Nine Lives, ex. cat. (Auckland: Auckland Art Gallery, 2003).

Michael Stevenson’s career has had a bizarre trajectory. In the late 1980s, he was making folksy paintings of small-town bible-belt New Zealand: its church halls, stacked hymn books, and caravan parks—its glum evangelism. Today, he is a multi-media conceptual-art installation artist, living in Berlin, and representing New Zealand at the Venice Biennale. As much as his work has changed, something has remained constant: Stevenson’s insistent outsider point-of-view; his off-kilter, provincial perspective. Mimicry is at the heart of his practice, as subject and strategy.

Around 1993, Stevenson’s work took a major turn. Inspired by a trip to the US, he extended his subject matter from heartland New Zealand to frontier America. Fueled by background reading, Stevenson became a conspiracy theorist, illustrating bizarre connections between late-1960s American earth art and covert interests: big tobacco, the military, the Hells Angels, and DIA. Reproducing, by hand, classic documentary photographs of earthworks, he inserted odd details, to suggest things that may have been doctored out of the originals: Marlbro men invade a Serra, ‘Lynyrd Skynyrd’ is graffitied onto Heizer’s Double Negative, UFOs visit De Maria’s Lightning Field. Stevenson’s alternative account of the art world expands: hostages crawl across gallery floors using Judd boxes for cover, Nauman and Kosuth neons present right-wing political slogans. In some works, classic art images are reproduced with embedded crypto-fascist messages, only visible under black light. Rewiring his source images with paranoid links, masquerading as ‘what really happened’, Stevenson links contemporary art to other forms of extremism, exposing the heart of darkness behind art’s humanistic press release. His ultimate subject is provincialism: the way art is experienced on the peripheries, as a covert plot to insure our marginality. The work reflects Stevenson’s Pentecostal upbringing, where art was always suspected of being in bed with the devil.

Chris Chapman sees Stevenson as a voice in the wilderness, an antidote to postmodernism. He writes: ‘If postmodern thought sees power as a complex web of performance and discourse, the conspiracy theorist sees it as a straightforward series of covert acts. If postmodernism has abandoned linear historical narrative, the conspiracy theorist returns to a nation of direct, even mechanical causation. If postmodernism is skeptical of claims to truth, conspiracy theory clings to the fact that Truth (albeit the Awful Truth) can still be found beneath veils of dissimulation.’

