential works of his own, spaced out to fill the gap left by McCahon. It might seem that the gallery itself had chosen to enshrine Dashper’s works. Despite their scrappy quality, the frame insists that they are true art. In fact the guts of the work is the frame, and its contents an excuse to show it off. Not simply physical, the frame which Dashper usurps is ideological.

The offer to do an ‘artist’s choice’ show gave Dashper another opportunity to profit from the ideological frame of the Auckland City Art Gallery. Dashper contextualised a recent Dashper in a perverse line-up, which included adopted father figures Walters and Killeen; and also works by Robert Indiana, Theo Schoon, Lois White, Guido Reni, Merylyn Tweedie, and John Weeks. Weeks’s ‘head of a monkey’, a weak work by this important artist-teacher, was as out-of-place as Dashper’s own. But perhaps, by including the Weeks, Dashper was aping Picabia’s notorious ‘still life’ of 1920, which featured a stuffed toy monkey surrounded by the words ‘Portrait de Cezanne / Portrait de Renoir / Portrait de Rembrandt’. Like Picabia, Dashper establishes a canon in order to subvert it. Mr Dashper’s ‘bad show’, with its gratuitous selection, quirky hanging and obscure lighting, successfully demeans the work of more established artists, so that his own efforts might not seem exceptional. In this manner, Dashper celebrates himself as a big gun in the canon.

In flattering himself, Dashper also flatters the sophistication of those viewers pleased to detect his often blatantly obscure references. His selfpromotion is thus accepted and confirmed by those whose business is the artworld and its legends. Appropriately, he has the most prestigious dealers, Sue Crockford and Peter McLeavey, both of whose stables include Walters and Killeen. These dealer galleries are willingly served and exploited as frames. Regarded as holy sites, even their most inane features excite Dashper’s devotion. A stain on McLeavey’s carpet, Dashper proudly insists, inspired an entire exhibition.

.

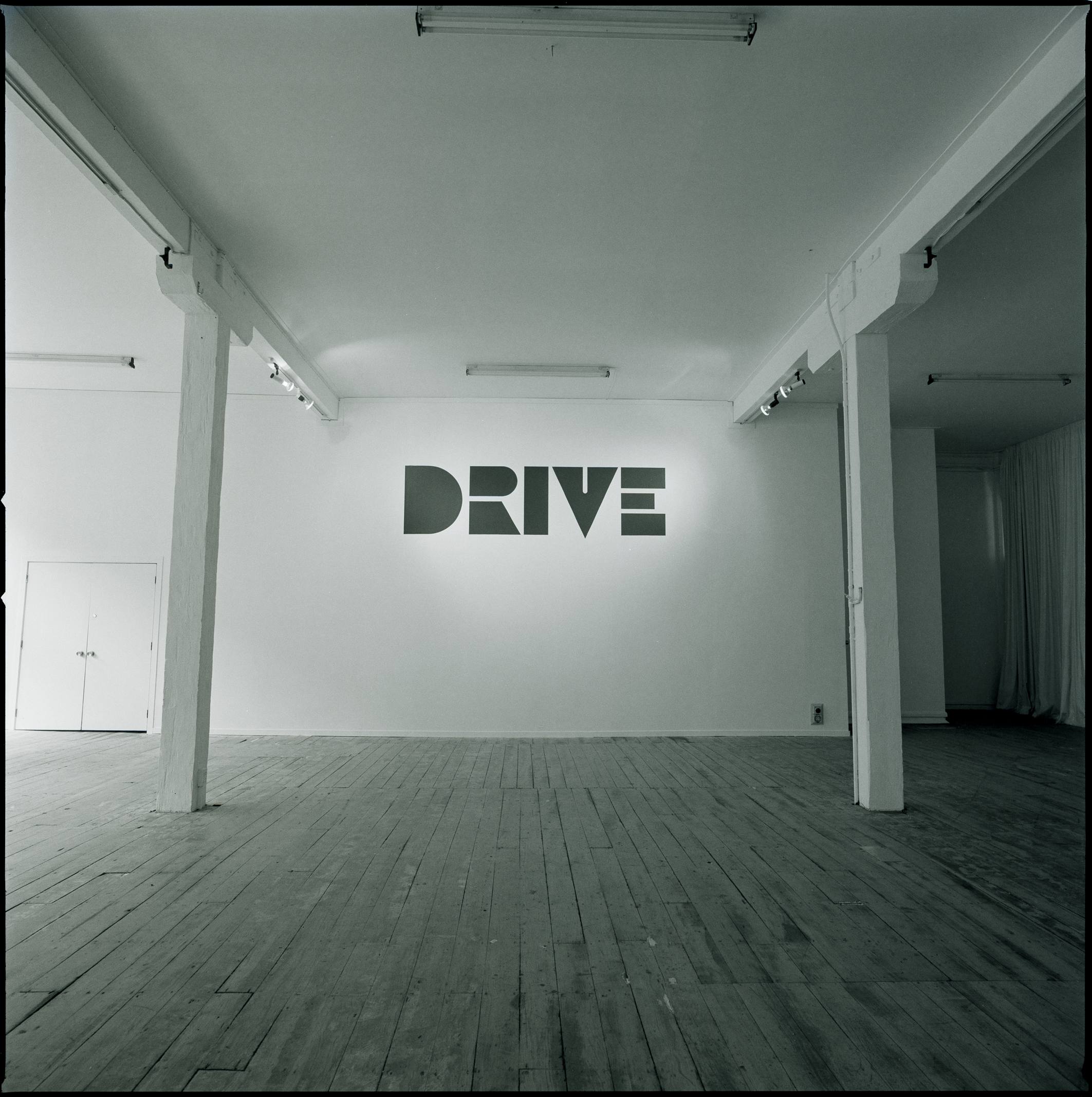

Modernist artists, such as Walters, sought to explore the physical supports of their works. Similarly, but inversely, Dashper seeks to advertise the support structure of his work, the structure of the artworld. While modernist works asked to be read in terms of internal references, Dashper’s work disappears into a host of external references. This process is clearly evidenced by Drive, Dashper’s installation for the Occupied Zone exhibition at Auckland’s Artspace (1989).

The other work in the Quay Street space was a sculptural installation by Judy Darragh. She chose a small annex, so Dashper grabbed the big room. Framed by the otherwise vacant white space, freshly painted by the artist, the few words which comprised the work appeared portentous. DRIVE was written big, in a gimmicky 1970s typeface, high up, in the centre of the main wall. The word was presented like some kind of altarpiece, to be approached reverentially. Yet such reverence seems ridiculous given the banality of the typeface and the crassness of the sentiment.

DRIVE could be a reference to Dashper’s much noted career as a taxi driver (other works draw on this biographeme). DRIVE, a brand of washing powder, is a smart reference to McCahon’s Rinso packet. And, of course, DRIVE also parades Dashper’s careerism.

On another wall we find ‘the label’, similarly sign-written: ‘Building. A type / Julian / Dashper’. The surname is reversed out of a black block. Around three edges of this block, the masking tape has been left on, as if the sign writer—the same man employed by Billy Apple—was still waiting for the paint to dry. But surely this tape is a reference to the legendary masking tape McCahon used in executing Here I Give Thanks to Mondrian and other works.

These references are simply references, simple references. They do not enlarge upon one another. The work has nothing to say about what it refers to, though this becomes a kind of comment in its own right. The references are oblique as well as obscure. It is not the works proper which are invoked, so much as the stories surrounding them. McCahon supposedly copied his speech bubble from a Rinso packet. Dashper quotes not a speech bubble, but another brand of washing powder. Dashper refers not to the aesthetic of Here I Give Thanks to Mondrian, but gets off on a technicality. He leaves the masking tape on as an allusion to what McCahon took off.

Dashper buys his imperial suit at the opportunity shop of art history. Transparent, his practice is nevertheless resolute. In the words of the New Testament, ‘he has built himself up through faith’.

.

Julian Dashper. Artist.

The meek will inherit the earth.

- Francis Pound, ‘In the Wake of McCahon: A Commentary on After McCahon’, Art New Zealand, no. 52, Spring 1989.