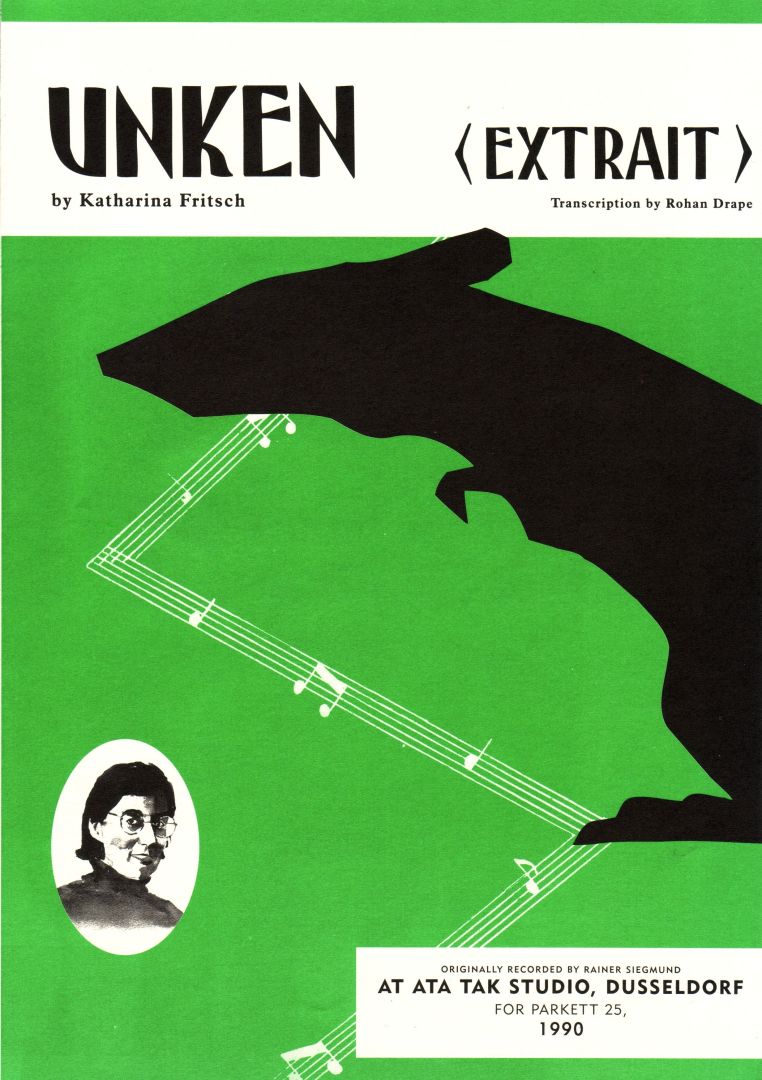

Moving to Melbourne in 1994, Stevenson met a like-mind. With Danius Kesminas he founded an on-going collaborative project. Slave Pianos has been described as ‘an organisation dedicated to the collection, analysis, performance, and recomposition of sound works by visual artists.’ ‘Music and works in sound by visual artists have been recomposed, arranged and transcribed for a range of new instrumentation, beginning with the piano.’ Slave Pianos first presented their cover versions entertainment-style, using a Playola, a mechanical piano player directly descended from the Pianola, which popularised the automatic playback of musical compositions in the 1920s. The repertoire ranged from New Zealand locals (like Daniel Malone, L. Budd, and Ronnie Van Hout) and 1980s Australian art stars (John Nixon and Peter Tyndall) to major world artists (Jean Tinguely, Louise Bourgeois, George Brecht, and Katharina Fritsch). Like obsessive fans who love but don’t understand their subject, Stevenson and Kesminas decontextualised, hollowed out, and transformed their sources in the process of their otherwise fastidious reconstructions. What had been spontaneous, intuitive, and against music perversely became jukebox fodder. If Fluxus artists attacked the piano as a symbol of bourgeois values and populism, Stevenson and Kesminas reinstated it, trumping the avant-garde.

The possibilities opened up in Slave Pianos informed Stevenson’s subsequent ‘archival projects’, which uncover bizarre links between art history and social history, between micro and macro-histories. Created for Berlin’s Kapinos Gallery in 2001, Call Me Immendorff tracks media response to German painter Jorg Immendorff’s 1987–8 Auckland artist’s residency against the concurrent stock market crash and the subsequent fall of the Berlin Wall. A suite of facsimile drawings meticulously reproduced sensational newspaper clippings about Immendorff’s visit, detailing his heavy partying and the death threat he received. Recreating the ensuing media circus, Stevenson’s expose addresses provincial misrecognition: New Zealand’s desire to experience an overseas art star is matched by Immendorff’s willingness to play along. Such archival projects involve another major move for Stevenson, from creating obvious fictions to exploring genuine historical realties. Another archival project, Can Dialectic Break Bricks?, for the 2002 Sydney Biennale, uncovered the role contemporary art played in the 1979 Iran Hostage Crisis. Truth is indeed stranger than fiction.

Stevenson is representing New Zealand at the Venice Biennale this year. This Is the Trekka centres on the New Zealand’s supposedly indigenous car, made in the late 1960s, early 1970s. While the Trekka was promoted as indigenous, its guts—the engine and chassis—were imported from communist Czechoslovakia. Suggesting at once a belated Eastern Block trade display and a deconstructed social history exhibit, This Is the Trekka probes economic, political, and cultural contradictions in Cold War New Zealand. Combining indexes and artifacts, restorations, reconstructions and representations, it plunges viewers into an oddly inflected interpretive space. In Venice, someone said, ‘It’s so provincial.’ Someone else said, ‘You, know, it’s a very European story.’ Both were right.

___

.

.

Robert Leonard interviews Michael Stevenson.

.

Michael Stevenson: It started in 1998. It was a collaboration with Danius Kesminas, who was also living in Melbourne. I’d worked with Danius before, but we both recognised that this was something different, something major. We had this idea of taking artists’ sound and music pieces, usually overtly avant-garde things, and presenting them using a Playola, a modern player-piano. Danius had already done things with music in pop/rock contexts, and he plays in Loin Groin, an Australian pub band. Danius knew Neil Kelley, a lecturer in the Music Department at La Trobe University. Neil and Rohan Drape, a student of his, they did all the transcribing, and subsequently arranged the material, at first for piano and later for other instruments. Slave Pianos was all framed up within an established ethnomusicology methodology. You know, people going out and making field recordings of Hungarian folk music or something, then transcribing them into standard Western music notation to study the structures. Slave Pianos follows that format quite closely, but, instead of it being Hungarian folk music, it’s contemporary artists’ sound and music works. That transcribing process has been held up as being transparent when it comes to documenting folk music, but, of course, it isn’t at all.

.

Robert Leonard: And you also show it all as sheet music.

.

Sheet music leaves room for how a composition can be performed. When I was a child, people still bought sheet music for pop songs. I remember, I liked the band Hogsnort Rupert. My mother went into Colliers Music in New Plymouth and bought their sheet music and played it on the piano for me for my birthday. With Slave Pianos, we wanted to reference that folksy populist practice too, the transition that happens when a recording made by a pop band is performed on a piano by your mother. Slave Piano has now taken a huge range of forms, including live presentations using singers, string quartets, brass bands, and a jazz ensemble. While it proceeded from the history of artists engaging with music and sound, Slave Pianos always had the potential to veer off in other directions. We’ve even talked about architecture. Slave Pianos sets up a lot of potential avenues of inquiry that Danius and I can pursue individually or together. It could go in almost any direction.

.

Did you care what the pieces sounded like?

.

Absolutely. We wanted to arrive at an end point that was musically interesting, not just process-driven. Neil and Rohan were especially interested in producing scores and performances that were musical in their own right.

.

The artists represented in the Slave Pianos repertoire are an odd mix. New Zealand artists who are obscure even in New Zealand are given equal billing alongside major international figures.

.

It is a regional canon, a provincial canon.

.

Some pieces are homages to friends, others hostile takeovers. John Nixon and Peter Tyndall wrote letters of complaint.

.

Like all my work, Slave Pianos is incredibly personality-based, though it probably doesn’t seem that way at first glance. For years I was involved in making representations of the art world. That involved copying known works by known artists—personalities. I wanted to generate subversive unacceptable readings of works that had been ring-fenced intellectually. The most basic simplistic response was, ‘Oh, so don’t you like Walter de Maria.’ That’s what I mean by ‘personality-based’.

.

What was Slave Pianos’ first manifestation?

.

It was in Kassel in 1999 as part of Toi Toi Toi. That’s the version Auckland Art Gallery and Chartwell own now. Danius also took the piece to Scotland for The Queen is Dead, a Scotland/Melbourne exchange exhibition, where it was played on a Yamaha disclavier, which we nicknamed The Bertrand Lavier. We didn’t anticipate the problem of polyphony, with striking many notes simultaneously, and at the opening the disclavier actually caught on fire. There was smoke pouring out of it. That was what inspired us to present a piano enveloped in theatrical smoke at China Art Objects in LA a little later.

.

There, you used a white piano.

.

Yes. It was LA, so we went with a white one. And above the piano we had a cross representing puppeteer’s handles hung from chains. It was painted like the Confederate flag. We like playing out all sorts of ideas that have been applied to the piano, here ‘ebony and ivory’. The Confederate flag implied enslavement. Danius and I were talking a lot about Robert Mapplethorpe and miscegenation at the time.

.

It seems like work you could only make outside of New Zealand.

.

That’s true I think. New Zealand art, like New Zealand generally, is very self-referential without being very self-conscious. It was only after I’d left New Zealand that I realised some aspects of New Zealand social history could be of interest to a wider international audience, but they are not usually the stories recognised within New Zealand. That thought lead to Call Me Immendorff (2001), which I made for Kapinos in Berlin.

.

How did the German audience take it?

.

Everybody knew Immendorff, but no one knew the story. In fact no one even knew he’d been to New Zealand. They came at it through their own history, their place in the world. Immendorff’s appearing in New Zealand in 1987 was part of a pattern. Just before the wall came down, German art was everywhere globally. In New Zealand, we expected German artists to be stars—it seemed natural. But many Germans were anxious about German art being out there in such a big brash conquering-the-world way. It was subsequently a huge embarrassment to the German art world. In the earlier 1990s many younger German artists definitely did not identify with that kind of behaviour and kept their distance from painting. They were involved in critical practices, often in collaborative and collective initiatives using marginalised media. That really informed Call Me Immendorff’s reception in Germany.

.

So, was it read differently in Auckland in the Walters Prize?

.

It was understood as a local story in both places. In Germany, the work was about Germany; in New Zealand, it was about New Zealand. But in both places, it was about the media.

.

One of the new pieces you made for the Auckland showing was Hotel Bill (2002), a facsimile of Immendorff’s hotel bill, with its endless room-service charges, okayed by the gallery. I’m interested in what it means to hang that on the wall in a gallery where local artists were once paid for talks with book tokens.

.

Hotel Bill is really telling. It speaks volumes about New Zealand’s isolation, our aspirations to be involved in international art, and what we were prepared to pay to achieve that. It shows New Zealand placing itself in an international context in a very limiting way. It looks like internationalism, but it’s really provincialism in reverse. And it’s not dissimilar to the way we bring out an older established European name-curator like Harald Szeemann to judge the Walters, or how we tackle Venice.

.

You are in Venice right now, representing New Zealand with This Is the Trekka (2003). Why did you think the Trekka would be interesting to people overseas when it hadn’t been interesting to people in New Zealand?

.

With the Trekka, I could play on other ideas about New Zealand already in the European imagination. As far as the Cold War period was concerned, a couple of things were key: New Zealand as a survivalist haven, a place escape to, and its enormous agricultural production. The Trekka could focus a provincial South Pacific twist on the whole Cold War story, in the shadow of a bomb, French testing, whatever. Potentially this was a very interesting story for a European audience. I did the show like some old Motokov trade display. But the relationship between the objects was confused. It was important it remained like that, without any extra labelling. It was up to the viewer to imagine how these things could relate together.

.

You were at the Venice Biennale the time before last. How did your experience of the way that New Zealand presented itself then inform what you did?

.

New Zealand obviously has a lot of problems in Venice. When we finally decided to go, it had been running for almost a century, so we had a lot of catch-up to do. New Zealand still feels close to countries like Australia, Britain, and America. We still look to them for cues, for information. That would psychologically place us in the Giardini. But New Zealand arrives late and the door is barred, the gate is locked. So we end up off-site, more remote than Croatia. The Trekka is a metaphor for this condition. In the mid-1960s, we were going to build cars and be a first world nation. But when we did we actually got involved with countries like Czechoslovakia. And when we exported Trekkas, it was to Indonesia. And then the Pakistanis and Zambians got interested. And that’s very much the Venice story for New Zealand. It was great to do a project that had the capacity to engage with all those things. It was also a big change for me. Over the last ten years, my work has directly engaged with the art world. The Trekka project is more devolved; it’s like the telescope around the other way. I replaced the artworld-as-subject with the Trekka, but the work has implications for the artworld and beyond. A metaphorical reading of it can map New Zealand’s general aspirations then onto our art scene’s aspirations today. David Craig coined the term ‘Neo-Trekkaism’.

.

By putting the CNZ Desk in the show, you incorporated Creative New Zealand into your show, rather than being framed by them. The attendants sat behind it and it was covered in Creative New Zealand pamphlets.

.

I made the desk like some relic from an Eastern Block trade fair. It had that quote from W.B. Sutch behind it. Along with everything else, he was chairman of the arts council in the early 1970s. I wanted to link Sutch’s thinking to the current wisdom. The way CNZ used the table for their promotional material was serrendipity. It wasn’t designed for that, but I didn’t have the heart to tell them to remove anything. They were doing what they were going to do anyway. It was kind of perfect.